In my last post, I conducted a poll as to whether or not the Nicene Creed is relevant and authoritative in Christianity today. Thus far, the results are as follows: 48% believe it to be both relevant and authoritative, 21% believe it to be relevant, but not authoritative, and a relatively small number (17%) believe it to be completely irrelevant. Given the tone of my post, you will find it no surprise that I fall in line with the majority opinion, holding the Nicene Creed to be both relevant and authoritative.

Those who oppose the idea of the creeds being relevant and authoritative often appeal to the doctrine of sola scriptura, i.e., the doctrine that scripture alone is authoritative. The general claim is that the Bible is the only authoritative source on Christian doctrine and life, and, as a result, the creeds can’t possibly carry any authority. This position grew out of the classic and radical reformers reaction to papal abuses, and quite honestly, I can understand the sentiment behind it.

However, those who hold this position often fail to realize that while our beliefs may be rooted in scripture, it is often not scripture itself that is believed. Instead, our beliefs are based upon our interpretation of scripture. For example, while the Bible says that God is one, it does not tell us exactly how God is one. Nevertheless, most conservative Christians assert that God is one in nature, essence, and being. These words and this belief are not explicitly taught in the Bible. Instead, they are inferred based upon what the Bible does say and are thus, an interpretation of the biblical teachings relative to the nature of God.

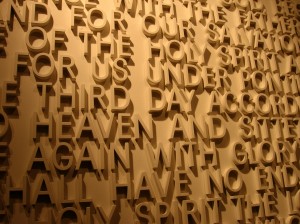

Personally, I believe this is exactly what the creeds are: correct interpretations of scripture contained in short statements of faith. However, I believe that their connection to Apostolic Tradition and the culmination of Church history have demonstrated them to be authoritative. Most of the creeds were hard won, coming at the expense of much blood, sweat, and tears. In large part, they have served as a source of unity for Christians, placing fences that help to delineate orthodoxy from heresy and heterodoxy. The Nicene Creed came out of a long, hard fought battle with the Arian Heresy (Mormonism’s ancient cousin) and answered the question of how God is one once and for all.

Admittedly, the belief that the creeds are authoritative is a position of faith. Epistemological certainty is impossible in an area such as this. However, it is a position of faith that is supported by good reason, logic, and evidence. In addition, those who believe they can’t be authoritative because “scripture alone is authoritative” hold their position to their own peril. For, if the creeds can’t be authoritatively correct because they aren’t scripture, how do you know your interpretation is correct and authoritative, and by what authority do you judge differing positions to be wrong? After all, your interpretation isn’t scripture.

Have a blessed day!

Darrell

The Book of Revelation, according to some Christians, teaches a literal thousand-year reign of Christ on earth after his second coming (see Rev. 20). This will then be followed by the creation of a new heaven and new earth. This view is known today as premillenialism.

The Book of Revelation, according to some Christians, teaches a literal thousand-year reign of Christ on earth after his second coming (see Rev. 20). This will then be followed by the creation of a new heaven and new earth. This view is known today as premillenialism.