The Book of Ruth is placed right after Judges in the Christian Old Testament, as part of the Historical Books section. As with most other books in the OT, the author is not known for sure, although Jewish and Christian tradition point to the prophet Samuel. If it was Samuel, it would have been written before the year 1000 BC, which is about the latest date for Samuel’s death.

The Book of Ruth is placed right after Judges in the Christian Old Testament, as part of the Historical Books section. As with most other books in the OT, the author is not known for sure, although Jewish and Christian tradition point to the prophet Samuel. If it was Samuel, it would have been written before the year 1000 BC, which is about the latest date for Samuel’s death.

The main purpose of the Book of Ruth is to communicate the ancestry of King David, the greatest king of Israel, who would rule from 1010 to 970 BC. The events in Ruth likely take place around 1100 BC, or toward the end of the rule of the judges. The period of the judges would end when Saul was anointed as the first king of Israel in 1050 BC.

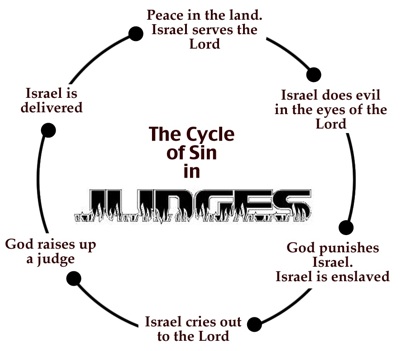

The story of Ruth is also a sharp contrast to the depressing history of the period of the judges. In contrast to the Canaanized judges (e.g., Gideon, Jephthah, and Samson), the characters in Ruth are, for the most part, faithful to God, kind in their dealings with each other, and otherwise exemplary individuals.

The story of Ruth is meant to tell the story of the bloodline of King David, the greatest king Israel would ever have. Ruth is David’s great-grandmother, but the writer of the Book of Ruth wants to chronicle how exactly it came to be that the great grandmother of David could be a foreign woman from Moab.

The story begins in chapter 1 with a husband, wife, and two sons leaving Bethlehem, a small town in the territory of Judah, to go to Moab, a neighboring nation that had been unfriendly to Israel in the past (recall that King Balak from the Book of Numbers was from Moab). The reason given is that there was a famine in Bethlehem.

Why was there a famine? Remember that the books of Leviticus (26:18-20) and Deuteronomy (28:23-24) both recorded God’s commitment to cursing Israel with famine if they chased after foreign gods, and we know from the Book of Judges that they certainly did.

The two sons married Moabite wives, but after 10 years, the father, Elimelech, and the two sons, Mahlon and Kilion, had died. Naomi, the widow of Elimelech, decided to travel back to Bethlehem because she heard that God had brought an end to the famine.

Naomi tells her two daughters-in-law that they should abandon her and go back to their Moabite families so that they could remarry. In the ancient world, an unmarried woman was in a very precarious position, as she had to rely on her relatives to support her. Naomi knew that the girls would be better off going back to their own families and finding new husbands than coming with her to Bethlehem in a foreign land where remarriage was unlikely.

One of the daughters-in-law, however, refuses to abandon Naomi, and pledges not only to accompany her, but to adopt Naomi’s people as her own, and Naomi’s God as her own. Her name is Ruth.

In chapter 2, after Naomi and Ruth have returned to Bethlehem, they are faced with the difficulty of getting food for themselves. Ruth volunteers to go to a local farmer’s field and gather the leftover grain from the harvesting that was going on at the time. Daniel Block, in Judges, Ruth: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture (The New American Commentary), explains:

The Mosaic law displayed particular compassion for the alien, the orphan, and the widow by prescribing that harvesters deliberately leave the grain in the corners of their fields for these economically vulnerable classes and not go back to gather (liqqēṭ) ears of grain they might have dropped (Lev 19:9, 10; 23:22; Deut 24:19). As a Moabite and a widow Ruth qualified to glean on two counts. But for these same two reasons she could not count on the goodwill of the locals, hence her concern to glean behind someone who would look upon her with favor.

Ruth happens to choose the fields of a man named Boaz, a relative of Naomi’s former husband Elimelech. Boaz arrives to find Ruth working hard in his fields to pick up the scraps of grain left over by his harvesters. After finding out that Ruth has forsaken her own people and country to help her poor widowed mother-in-law, he rewards Ruth’s efforts by 1) telling her to continue working in his fields, 2) promising her safety, 3) offering her water whenever she needs it, 4) feeding her a meal of bread, wine vinegar, and roasted grain, 5) and instructing his workers to leave behind extra grain for Ruth to gather.

Ruth returns home that evening with a large amount of grain and explains to Naomi Boaz’s generosity. Naomi thanks God for Boaz and tells Ruth to continue going to Boaz’s fields until the grain harvest is over. A young, widowed woman like Ruth would be in great danger from being raped, and so not only was Ruth able to gather plenty of food at Boaz’s fields, she would not have to worry about her safety.

In chapter 3, Naomi instructs Ruth to seek the hand of Boaz in marriage. Her reasoning is that Boaz is a close relative of her late husband, and that he is therefore obligated to buy the property that Elimelech and his sons left behind, but also obligated to marry the widow of Elimelech’s son, Mahlon, so that she can bear children which will grow up to claim that property.

Land was passed on from father to son, and since Naomi’s sons were dead, there was nobody to whom Elimelech’s land could pass. Naomi herself was too old to conceive any more children, but her daughter-in-law, Ruth, was young and able to conceive and bear children. If Ruth had children, those children would grow up and inherit the land owned by their grandfather. Otherwise, Elimelech’s descendants would lose the land forever.

Ruth was to go to a public threshing floor where Boaz would be working, and wait for him to go to sleep. The threshing floor was being used by Boaz to thresh and winnow the grain he had harvested. John Reed, in The Bible Knowledge Commentary, provides the setting:

The people of Bethlehem took turns using the threshing floor. The floor was a flat hard area on a slightly raised platform or hill. In threshing, the grain was beaten out from the stalks with flails (cf. 2:17) or was trodden over by oxen. Then in winnowing the grain was thrown in the air and the wind carried the chaff away. The grain was then removed from the threshing floor and placed in heaps to be sold or stored in granaries.

Threshing and winnowing were a time of great festivity and rejoicing. Naomi knew that Boaz was threshing his grain on the day that she had chosen for her plan. She also knew that Boaz would be sleeping near his grain that night, to protect it.

When Boaz went to sleep, Ruth was to lay down at his feet, uncover his feet, and wait. This was a customary way for a woman to signal that she was asking a man for marriage.

When Boaz awakes, he is stunned to find Ruth asking him for marriage. He is surprised because he is much older than her, and she chose him over other younger men. We can assume that Ruth was a very attractive young lady!

There is, however, a catch. Boaz tells Ruth that there is a closer relative than he who must be given the first chance to buy Elimelech’s land and marry Ruth. If this other man decides not to take the opportunity, Boaz will.

In chapter 4, Boaz gathers the elders of the town and offers the closer relative the land and Ruth in marriage. The man declines and lets Boaz buy the land and take Ruth as his wife instead. Why might the other man have declined? The text doesn’t tell us explicitly, but it seems that he is without sons and he is afraid that if he has children with Ruth, then his lands will pass to her sons in the names of Elimelech, Mahlon, and Kilion.

At the end of chapter 4, we learn that Ruth and Boaz do have a son named Obed. Obed becomes the father of Jesse, and Jesse becomes the father of David, the greatest king of Israel.

God’s hand can be seen throughout this narrative. First, God causes the famine which drove Elimelech and his family to Moab. Second, the clear implication is that God was at work when Ruth “happened” to end up in the fields of Boaz. Of all the fields she could have chosen, it was clearly providential that she chose Boaz’s fields.

Third, Block points out that Naomi’s plan for Ruth to petition Boaz for marriage was fraught with danger:

Ruth’s preparations and the choice of location for the encounter suggest the actions of a prostitute. Under normal circumstances, if a self-respecting and morally noble man like Boaz, sleeping at the threshing floor, should wake up in the middle of the night and discover a woman beside him, he would surely have shooed her off, protesting that he had nothing to do with women like her. But if Ruth’s actions are questionable ethically, her demand that Boaz marry her are highly irregular from the perspective of custom: a foreigner propositioning an Israelite; a woman propositioning a man; a young person propositioning an older person; a destitute field worker propositioning the landowner. But instead of taking offense at Ruth’s forwardness, Boaz blesses her, praises her for her ḥesed, calls her ‘my daughter,’ reassures her by telling her not to fear, promises to do whatever she asks, and pronounces her a noble woman (ʾēšet ḥayil). This extraordinary reaction is best attributed to the hand of God controlling his heart and his tongue when he awakes.

Fourth, God ensures that it is Boaz who marries Ruth, not the other relative. Fifth, and finally, God sees to it that Ruth bears a child, Obed, who will be the grandfather of King David. Why does David matter so much? Because God promised to bring the Messiah through David’s descendants. Reed writes,

“Jesus Christ’s lineage, through Mary, is traced to David (Matt. 1:1–16; cf. Rom. 1:3; 2 Tim. 2:8; Rev. 22:16). Christ is therefore called “the Son of David” (Matt. 15:22; 20:30–31; 21:9, 15; 22:42). Christ will someday return to earth and will sit on the throne of David as the millennial King (2 Sam. 7:12–16; Rev. 20:4–6).”

God fulfills his promises of a Messiah and a future redeemer of mankind, Jesus Christ, through the faithful actions of Ruth and Boaz, two godly people who lived 1000 years before He was born.

Toward the end of the period of the judges lived one of the most famous judges, Samson. He lived from approximately 1089 BC to 1049 BC. The story of Samson begins in chapter 13, which is where we pick up the narrative.

Toward the end of the period of the judges lived one of the most famous judges, Samson. He lived from approximately 1089 BC to 1049 BC. The story of Samson begins in chapter 13, which is where we pick up the narrative. Judges 1:8 says, “The men of Judah attacked Jerusalem also and took it. They put the city to the sword and set it on fire.” The surface implication is that the city of Jerusalem was completely destroyed and everyone inside of it killed.

Judges 1:8 says, “The men of Judah attacked Jerusalem also and took it. They put the city to the sword and set it on fire.” The surface implication is that the city of Jerusalem was completely destroyed and everyone inside of it killed. The Book of Judges continues the historical narrative where Joshua ended. The author of Judges is unknown, although Jewish tradition ascribes authorship to the prophet Samuel. Samuel may have written portions of the book, but there were likely later editors that compiled it into its final form. Scholars date the final composition of Judges from some time between 700 and 1000 BC.

The Book of Judges continues the historical narrative where Joshua ended. The author of Judges is unknown, although Jewish tradition ascribes authorship to the prophet Samuel. Samuel may have written portions of the book, but there were likely later editors that compiled it into its final form. Scholars date the final composition of Judges from some time between 700 and 1000 BC. While Jews and Christians have traditionally believed that Moses was the primary author of the Pentateuch, some biblical scholars today reject that belief. Instead, these scholars believe that the Pentateuch was written over several centuries by several different authors and not finally compiled into its final form until just a few hundred years before Jesus was born.

While Jews and Christians have traditionally believed that Moses was the primary author of the Pentateuch, some biblical scholars today reject that belief. Instead, these scholars believe that the Pentateuch was written over several centuries by several different authors and not finally compiled into its final form until just a few hundred years before Jesus was born.