At the end of chapter 23, King Josiah is killed by the Egyptian Pharaoh Neco in 609 BC. Shortly thereafter Neco places one of Josiah’s sons, Jehoiakim, on the throne of Judah. Judah has now become a vassal of Egypt and the king heavily taxes his people in order to pay the tribute to Egypt.

At the end of chapter 23, King Josiah is killed by the Egyptian Pharaoh Neco in 609 BC. Shortly thereafter Neco places one of Josiah’s sons, Jehoiakim, on the throne of Judah. Judah has now become a vassal of Egypt and the king heavily taxes his people in order to pay the tribute to Egypt.

Chapters 24-25 of 2 Kings span the last 23 years of the nation of Judah. The account is rapid-fire and introduces numerous people to the reader. In order to help us see more clearly the order of events, I’ve placed a timeline below which is borrowed from Lawrence O. Richards’ The Teacher’s Commentary.

609 BC – Josiah slain in battle at Megiddo; Jehoiakim, son of Josiah, becomes king

605 BC – Babylon defeats Egypt at Carchemish; Nebuchadnezzar becomes king of Babylon; First deportation to Babylon includes Daniel

604 BC – Nebuchadnezzar receives tribute in Palestine

601 BC – Nebuchadnezzar defeated near Egypt

598 BC – Jehoiakim dies; Jehoiachin, son of Jehoiakim, rules from December 9, 598 to March 16, 597; is then deported April 22 to Babylon

597 BC – Nebuchadnezzar chooses Zedekiah, son of Josiah, to become king of Judah; Ezekiel taken to Babylon

588 BC – Babylon lays siege to Jerusalem on January 15

587 BC – Jeremiah imprisoned (Jer. 32:1–2)

586 BC – Zedekiah flees; He is captured and blinded by Nebuchadnezzar; A few months later, Nebuchadnezzar orders Jerusalem sacked and destroyed

In the final 23 years of Judah, there are actually three deportations. The first occurs in 605 BC when Nebuchadnezzar becomes the king of Babylon. He defeats Egypt and thus assumes control of all of Egypt’s vassal states, Judah being one of them. Nebuchadnezzar then marches into Judah and demands loyalty from Jehoiakim. Jehoiakim submits and allows Nebuchadnezzar to take some of the nobility and members of the royal family to Babylon. Daniel is among this first group of exiles.

The second deportation occurs in 597 BC when Nebuchadnezzar again marches on Jerusalem, this time because Jehoiakim is rebelling against Babylonian rule. By the time he arrives, Jehoiakim has already died and his son Jehoiachin is king. Jehoiachin surrenders to Nebuchadnezzar and is taken in captivity to Babylon.

This time around Nebuchadnezzar also takes many of the treasures of the temple and palace. He takes captive virtually all the military officers and 7,000 soldiers, as well as 1,000 craftsmen and artisans. Ten thousand people are taken captive, including Ezekiel.

The third and final deportation occurs in 586 BC after Nebuchadnezzar has again laid siege to Jerusalem. This time Nebuchadnezzar attacks because his puppet, King Zedekiah, has rebelled and joined forces with Egypt. Once Zedekiah is captured and hauled off to Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar sees to it that Judah will never again bother him.

Verses 8-17 in chapter 25 of 2 Kings recount the destruction. The Babylonians burn the temple, the palace, and all the major buildings in Jerusalem. The walls of the city are destroyed. Before burning the temple, the Babylonians carry off everything of value. Jerusalem, the city that David established as the capital of the united kingdom of Israel around 1000 BC, is now completely and utterly destroyed, with all but the poorest Israelites marched off to Babylon.

Paul R. House, in vol. 8, 1, 2 Kings, The New American Commentary, writes,

For covenant-minded readers the loss of the temple means much more than the destruction of a significant public building. To them the temple symbolizes God’s presence in the midst of the chosen people, ongoing worship of Yahweh, the possibility of receiving forgiveness by the offering of sacrifice, and the opportunity to gather as a unified nation at festival time. Of course, the temple was rarely used properly, yet as long as it stood, the hope for the ideal existed. Now what will happen to God’s people?

The unthinkable has finally occurred. After centuries of warnings, God has removed Israel from the Promised Land. Is the destruction of Jerusalem and the exile of the people a surprise? It shouldn’t be. The Mosaic covenant has been broken by king after king for centuries. The people of Israel and Judah have strayed further and further from loving Yahweh, instead choosing to worship false gods made of metal and wood. Paul House recounts the warnings given to the people of Israel ever since the days of Moses.

This event is the most devastating punishment Moses can use to threaten people who desperately seek a home of their own (Deut 27–28). It is what Israel barely avoids in Judges, what Samuel warns the people about in 1 Samuel 12, and what Solomon fears in 1 Kgs 8:22–61. Isaiah predicts the exile (Isa 39:1–8), as do Jeremiah (Jer 7:1–15), Ezekiel (Ezek 20:1–49), Amos (Amos 2:4–5; 6:1–7), Micah (Mic 3:12), Habakkuk (Hab 1:5–11), and Zephaniah (Zeph 1:4–13). Jeremiah and Ezekiel live during the exile, while Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi live in its aftermath. Clearly, it is one of the defining events in the Old Testament story.

Four biblical writers lived during the last days of Judah: Habakkuk, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel. Habakkuk and Jeremiah were both prophesying in and around Jerusalem, while Ezekiel and Daniel began their ministries after they had been exiled to Babylon during the first and second deportations (Daniel in 605 BC and Ezekiel in 597 BC).

Even though the people have been exiled and the land has been lost, God’s spokesmen continue to preach and write to the remnant of Israel. Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel all have important messages to give to the people of God (which we will study in the coming weeks). The destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BC is the end of an era, but it is not the end of God’s plan for Israel and the rest of the world.

King Ahab, the enemy of Elijah, has died and his son Ahaziah has taken his place as king of Israel (the year is 853 BC). Elijah is still the anointed prophet of God, but his time is coming to an end. Some years earlier Elijah had already selected his successor, a young man named Elisha (see 1 Kings 19), but Elijah had a few remaining things to take care of before he was taken to heaven by God Himself.

King Ahab, the enemy of Elijah, has died and his son Ahaziah has taken his place as king of Israel (the year is 853 BC). Elijah is still the anointed prophet of God, but his time is coming to an end. Some years earlier Elijah had already selected his successor, a young man named Elisha (see 1 Kings 19), but Elijah had a few remaining things to take care of before he was taken to heaven by God Himself. In the nation of Israel, since the division of the kingdom, there have been 7 kings and 4 different dynasties (successions of rulers who are of the same family). The year is 874 BC and the eighth king of Israel comes to the throne. His name is Ahab and his reign begins at about the time King Asa of Judah’s reign is ending.

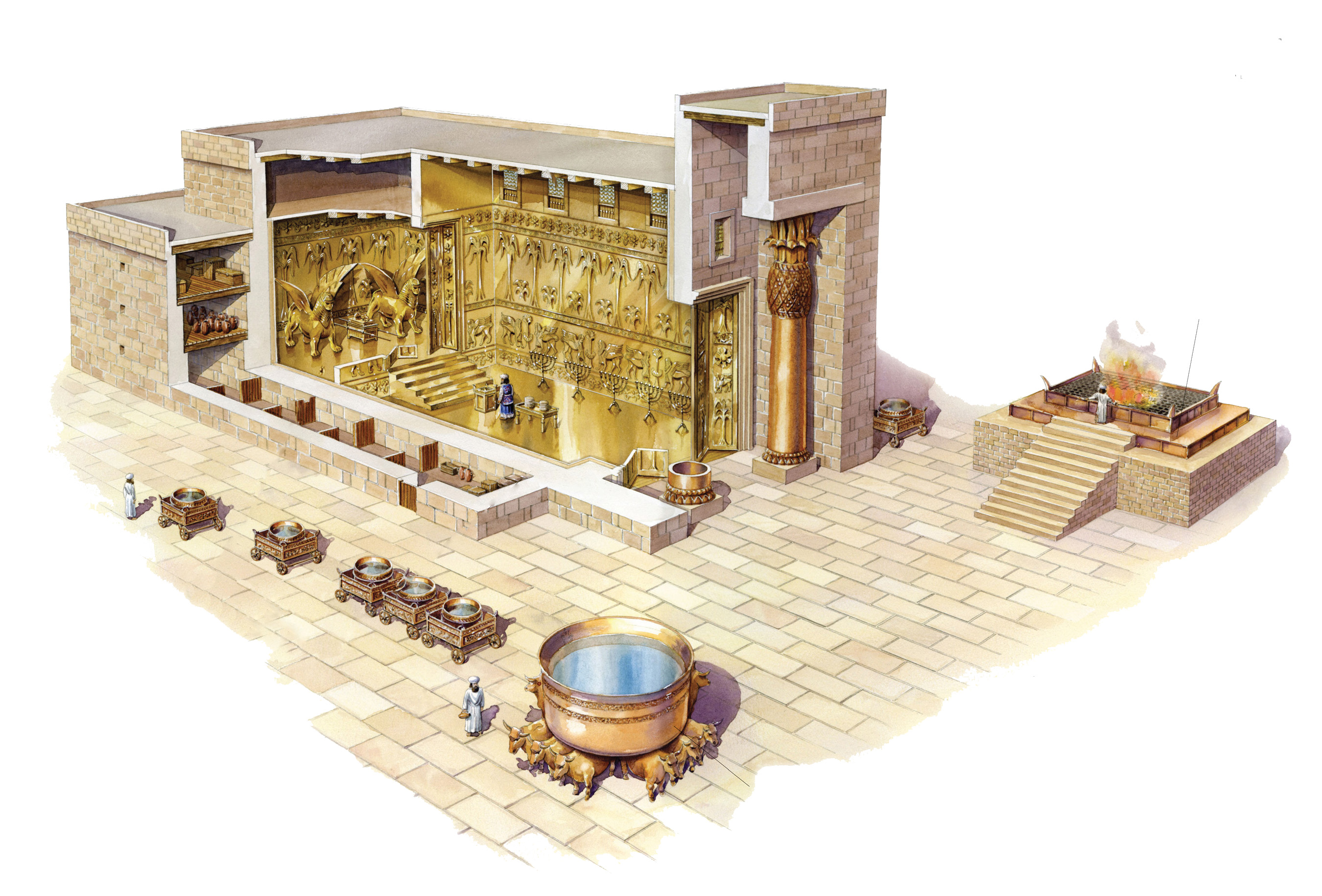

In the nation of Israel, since the division of the kingdom, there have been 7 kings and 4 different dynasties (successions of rulers who are of the same family). The year is 874 BC and the eighth king of Israel comes to the throne. His name is Ahab and his reign begins at about the time King Asa of Judah’s reign is ending. In chapters 6-8, the author reports the building of the temple that would become the permanent “home” of God among the Israelites. Verses 1-10, in chapter 6, tell us that temple construction began in 966 BC, Solomon’s fourth year as king. The project was completed and the temple dedicated 7 ½ years later. This structure would stand for almost four hundred years until it is destroyed by the Babylonians.

In chapters 6-8, the author reports the building of the temple that would become the permanent “home” of God among the Israelites. Verses 1-10, in chapter 6, tell us that temple construction began in 966 BC, Solomon’s fourth year as king. The project was completed and the temple dedicated 7 ½ years later. This structure would stand for almost four hundred years until it is destroyed by the Babylonians.