While there seems to be plenty of archaeological evidence of the existence of Israel’s and Judah’s kings after about 850 BC, there is little direct evidence of the existence of Saul, David, and Solomon’s kingdoms. Why is this?

While there seems to be plenty of archaeological evidence of the existence of Israel’s and Judah’s kings after about 850 BC, there is little direct evidence of the existence of Saul, David, and Solomon’s kingdoms. Why is this?

Kenneth A. Kitchen, in his On the Reliability of the Old Testament, dedicates an entire chapter to this topic. At the end of the chapter, he writes a summary which I quote at length below.

The information from external [nonbiblical] sources in terms of explicit mentions of biblical characters such as Saul, David, or Solomon is almost zero, until Shalmaneser III had hostile contact with Ahab of Israel in 853. The reasons for this are stunningly simple and conclusive. From Mesopotamia, no Assyrian rulers had had direct contact with Palestine before 853 — and so do not mention any local kings there. This is not the fault of the kings in Canaan, whether Israelite, Canaanite, or Philistine, and does not prove their nonexistence.

From Egypt we have virtually no historical inscriptions whatsoever mentioning Palestinian powers or entities between Ramesses III (ca. 1184-1153) and Shoshenq I (ca. 945-924). We have just two literary works, Wenamun, referring only to coastal ports (Dor to Byblos), and the Moscow Literary Letter that knows of Seir. Plus the fragmentary triumphal scene of Siamun (ca. 979/978-960/959), overlapping with the early years of Solomon (970-960), when a pharaoh smote Gezer and ceded it to him (1 Kings 9:16). The vast mass of Egyptian records in the Delta and Memphis is long since lost for nearly all periods, including the tenth century. At Thebes, almost all records are local, private, and on funerary religion, not foreign wars.

From the Levant, original texts are so far lost/undiscovered before the ninth century, except at Byblos, whose kings celebrate only themselves. We have nothing from Tyre, Sidon, Damascus, etc., until much later. So, again, there is no mention of the Hebrew tenth-century monarchs — and, again, it is not their fault, and certainly not proof of nonexistence.

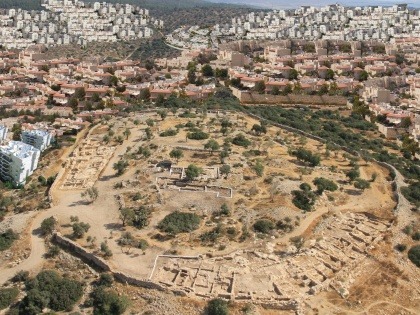

In Israel itself, the deplorable state of pre-Herodian remains in oldest Jerusalem (Ophel and the eastern ridge), inaccessibility of much of its terrain, and the fact that it is 95 percent undug/undiggable (100 percent on the Temple Mount, where royal stelae might have been erected) — all these factors almost entirely exclude any hope of retrieving significant inscriptions from Jerusalem at any period before Herodian times. (The Siloam tunnel text [ca. 700] survived precisely because it was in a safely buried location.) So, again, we cannot blame a David or a Solomon for all that happened to Jerusalem after their time. (emphasis in original)

In a nutshell, most of the archaeological records we have from the early first millennium BC originate from the two superpowers of the region, Assyria and Egypt. The Assyrians did not have contact with Israel until 850 BC and there is a 200-year gap in the Egyptian records which overlaps the reigns of Saul, David, and Solomon. Excavation in Jerusalem is difficult because of the location of the Temple Mount.

As an aside, archaeologist Eilat Mazar has more recently claimed to have found walls built by Solomon and sections of David’s palace in Jerusalem, but those findings are hotly contested, so we can’t draw any conclusions yet.

More from Kitchen in part 2 . . .

We have featured the findings of archaeologist Eilat Mazar in previous blog posts (

We have featured the findings of archaeologist Eilat Mazar in previous blog posts (