In chapters 7-12 in the book of Joshua, the Israelites, led by Joshua, conquer the cities of 31 kings (see the list in chapter 12). God, as promised, drove the Canaanites out ahead of the Israelites, and the Canaanites who stayed behind to defy Israel were easily defeated by Israel’s armies.

Once these 31 kings were defeated, God reminds Joshua that much land is still to be taken, but that it is time to allocate all of the land to the 12 tribes of Israel. Some of the land that will be allocated is already in the hands of Israel, but some of the land still needs to be cleared of Canaanites. Take a look at this map to see how the land was allocated to the 12 tribes in chapters 13-21.

After all the land has been assigned, we arrive at, arguably, the climax of the Book of Joshua. In chapter 21, verses 43-45, we read:

So the LORD gave Israel all the land he had sworn to give their forefathers, and they took possession of it and settled there. The LORD gave them rest on every side, just as he had sworn to their forefathers. Not one of their enemies withstood them; the LORD handed all their enemies over to them. Not one of all the LORD’s good promises to the house of Israel failed; every one was fulfilled.

Verse 43 summarizes chapters 13-21, verse 44 summarizes the victories of chapters 1-12, and verse 25 summarizes the entire book of Joshua. Even though there was more land to be taken, Israel now had a firm foothold in the Promised Land. All of the promises God made to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob had been fulfilled. The tiny nation of Israel was able to take possession of land occupied by nations far greater and far stronger than they. This would have been completely and utterly impossible without God doing the work!

We now pick up the narrative in chapter 23. Joshua, who is 110 years old, senses that he is close to death and makes preparation for his departure. He first summons the leaders of Israel and reminds them of everything God has done for them over the previous 30 years in verses 1-5. In addition, he reassures them that the land they have been allotted, but not yet possessed, will be given over to them by God, as He promised.

In verses 6-16, Joshua warns Israel to carefully follow the Law of Moses and not associate with the nations of people still living among them. Remember that the primary reason that Israel is dispossessing the Canaanite nations is that their cultures and religious systems are extremely depraved. They are characterized by incest, bestiality, child sacrifice, and ritualized prostitution, among other things. If Israel assimilates with these people, then they too will start to commit the same awful sins and they will “perish from this good land.”

How will they perish from the land? God Himself will punish them. “If you violate the covenant of the LORD your God, which he commanded you, and go and serve other gods and bow down to them, the LORD’s anger will burn against you, and you will quickly perish from the good land he has given you.”

Israel is not exempt from God’s justice. He has punished the Canaanites for their sin, and He will do exactly the same to Israel.

In chapter 24, Joshua again summons all of Israel to hear his final words to them. Joshua rehearses the entire redemptive history of Israel, starting with Abraham’s calling and continuing all the way up to the current day, where they have seen for themselves the fulfilment of God’s promises to them.

Having seen all that God has done for them, what should the people do? “Fear the Lord and serve Him with all faithfulness.” Joshua commands Israel to choose between the gods of Egypt, the gods of Canaan, or Yahweh. For Joshua, the choice is simple: “But as for me and my household, we will serve the LORD.”

The people of Israel respond to Joshua that they, too, will serve the LORD. Joshua doubts their allegiance to the LORD and reminds them again that God will destroy them if they turn to the gods of the Canaanites, but the people respond twice that “We will serve the Lord our God and obey him.” Joshua then renews the covenant between God and Israel at Shechem, setting up a large stone as a witness to the covenant. The stone would remind the people of the promises they made to God.

Chapter 24 closes with the deaths of Joshua and Eleazar. After 30 years of leading Israel, Joshua was buried in his allotted land. The author notes that “Israel served the LORD throughout the lifetime of Joshua and of the elders who outlived him and who had experienced everything the LORD had done for Israel.”

In chapter 3, the Israelites are finally ready to enter the Promised Land, but to get there, they have to cross a river, the Jordan River. Given that there were tens of thousands of Israelites, young and old, along with all of their supplies, how would they do this? The Jordan River was not a small stream that could easily be crossed. Dale Ralph Davis, in

In chapter 3, the Israelites are finally ready to enter the Promised Land, but to get there, they have to cross a river, the Jordan River. Given that there were tens of thousands of Israelites, young and old, along with all of their supplies, how would they do this? The Jordan River was not a small stream that could easily be crossed. Dale Ralph Davis, in  Joshua is the first book following the Pentateuch and it begins the series of books in the OT that are called the Historical Books (Joshua – Esther). The author of Joshua is unknown, although large portions of the book appear to have been written by a person who experienced the events recorded in the book. Early Jewish tradition indicates that Joshua himself was the primary author of the book, although some sections were likely added by later editors. If we accept Joshua as the primary author, then the book was likely completed near the end of Joshua’s life, around 1375 BC.

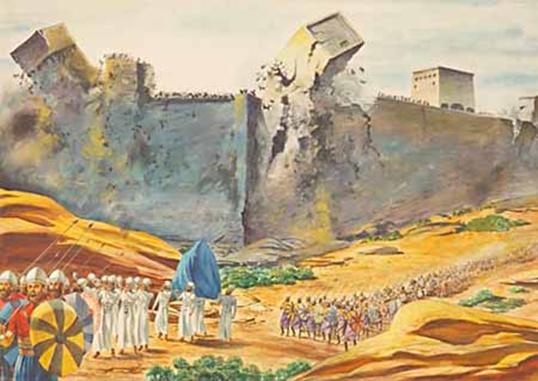

Joshua is the first book following the Pentateuch and it begins the series of books in the OT that are called the Historical Books (Joshua – Esther). The author of Joshua is unknown, although large portions of the book appear to have been written by a person who experienced the events recorded in the book. Early Jewish tradition indicates that Joshua himself was the primary author of the book, although some sections were likely added by later editors. If we accept Joshua as the primary author, then the book was likely completed near the end of Joshua’s life, around 1375 BC. Many Christians, as they read the book of Joshua, are uncomfortable with the accounts of conquest that are recorded there. The conquest of Jericho is the first in Canaan for the Israelites. The biblical writer describes the battle of Jericho this way in Josh. 6:20-21:

Many Christians, as they read the book of Joshua, are uncomfortable with the accounts of conquest that are recorded there. The conquest of Jericho is the first in Canaan for the Israelites. The biblical writer describes the battle of Jericho this way in Josh. 6:20-21: