In chapter 3, the Israelites are finally ready to enter the Promised Land, but to get there, they have to cross a river, the Jordan River. Given that there were tens of thousands of Israelites, young and old, along with all of their supplies, how would they do this? The Jordan River was not a small stream that could easily be crossed. Dale Ralph Davis, in Joshua: No Falling Words (Focus on the Bible)

In chapter 3, the Israelites are finally ready to enter the Promised Land, but to get there, they have to cross a river, the Jordan River. Given that there were tens of thousands of Israelites, young and old, along with all of their supplies, how would they do this? The Jordan River was not a small stream that could easily be crossed. Dale Ralph Davis, in Joshua: No Falling Words (Focus on the Bible), describes the scene:

The actual Jordan Valley between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea varies in breadth from 3 to 14 miles. Within this valley is the river’s floodplain, which is 200 yards to 1 mile wide. The floodplain was packed with tangled bush and jungle growth. . . . Then there was the river channel itself, which—if similar to nineteenth-century (AD) conditions—was from 90 to 100 feet broad, with a depth of 3 feet at some fords to as much as 10 to 12 feet. The current was strong because of the drop in elevation (a drop of 40 feet per mile near the Sea of Galilee and an average of 9 feet per mile overall). This means that the river Israel faced that springtime was no placid stream but a raging torrent, probably a mile wide and covering a mass of tangled brush and jungle growth.

Only a miracle from God will get the nation into Canaan. God’s instructions to Joshua are simple. Tell the people to prepare themselves. Send the Levite priests out first, carrying the Ark of the Covenant. The people are to stay back 1000 yards and watch the miracle. When the priests, carrying the ark, step foot in the water, the water will stop flowing. The people will cross the river on dry ground while the priests stand in the middle of the river with the ark.

And this is exactly what occurred. See verses 15-17 below:

Now the Jordan is at flood stage all during harvest. Yet as soon as the priests who carried the ark reached the Jordan and their feet touched the water’s edge, the water from upstream stopped flowing. It piled up in a heap a great distance away, at a town called Adam in the vicinity of Zarethan, while the water flowing down to the Sea of the Arabah (the Salt Sea) was completely cut off. So the people crossed over opposite Jericho. The priests who carried the ark of the covenant of the LORD stood firm on dry ground in the middle of the Jordan, while all Israel passed by until the whole nation had completed the crossing on dry ground.

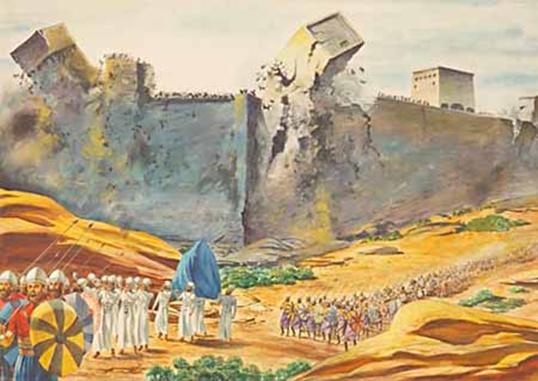

Now that the Israelites have crossed the Jordan, they must conquer the city of Jericho, and this is where the story picks up in chapter 6. How would Israel defeat a heavily fortified city with thick outer walls? God would provide a way. Here are his instructions to Joshua in verses 3-5:

March around the city once with all the armed men. Do this for six days. Have seven priests carry trumpets of rams’ horns in front of the ark. On the seventh day, march around the city seven times, with the priests blowing the trumpets. When you hear them sound a long blast on the trumpets, have all the people give a loud shout; then the wall of the city will collapse and the people will go up, every man straight in.

Notice that the ark would lead the way around the city. The ark represented God’s presence among the people, so the clear message to Israel, and to us, is that God gets the glory! He enabled Israel to enter the city. Joshua and his army could have never conquered Jericho on their own.

Verses 8-20 describe, in detail, the Israelites following Joshua’s orders exactly as commanded. Once the city walls fell, Joshua gave further instructions. They were to destroy all of the people and livestock within the city, and they were to remove any valuable items, objects made of gold, silver, bronze, or iron, and place them into the treasury of the Lord. The people were not to take any valuables for themselves. God warns them that if they take any valuables for themselves, they will be destroyed just as the people of Jericho.

Everything in the city was to be dedicated to God. Dedication, in the context of the conquest of the Promised Land, means either total destruction or donation to the treasury of God. The people of Israel were not to benefit from the destruction of Jericho, for they were serving as God’s instrument of justice.

Before we finish chapter 6, let’s review why God is giving Canaan to Israel. Is it because they are deserving of the land? Because they are a righteous people who are morally superior to all other nations of the world? No. Deuteronomy 9:1-6 gives the rationale for God driving out the Canaanites and giving the land to Israel: the sinfulness and wickedness of the Canaanites (their sins are catalogued in Leviticus 18:1-20:27). God was judging the Canaanites with Israel. That is why every bit of Canaanite culture needed to be destroyed.

The only people in Jericho who believed in God, who trusted Him for their salvation, were Rahab and her family. They were rescued by the two spies and taken to safety outside the camp of Israel. Joshua then cursed the city and anyone who would try to rebuild it.

Finally, we see that “the LORD was with Joshua, and his fame spread throughout the land.” Thus the conquest of the Promised Land had begun.

Joshua is the first book following the Pentateuch and it begins the series of books in the OT that are called the Historical Books (Joshua – Esther). The author of Joshua is unknown, although large portions of the book appear to have been written by a person who experienced the events recorded in the book. Early Jewish tradition indicates that Joshua himself was the primary author of the book, although some sections were likely added by later editors. If we accept Joshua as the primary author, then the book was likely completed near the end of Joshua’s life, around 1375 BC.

Joshua is the first book following the Pentateuch and it begins the series of books in the OT that are called the Historical Books (Joshua – Esther). The author of Joshua is unknown, although large portions of the book appear to have been written by a person who experienced the events recorded in the book. Early Jewish tradition indicates that Joshua himself was the primary author of the book, although some sections were likely added by later editors. If we accept Joshua as the primary author, then the book was likely completed near the end of Joshua’s life, around 1375 BC..jpg) Through Job 37, Job has listened to three “friends” and Elihu speak to him about why he is suffering so badly. Job, in turn, has responded to each of them, declaring his innocence and demanding that God give him answers. Finally, in Job 38, Job gets his wish.

Through Job 37, Job has listened to three “friends” and Elihu speak to him about why he is suffering so badly. Job, in turn, has responded to each of them, declaring his innocence and demanding that God give him answers. Finally, in Job 38, Job gets his wish. Having finished the book of Deuteronomy, we now move to the book of Job. Although the events of Job cannot be easily dated, there is some consensus that they occurred during the period of the Patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob). Or, to put a wide range of dates on the events of Job, we can say that they probably occurred between 2000 – 1000 BC. Because we are unsure of the dating, we choose to place Job in between Deuteronomy and Joshua chronologically.

Having finished the book of Deuteronomy, we now move to the book of Job. Although the events of Job cannot be easily dated, there is some consensus that they occurred during the period of the Patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob). Or, to put a wide range of dates on the events of Job, we can say that they probably occurred between 2000 – 1000 BC. Because we are unsure of the dating, we choose to place Job in between Deuteronomy and Joshua chronologically. Moses’s speeches and admonitions to the Israelites are about to come to an end. Chapter 31 begins with Moses telling them that he is 120 years old, and thus he is no longer able to lead the people. In addition, God has commanded that Moses not cross into the Promised Land because of his sin at Meribah.

Moses’s speeches and admonitions to the Israelites are about to come to an end. Chapter 31 begins with Moses telling them that he is 120 years old, and thus he is no longer able to lead the people. In addition, God has commanded that Moses not cross into the Promised Land because of his sin at Meribah. The Israelites have traveled around the borders of Edom and have arrived in the land of Moab, across the Jordan River from the city of Jericho. As they traveled, they encountered two kings who attacked them: Sihon, king of the Amorites, and Og, king of Bashan. Both armies were completely defeated by the Israelites. Having captured the lands of these two kings, the Israelites settle in their territories.

The Israelites have traveled around the borders of Edom and have arrived in the land of Moab, across the Jordan River from the city of Jericho. As they traveled, they encountered two kings who attacked them: Sihon, king of the Amorites, and Og, king of Bashan. Both armies were completely defeated by the Israelites. Having captured the lands of these two kings, the Israelites settle in their territories. The narrative skips over the next 37 years of wandering in the wilderness to the beginning of the last year before the Israelites would enter the Promised Land. This is where chapter 20 picks up the story.

The narrative skips over the next 37 years of wandering in the wilderness to the beginning of the last year before the Israelites would enter the Promised Land. This is where chapter 20 picks up the story.