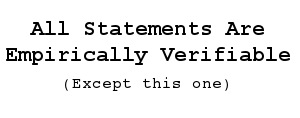

It’s been a while since we’ve beat up scientism on the blog, so I figured we were due again. It’s an “ism” that just keeps rearing its head over and over and thus needs to be slapped around over and over. Philosopher Edward Feser, in one of his blog posts, reviews yet another version of the argument for scientism that he then critiques. Here is the argument:

It’s been a while since we’ve beat up scientism on the blog, so I figured we were due again. It’s an “ism” that just keeps rearing its head over and over and thus needs to be slapped around over and over. Philosopher Edward Feser, in one of his blog posts, reviews yet another version of the argument for scientism that he then critiques. Here is the argument:

- The predictive power and technological applications of science are unparalleled by those of any other purported source of knowledge.

- So science is a reliable source of knowledge.

- Science has undermined beliefs derived from other purported sources of knowledge, such as common sense.

- So science has shown that these other purported sources of knowledge are unreliable.

- The range of subjects science investigates is vast.

- So the number of purported sources of knowledge that science has shown to be unreliable is vast.

- So what science reveals to us is probably all that is real.

Feser grants premise 1 and 2, but thinks that premise 3 is not sustainable (in the post he explains why). However, in order to move the critique along, he grants, for the sake of argument, premise 3, and then proceeds to look at premises 4-7.

[P]remise (3) simply doesn’t give us good reason to believe step (4). To see why not, suppose we replace “science” with “visual experience” in these two steps of the argument. Visual experience has of course very often undermined beliefs derived from other sources of knowledge. For example, it often tells us that the person we thought we heard come in the room was really someone else, or that when we thought we were feeling a pillow next to us it was really a cat.

Does that mean that visual experience has shown that auditory experience and tactile experience are unreliable sources of knowledge? Of course not. To do that, it would have to have shown that auditory experience and tactical experience are not just often wrong but wrong on a massive scale and with respect to a very wide variety of subjects. And it has done no such thing. But neither has science shown any such thing with respect to common sense. Hence (3) is not a good reason to conclude to (4).

But do premises 4 and 5 support premise 6? Not really.

(4) and (5) also don’t give us good reason to believe (6). Suppose we label the range of subjects science covers with letters, from A, B, C, D, and so on all the way to Z. Even if science really did show that other purported sources of knowledge were unreliable with respect to domains A and B (say), it obviously wouldn’t follow that there were no reliable sources of knowledge other than science with respect to domains C through Z.

Feser, referring to his book Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction (Editiones Scholasticae), summarizes the case against scientism:

In any event, a theme that is developed at length throughout my book is that there are absolute limits in principle to the range of beliefs that science could undermine, and these are precisely the sorts of beliefs with which metaphysics is concerned. The book aims in part to set out (some of) the notions that any possible empirical science must presuppose, and thus cannot coherently call into question.

Or put another way, science is built on a foundation of mathematics, logic, reliability of the senses, truth-telling, language, uniformity of nature, and so on. Without that foundation, science crumbles to the ground in a heap of debris.

Some naturalists are betting on it, because ultimately physical laws, in their worldview, have to explain everything. For the naturalist, there is nothing but physical reality which is governed by physical laws. That being the case, everything, including the human mind, must be reduced to the purely physical and mechanistic.

Some naturalists are betting on it, because ultimately physical laws, in their worldview, have to explain everything. For the naturalist, there is nothing but physical reality which is governed by physical laws. That being the case, everything, including the human mind, must be reduced to the purely physical and mechanistic. One of the most common charges that intelligent design (ID) opponents hurl at ID theorists is that ID is not real science. They will say that a real scientific theory must be testable against the empirical world, must make predictions, must be falsifiable, must be explanatory by reference to natural law, and so forth. They point to ID and say that it doesn’t meet all of these criteria, and therefore ID must not be science.

One of the most common charges that intelligent design (ID) opponents hurl at ID theorists is that ID is not real science. They will say that a real scientific theory must be testable against the empirical world, must make predictions, must be falsifiable, must be explanatory by reference to natural law, and so forth. They point to ID and say that it doesn’t meet all of these criteria, and therefore ID must not be science.