Some time after David has placed the ark in Jerusalem, a palace has been built for him, and he has a period of rest from his enemies, he decides that he should build a temple to house the ark (God’s home on earth). David communicates his plans to Nathan, the prophet, and Nathan affirms his plans. However, that night Nathan hears from God about His plans for David, and they are not at all what Nathan expects!

Some time after David has placed the ark in Jerusalem, a palace has been built for him, and he has a period of rest from his enemies, he decides that he should build a temple to house the ark (God’s home on earth). David communicates his plans to Nathan, the prophet, and Nathan affirms his plans. However, that night Nathan hears from God about His plans for David, and they are not at all what Nathan expects!

The verses that follow contain some of the most important words in the entire Old Testament because they capture God’s promises to David. These promises are often referred to as the Davidic Covenant. The New Testament writers believed that the promises made to David in 2 Samuel 7 were fulfilled in Jesus Christ. In order to understand who Jesus thought He was and who His disciples thought he was, it is imperative to understand the Davidic Covenant.

In verses 5-7, God reminds Nathan that He has never requested that a permanent structure be built to house the ark. God has been content to travel with His people, Israel, wherever they have gone.

In verses 8-9, God reminds Nathan that it was God who took David from being a simple shepherd to ruler over Israel. It is God who has given David all of his military victories. The second half of verse 9 begins the Davidic Covenant, the promises God makes to David and his descendants.

First, God promises that He will make David’s “name great, like the names of the greatest men of the earth.” Second, God promises that He will give Israel the land He promised them, and give them peace from their enemies.

Third, God will build a house for David, not the other way around. What follows are the key verses of the Davidic Covenant:

“When your days are over and you rest with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring to succeed you, who will come from your own body, and I will establish his kingdom. He is the one who will build a house for my Name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. I will be his father, and he will be my son. When he does wrong, I will punish him with the rod of men, with floggings inflicted by men. But my love will never be taken away from him, as I took it away from Saul, whom I removed from before you. Your house and your kingdom will endure forever before me; your throne will be established forever.”

These promises to David apply both to his son, Solomon, who would build the temple to house the ark, but also to all of David’s descendants. The greatest of David’s descendants would, of course, be Jesus Christ. Let’s look at each of the promises in order.

First, David’s house would not end with his death. God promises to “raise up” David’s offspring to succeed him. In fact, we learn that it is David’s son who will build a house for God. This promise is fulfilled in one sense when David’s son, Solomon, builds the temple between 966 and 959 BC. But in another sense, this promise must apply to another of David’s descendants, because Solomon’s throne is not established forever.

Second, the future descendants of David who rule Israel will be God’s sons. As the father of David’s descendants, He will manifest His love in two ways. First, He will discipline them when they sin by allowing their enemies to inflict harm on them. Second, even though they sin, His love will never be taken away from them. He will always love the descendants of David, regardless of their behavior.

Third, David’s house would endure forever. Time will not change God’s plans to establish the house of David.

How do these promises to David apply to Jesus Christ? According to Robert Bergen in 1, 2 Samuel: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture (The New American Commentary),

The divine declarations proclaimed here through the prophet Nathan are foundational for seven major New Testament teachings about Jesus: that he is (1) the son of David (cf. Matt 1:1; Acts 13:22–23; Rom 1:3; 2 Tim 2:8; Rev 22:16, etc.); (2) one who would rise from the dead (cf. Acts 2:30; 13:23); (3) the builder of the house for God (cf. John 2:19–22; Heb 3:3–4, etc.); (4) the possessor of a throne (cf. Heb 1:8; Rev 3:21, etc.); (5) the possessor of an eternal kingdom (cf. 1 Cor 15:24–25; Eph 5:5; Heb 1:8; 2 Pet 1:11, etc.); (6) the son of God (cf. Mark 1:1; John 20:31; Acts 9:20; Heb 4:14; Rev 2:18, etc.); and (7) the product of an immaculate conception, since he had God as his father (cf. Luke 1:32–35).

In verses 18-29, we read David’s response. He goes into the tent containing the ark and sits down and prays to God. David praises God from verses 18-24 and he petitions God from verses 25-29.

During his praise, David marvels over the fact that God has blessed him thus far, and then is further amazed that God has made this promise to establish his throne forever. David knows that God’s promises to David are a means to accomplish God’s will both for Israel and for all mankind. Remember that God’s original covenant with Abraham, upon which the Davidic Covenant is built, promised to bless the entire world through the descendants of Abraham.

David continues by proclaiming that God is one of a kind, that there is no other god except for Him. Likewise, the people of Israel are one of a kind because God chose them as the nation He would redeem. Their redemption demonstrated to all the people of the earth who God is.

In David’s petition to God, David boldly requests that God keep these promises He has made. David asks that God truly establish his house forever. Dale Ralph Davis, in 2 Samuel: Out of Every Adversity (Focus on the Bible Commentaries), notes that David provides an example for us:

Here then is still the major task for prayer today: to take God’s promises and pray he will bring them to pass. We must, of course, be certain any promise is a promise that rightly applies to us. Certainly David’s promise does. For this is the promise we ask God to fulfill every time we pray that God’s name will be held sacred throughout the earth (see v. 26; cf. Ezek. 36:20–23), when we ask for God’s kingdom to come and his will to be done on earth. The final King of David’s dynasty has come, yet his kingship must yet be fully, publicly, and universally displayed. But since the promises are reliable (v. 28a: ‘And now, Lord Yahweh, you are the One who is God, and your words will prove true’) the petition is sure to be granted.

We are to pray that God will bring His promises to pass and we can be sure that our prayers will be granted.

Following the death of Saul in 1 Sam 31 (around 1010 BC), David is anointed king over the tribe of Judah. The other tribes, however, give their fealty to Saul’s remaining son, Ish-Bosheth. This is the situation for 7 years, until Ish-Bosheth is killed by two assassins. It is important to note that David has nothing to do with the assassination and he, in fact, has the assassins executed for their deed.

Following the death of Saul in 1 Sam 31 (around 1010 BC), David is anointed king over the tribe of Judah. The other tribes, however, give their fealty to Saul’s remaining son, Ish-Bosheth. This is the situation for 7 years, until Ish-Bosheth is killed by two assassins. It is important to note that David has nothing to do with the assassination and he, in fact, has the assassins executed for their deed. During the time covered in 1 Samuel 18-29, David built up a small army of 600 men from the outcasts of Israel, while Saul continued to hunt David down in order to kill him. When we finally get to chapters 30-31, David and Saul are both facing armed conflicts, but with separate enemies. The narrator places these conflicts one after another to contrast how different Saul and David, with respect to their relationships with God, truly are.

During the time covered in 1 Samuel 18-29, David built up a small army of 600 men from the outcasts of Israel, while Saul continued to hunt David down in order to kill him. When we finally get to chapters 30-31, David and Saul are both facing armed conflicts, but with separate enemies. The narrator places these conflicts one after another to contrast how different Saul and David, with respect to their relationships with God, truly are. The events of chapter 17 occur several years after David is invited to stay at King Saul’s residence. It appears that at some point, Saul’s condition must have improved and David was allowed to go back and help his father with his sheep.

The events of chapter 17 occur several years after David is invited to stay at King Saul’s residence. It appears that at some point, Saul’s condition must have improved and David was allowed to go back and help his father with his sheep. Between chapters 8 and 15 in 1 Samuel, Israel has received the king she requested in the person of Saul. From the beginning, we know that Saul was not a man “after God’s heart” and although Saul has some military successes against Israel’s enemies, especially the Philistines, his disobedience of God’s commands would eventually cause him to lose his kingship.

Between chapters 8 and 15 in 1 Samuel, Israel has received the king she requested in the person of Saul. From the beginning, we know that Saul was not a man “after God’s heart” and although Saul has some military successes against Israel’s enemies, especially the Philistines, his disobedience of God’s commands would eventually cause him to lose his kingship. First and 2 Samuel were originally a single work that was separated into two books centuries after composition. These books continue the historical narrative where Judges and Ruth end. Since the books of 1 and 2 Samuel cover a period in Israel’s history of about 150 years (1120 to 970 BC), it seems that several sources were used to put together the books in their final form. Scholars aren’t sure when 1 and 2 Samuel were finally composed, but a date between 800 and 700 BC seems likely.

First and 2 Samuel were originally a single work that was separated into two books centuries after composition. These books continue the historical narrative where Judges and Ruth end. Since the books of 1 and 2 Samuel cover a period in Israel’s history of about 150 years (1120 to 970 BC), it seems that several sources were used to put together the books in their final form. Scholars aren’t sure when 1 and 2 Samuel were finally composed, but a date between 800 and 700 BC seems likely. The Book of Ruth is placed right after Judges in the Christian Old Testament, as part of the Historical Books section. As with most other books in the OT, the author is not known for sure, although Jewish and Christian tradition point to the prophet Samuel. If it was Samuel, it would have been written before the year 1000 BC, which is about the latest date for Samuel’s death.

The Book of Ruth is placed right after Judges in the Christian Old Testament, as part of the Historical Books section. As with most other books in the OT, the author is not known for sure, although Jewish and Christian tradition point to the prophet Samuel. If it was Samuel, it would have been written before the year 1000 BC, which is about the latest date for Samuel’s death. Toward the end of the period of the judges lived one of the most famous judges, Samson. He lived from approximately 1089 BC to 1049 BC. The story of Samson begins in chapter 13, which is where we pick up the narrative.

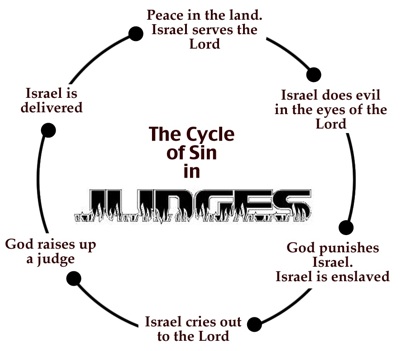

Toward the end of the period of the judges lived one of the most famous judges, Samson. He lived from approximately 1089 BC to 1049 BC. The story of Samson begins in chapter 13, which is where we pick up the narrative. The Book of Judges continues the historical narrative where Joshua ended. The author of Judges is unknown, although Jewish tradition ascribes authorship to the prophet Samuel. Samuel may have written portions of the book, but there were likely later editors that compiled it into its final form. Scholars date the final composition of Judges from some time between 700 and 1000 BC.

The Book of Judges continues the historical narrative where Joshua ended. The author of Judges is unknown, although Jewish tradition ascribes authorship to the prophet Samuel. Samuel may have written portions of the book, but there were likely later editors that compiled it into its final form. Scholars date the final composition of Judges from some time between 700 and 1000 BC.