The traditional view of the Gospel of Luke is that it was written by Luke, a physician, friend, and missionary companion of the apostle Paul between AD 50-60. The Gospel of Luke is part one of a two-part work, with the second part being the book of Acts. Luke-Acts appear to be the only works in the New Testament written by a Gentile.

Michael J. Wilkins, in Matthew, Mark, Luke: Volume One (Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary), explains that

Luke writes as a second-generation Christian, claiming not to have been an eyewitness of the events of Jesus’ ministry, but to have thoroughly investigated the events before composing his Gospel (Luke 1:1–4). He writes as both historian and theologian, seeking to provide an accurate and trustworthy account of the events, while confirming the profound spiritual significance of these events.

Wilkins highlights the following purposes for Luke’s Gospel:

Luke’s prologue identifies his general purpose as the confirmation of the gospel, seeking to confirm for Theophilus ‘the certainty of the things you have been taught’ (1:1–4). More specifically, Luke appears to be writing for a Christian community—probably predominantly Gentile, but with Jewish representation—struggling to legitimize its claim as the authentic people of God, the heirs of the promises made to Israel. In defending the identity of Christ, Luke seeks to show that Jesus is the Messiah promised in the Old Testament and that his death and resurrection were part of God’s purpose and plan. In defense of the increasingly Gentile church, he confirms that all along it was God’s plan to bring salvation to the Gentiles, and that Israel’s rejection of the gospel was predicted in Scripture and was part of her history as a stubborn and resistant people. The theme that holds these threads together is promise and fulfillment. The church made up of Jews and Gentiles is the true people of God because it is for her and through her God’s promises are being fulfilled.

The first twenty-five verses of chapter one of the Gospel of Luke describe an angelic visit to a priest named Zechariah. The angel Gabriel tells Zechariah that he and his barren, elderly wife, Elizabeth, will conceive a child. The child will be a great prophet of God who will prepare Israel for the coming of the Lord. They are to name the child John.

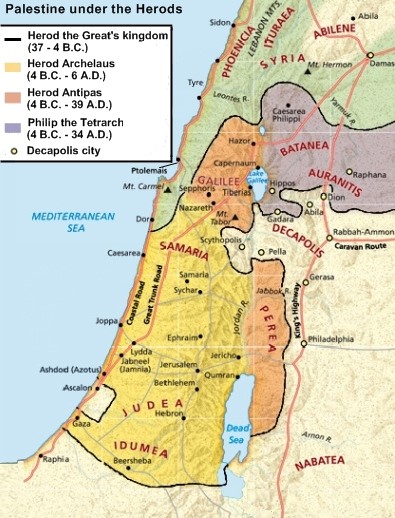

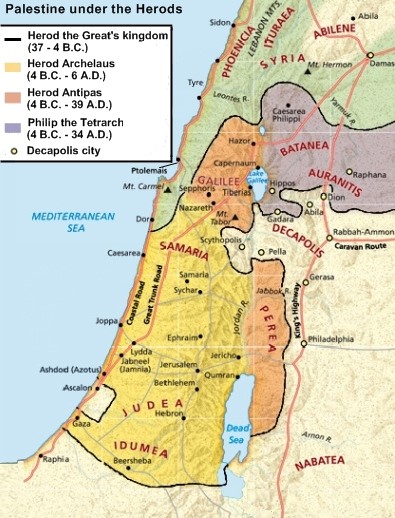

Starting in verse 26, the narrative describes another visit by Gabriel, but this time to a young virgin named Mary. Mary is a relative of Elizabeth, although we are unsure how they are related. Mary is engaged to be married to Joseph, who is a descendant of King David. They both live in a small town of less than two thousand people named Nazareth. Nazareth is located in the region of Galilee, which is part of the kingdom of Herod the Great (see map below). Herod is ruling greater Palestine under the authority of the Roman emperor Augustus.

Jewish tradition prescribes two stages of marriage: engagement followed by the marriage itself. Robert H. Stein explains in vol. 24, Luke, The New American Commentary:

Engagement involved a formal agreement initiated by a father seeking a wife for his son. The next most important person involved was the father of the bride. A son’s opinion would be sought more often in the process than a daughter’s. Upon payment of a purchase price to the bride’s father (for he lost a daughter and helper whereas the son’s family gained one) and a written agreement and/or oath by the son, the couple was engaged. Although during this stage the couple in some instances cohabited, this was the exception. An engagement was legally binding, and any sexual contact by the daughter with another person was considered adultery. The engagement could not be broken save through divorce (Matt 1:19), and the parties during this period were considered husband and wife (Matt 1:19–20, 24). At this time Mary likely was no more than fifteen years old, probably closer to thirteen, which was the normal age for betrothal.

Gabriel visits Mary and tells her that God has chosen her for a very special role. She will conceive a son and she will call him Jesus. This son will be like no other child that was ever or will ever be born. Gabriel explains to Mary that Jesus “will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. And the Lord God will give to him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end.”

Jesus will be the Son of God Himself, the promised Messiah, the promised descendant of David who will reign forever. Jesus will fulfill the prophecies found in 2 Sam 7:12–13, 16; Pss 89:4, 29; 132:12; Isa 9:7; and Dan 7:13–14.

Notice the contrasts between the birth announcement of John the Baptist and of Jesus. Stein writes:

John was ‘great in the sight of the Lord’ (1:15), but Jesus is ‘great’ (1:32), and his greatness is unqualified. Whereas John is later described as ‘a prophet of the Most High’ (1:76), Jesus is the ‘Son of the Most High’ (1:32). Whereas John’s birth was miraculous and had OT parallels, Jesus’ birth was even more miraculous. John’s conception, like that of Isaac, Samson, and Samuel, was miraculous; but Jesus’ conception was absolutely unique. It was not just quantitatively greater; it was qualitatively different. Whereas John’s task was to prepare for the Coming One (1:17, 76–79), Jesus is the Coming One who will reign forever (1:33); and whereas John was filled with the Spirit while still in the womb (1:15), Jesus’ very conception would be due to the Spirit’s miraculous activity in a virgin (1:35–37).

Mary asks Gabriel how she can become pregnant if she is still a virgin. Gabriel answers that the Holy Spirit will “overshadow” her and cause her to conceive. Gabriel does not explain how the Holy Spirit will cause her to conceive a child, but the clear implication is that the child will not have a human biological father. Jesus would be set apart for the service of God, thus he would be the “holy Son of God.”

Gabriel then tells Mary that her elderly relative Elizabeth is already miraculously six months pregnant. For God, nothing is impossible! Recall that this language is similar to what God told Abraham when Sarah laughed about conceiving a child in her old age (Gen 18:14). Mary, unlike Sarah, simply accepted the message from God and said “let it be to me according to your word.”

The remainder of chapter one records the birth of John the Baptist, the great prophet who would one day prepare the way for Jesus.

Chapter two, verses 1-21, present the famous Lukan birth narrative with which every Christian is familiar.

The Roman emperor Augustus Caesar frequently commissioned tax censuses to be taken in the various provinces of the Roman Empire. Evidently there is a census taking place around 4-6 BC. Joseph and Mary travel from their home in Nazareth to the town of Bethlehem, a distance of about ninety miles. Bethlehem is the birthplace of King David and we have already learned that Joseph is a descendant of David. It seems quite plausible that the reason Joseph travels to Bethlehem for the tax census is because he owns property there. Mary and Joseph may have been born in Bethlehem and moved to Nazareth later in life. With a tax census underway, they would need to return to their property so that it could be counted in the census.

After they had arrived in Bethlehem, Mary gives birth to Jesus. She wraps him in swaddling clothes and lays him in an animal feeding trough (manger) because there is no room in the inn. The circumstances of Jesus’ birth have been distorted over the millennia, so let’s take a closer look at what happened.

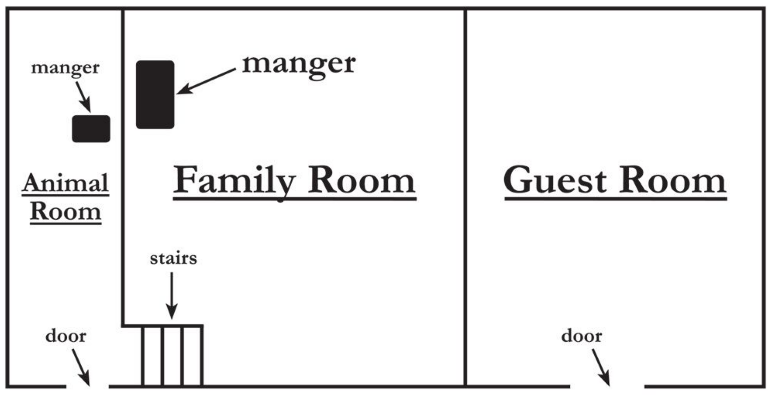

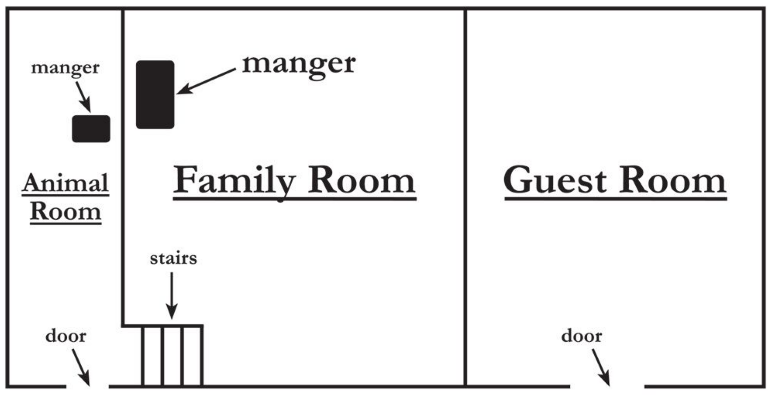

It is highly unlikely, given the importance of hospitality in first century Jewish culture, that Mary and Joseph would be unable to find a place to stay while they were in Bethlehem. It is much more probable that they were staying with family or friends. A typical house at this time consisted of a single story with two rooms, one being a guest room. Take a look at the floorplan below, taken from David A. Croteau’s Urban Legends of the New Testament.

According to Croteau, the Greek word translated as “inn” in verse 7 is better translated as “guest room.” So verse 7 should read “She wrapped him in cloths and placed him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the guest room.”

The guest room in the house they were staying must have been occupied by other guests. Therefore Mary and Joseph were sleeping in the family room along with the household owners. Now why in the world are there animal troughs in the house?

It was very common at this time for domesticated animals to be kept in the house with the owners. Croteau explains the typical arrangement:

A first-century house in Israel would have a large family room where the family would eat, cook, sleep, and do general living. At the end of the room there would be some steps down to a lower level, going down only a couple of feet. That lower level would be the ‘animal room’ of the house. There was no wall separating the rooms, just one room with two parts: the family room and the animal room. They would construct it so it slanted slightly toward the animal area for easy cleaning because the exterior door would be in the animal area. On the raised surface in the family room would be a feeding trough for the larger animals carved out of the floor. The larger animals in the animal area, like a cow or a donkey, could walk over and eat out of this trough. The smaller animals, like sheep, would have a smaller manger that would be carved out of the floor in the animal room, or the family might have a wooden trough that could be brought inside.

Given these conditions, Croteau argues that the manger Jesus was laid in was most likely the large feeding trough in the family room.

Verses 8-20 record the famous story of the angelic visitation to the shepherds. The shepherds are tending sheep at night, in an area not too far from Bethlehem. Some scholars speculate that these shepherds are caring for the lambs that will be sacrificed at the temple in Jerusalem, but we can’t be sure. Since shepherds only tended sheep at night during warmer months, it is likely that this took place between the months of March and November.

The angel announces that he has good news for the nation of Israel (that is what Luke means when he says “all the people” in verse 10). The good news is that the promised Messiah is born in Bethlehem (city of David), just as the prophecies predicted. Recall that the events of the book of Ruth (she is an ancestor of David) took place in Bethlehem, and that David grew up in Bethlehem. Michael J. Wilkins writes,

The announcement of good news (euangelizomai) is a common verb for Luke and has its roots in Isaiah’s announcement of end-time salvation (Isa. 52:7; 61:1). There is also an interesting parallel in an inscription found at Priene celebrating the birth of Augustus. The inscription calls him a ‘savior’ and says that ‘the birth date of our God has signaled the beginning of good news for the world.’ Both of these backgrounds could have had significance for Luke, who has just referred to Caesar Augustus (2:1) and for whom Isaiah’s portrait of salvation plays a leading role (2:32; 3:4–6; 4:18–19). Though Augustus is acclaimed by many as the world’s god and savior, Jesus is the true deliverer.

The shepherds are to go to nearby Bethlehem and search the houses until they find a newborn baby laying in a feeding trough. Given that Bethlehem is relatively small, the shepherds wouldn’t need long to find the baby. When they find this baby, they will know that the angelic visitor has spoken the truth.

The angel is then joined by a multitude of other angels who praise God for the birth of the child. Once the angelic chorus ends, the shepherds immediately hurry to Bethlehem to find the baby. They do indeed find Joseph, Mary, and the baby Jesus, and they proceed to spread the word about this miraculous child, the promised Messiah.

Why did God choose shepherds to be the first to hear the good news of Jesus’ birth? Many important biblical characters were shepherds, including Abraham, Moses, and David. In addition, God is often compared to a shepherd (e.g., Ps 23:1, Gen 49:24, Ps 80:1). It seems only fitting that shepherds would be the first witnesses to the birth of Jesus. Shepherds were also in a lower economic class, so God was demonstrating that the good news was for the poor and humble, not only for the rich.