The traditional view of the book of Revelation is that it was written by John, the beloved disciple of Jesus, the son of Zebedee, brother of James, and writer of the fourth Gospel and three letters in the New Testament. The book is most commonly dated around AD 95, although a significant minority of scholars date the book to AD 69.

The immediate context for the author and initial hearers of the book, according to A. Boyd Luter Jr. in [amazon_textlink asin=’1433613549′ text=’The Apologetics Study Bible‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’7e603b5a-9264-11e7-9c12-134df923f5b5′], was “a group of churches (1: 11; chaps. 2– 3) experiencing selective persecution (2: 9-10,13) in the midst of doctrinal and practical problems (2: 6,13-15,20-23), set against the backdrop of unseen but powerful spiritual warfare (2: 10; 9: 1,11; 12: 3-4,9-10; 20: 2).”

Regarding literary genre, Craig Keener, in [amazon_textlink asin=’0830824782′ text=’The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’9e43608e-9264-11e7-9688-93c20e591652′], writes:

Revelation mixes elements of Old Testament prophecy with a heavy dose of the apocalyptic genre, a style of writing that grew out of elements of Old Testament prophecy. Although nearly all its images have parallels in the biblical prophets, the images most relevant to late-first-century readers, which were prominent in popular Jewish revelations about the end time, are stressed most heavily. Chapters 2–3 are ‘oracular letters,’ a kind of letter occurring especially in the Old Testament (e.g., Jer 29:1–23, 29–32) but also attested on some Greek pottery fragments.

Steve Gregg, in [amazon_textlink asin=’1401676219′ text=’Revelation: Four Views‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’3634c73f-9265-11e7-8633-7308a2436992′], adds:

Unlike most other books of the New Testament, Revelation does not contain even one direct quotation from the Old Testament. However, there are hundreds of allusions to familiar images and phrases from the Old Testament, and from the New Testament as well (especially the other writings of John). It has been calculated that concepts and imagery are drawn from Isaiah (79 times), Daniel (53 times), Ezekiel (48 times), Psalms (43 times), Exodus (27 times), Jeremiah (22 times), Zechariah (15 times), Amos (9 times), and Joel (8 times). The principal historical matrices from which the images frequently are taken are: a) the Exodus, b) the Babylonian exile, and c) the life of Jesus.

The last few chapters of Revelation describe the end of the world and the return of Jesus Christ to reign over a new heaven and new earth. Thus, John starts with the hardships and sins predominating the first-century churches and extends these topics all the way out to the ultimate end of the age alluded to so often in the rest of the Bible. Keener writes:

Revelation provides an eternal perspective, by emphasizing such themes as the antagonism of the world in rebellion against God toward a church obedient to God’s will; the unity of the church’s worship with heaven’s worship; that victory depends on Christ’s finished work, not on human circumstances; that Christians must be ready to face death for Christ’s honor; that representatives of every people will ultimately stand before his throne; that the imminent hope of his return is worth more than all this world’s goods; and so forth. From the beginning, the Old Testament covenant and promise had implied a hope for the future of God’s people. When Israel was confronted with the question of individuals’ future, the Old Testament doctrines of justice and hope led them to views like the resurrection (Is 26:19; Dan 12:2). The future hope is further developed and embroidered with the imagery of Revelation.

The first three verses in Revelation form a prologue which some scholars believe was written by John’s followers after he died since it is in the third person. However, it also possible John wrote the prologue himself.

In verses 1-2, the author tells us that the words captured in the book were given by God the Father to Jesus, who gave the words to an angel, who gave the words to John, who finally gave the words to the people of God. The words of this book come in an unbroken chain from the sovereign Creator of the universe.

Also, the things recorded herein “must soon take place” (verse 1) and the “time is near” (verse 3). Those who argue that Revelation should be dated in AD 69 claim that many, if not all, of the prophecies in the book were fulfilled when Jerusalem and the temple were destroyed by Titus in AD 70. Thus, the events predicted in Revelation did indeed happen very soon after the book was written and delivered to the churches.

Those who date the book around AD 95 interpret “must soon take place” and the “time is near” differently. George Eldon Ladd, in [amazon_textlink asin=’0802816843′ text=’A Commentary on the Revelation of John‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’65d3c985-9265-11e7-a51e-b98a53188489′], is representative of this view:

We pointed out in the introduction that the Old Testament prophets blended the near and the distant perspectives so as to form a single canvas. Biblical prophecy is not primarily three-dimensional but two; it has height and breadth but is little concerned about depth, i.e., the chronology of future events. There is in biblical prophecy a tension between the immediate and the distant future; the distant is viewed through the transparency of the immediate. It is true that the early church lived in expectancy of the return of the Lord, and it is the nature of biblical prophecy to make it possible for every generation to live in expectancy of the end. To relax and say ‘where is the promise of his coming?’ is to become a scoffer of divine truth. The ‘biblical’ attitude is ‘take heed, watch, for you do not know when the time will come’ (Mark 13:33).

Finally, in verse 3 the author blesses the person who will stand in front of the seven churches and read aloud the book. Less than 50% of people could read in the first century, so it was customary practice to read aloud to a congregation the entire contents of a letter or book. The author also blesses the person who listens to the words in Revelation and obeys them.

In verses 4-8 we have the greeting from John. He is addressing seven specific churches in Asia (although the contents were meant to be shared by all churches) and he extends grace and peace from the Father, Holy Spirit, and Son. The Father is “him who is and who was and who is to come,” the Holy Spirit is referenced as “the seven spirits who are before his throne,” and the Son is “Jesus Christ the faithful witness, the firstborn of the dead, and the ruler of kings on earth.”

Ladd expands on the reference to the Holy Spirit:

From the seven spirits means from the Holy Spirit in his sevenfold fullness (cf. 3:1; 4:5; 5:6). Some have seen here a reference to angelic beings; but since the preceding phrase refers to God the Father and the following phrase to God the Son, it is certain that John included a reference to God the Holy Spirit, thus including all persons of the Godhead. In other places the New Testament speaks of the Holy Spirit in his plurality of functions (cf. Heb. 2:4; 1 Cor. 12:11; 14:32; Rev. 22:6). The source of the idea appears to be Zech. 4, where the prophet described a candlestick with seven lamps which are the eyes of the Lord ranging over the whole earth. The meaning of the vision was, ‘Not by might, not by power, but by my Spirit, says the Lord of hosts’ (Zech. 4:8).

Verses 5-7 then give a prolonged word of praise and worship to Jesus Christ specifically. John lists the following attributes of Jesus: 1) He loves us, 2) He freed us from sin by dying on the cross, 3) He is one day coming in judgment over the entire world.

Verse 8 reiterates the divine source and authority of John’s words. Ladd explains:

Alpha and Omega are the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet and therefore include all that is contained between them. God is the absolute beginning and the end, and therefore Lord of all that happens in human history. He is at the same time the eternal one, the transcendent one, who is unaffected by the conflicts of history, the one who is and who was and who is to come. As the one who is to come, he will yet visit men to bring history to its divinely decreed consummation. The Almighty can be better translated ‘the All-Ruler.’

Verses 9-20 contain the first vision John receives. John tells his readers that he was on the island of Patmos because of his teaching about Jesus. John was most likely banished to Patmos for about a year. Grant Osborne, in [amazon_textlink asin=’0801022991′ text=’Revelation, Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament’ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’8cea0b58-9265-11e7-9cca-2da6fa4ef666′], provides background:

Most likely John was temporarily banished there for proclaiming the gospel (see below). Ancient writers (e.g., Tacitus, Pliny) tell us that Patmos, a volcanic and rocky island, was one of three among the Sporades chain in the Aegean Sea. It was about ten miles long and six wide and was located thirty-seven miles southwest of Miletus, a harbor city near Ephesus. Therefore it is likely that Eusebius (Eccl. Hist. 3.18–20) was correct when he said John was banished there (according to him, in the fourteenth year [a.d. 95] of Domitian’s reign). Life there was not too harsh, as indicated by its decent-size population and two gymnasia as well as a temple of Artemis. Thus John would have lived a fairly normal life as an exile on that island. He was likely there only a short time and was allowed to go to Ephesus in a general amnesty for exiles by the emperor Nerva in a.d. 96 after Domitian died (see Aune 1997: 77; Carroll, ABD 5:178–79).

One Sunday, as John is worshiping, he hears a loud voice behind him: “Write what you see in a book and send it to the seven churches, to Ephesus and to Smyrna and to Pergamum and to Thyatira and to Sardis and to Philadelphia and to Laodicea.”

There were more than seven churches in Asia, so why these seven? Osborne explains:

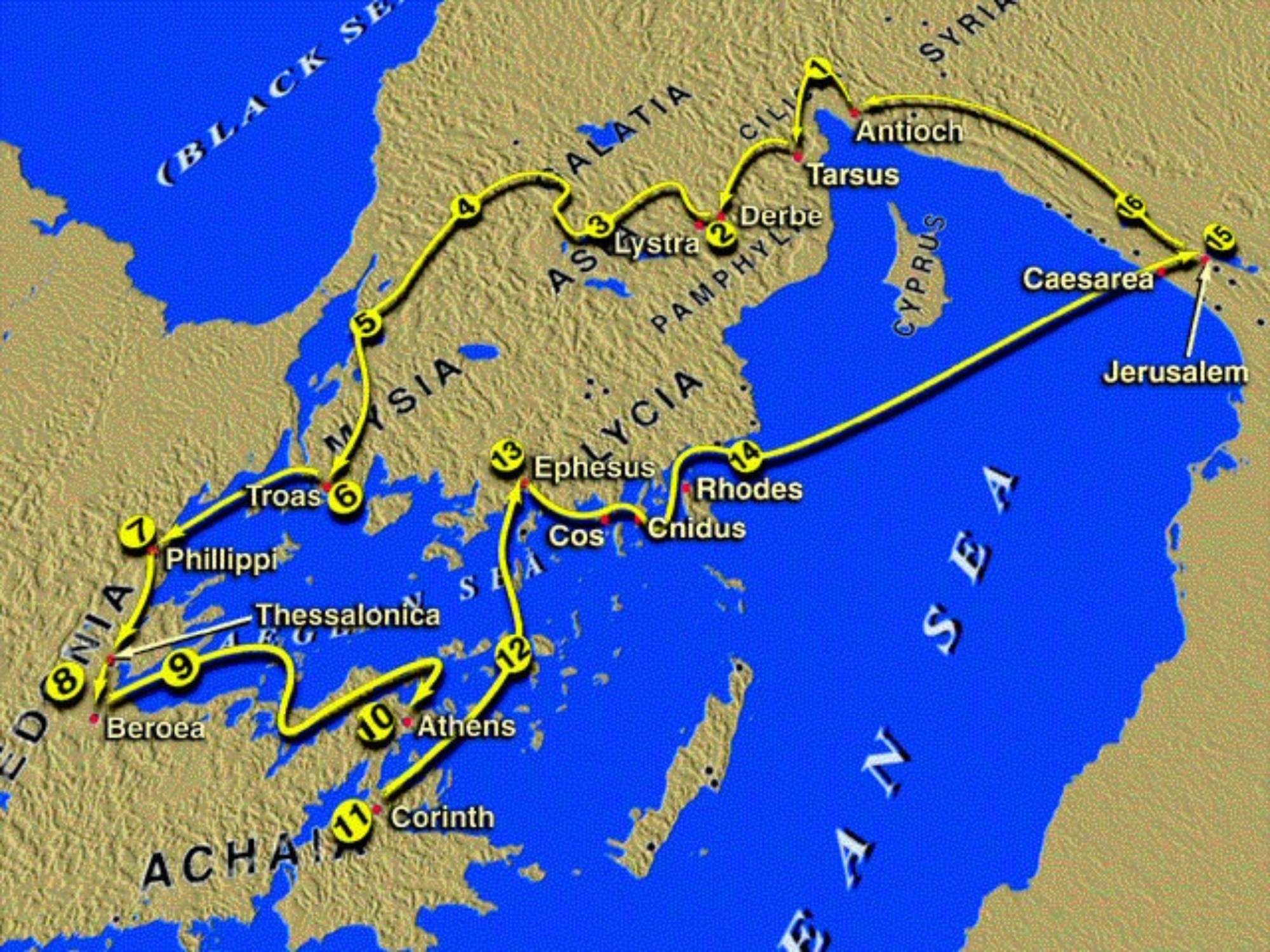

The order of the cities is significant, for they form the circular route of a letter carrier beginning at Ephesus and moving first north to Smyrna and to Pergamum, then turning southeast to Thyatira, south to Sardis, east to Philadelphia, and finally southeast to Laodicea. Also, we must ask why these particular cities are chosen. Troas and Colosse were critical NT centers, and Magnesia and Tralles were more important cities than Philadelphia or Thyatira. The best solution is still probably that of William Ramsay, as argued further by Hemer (1986: 14–15). These seven cities formed a natural center of communication for the rest of the province, since they were in order of sequence on an inner circular route through the territory. There is good reason to suppose that since Pauline times they had become ‘organizational and distributive centers’ from which messages would disseminate to the other churches of the province. DeSilva (1990: 193) also points out that these particular cities were chosen partly for their relationship to the imperial cult. All but Thyatira had temples dedicated to the emperors, and all but Philadelphia and Laodicea had imperial priests and altars. I would add one other point. They also represented the problems of the other churches in the area (note how each letter includes ‘Hear what the Spirit says to the churches’). As we will see, each town had its own particular set of problems but also served as examples for the other churches.

John turns around to see who is speaking and he sees seven lampstands which he later learns represent the seven churches. Note the connection between the seven lampstands and the seven candles of the lampstand (the menorah) in the tabernacle constructed in Exodus 25. These seven lampstands depict the churches as shining lights for God in the midst of the world.

Verses 13-16 then describe a “son of man” who is standing amid the lampstands (churches). This son of man, of course, refers to Jesus. John now uses several images to communicate important characteristics of Jesus, as he sees him in the vision. These images closely resemble the divine messenger sent to Daniel in Daniel 10:5-6, but they also reflect other biblical passage (noted below):

- The long robe and golden sash around his chest likely point to his high rank (only nobility would wear a sash around their chests instead of waist) and possibly priesthood. (Ex 28:4; Dan 10:5)

- His white hair is emblematic of age, honor, and wisdom. (Dan 7:9; Mark 9:3)

- His eyes of fire convey his piercing and all-knowing vision. (Dan 10:6)

- His burnished bronze feet emphasize his glory and strength, and his ability to render divine judgment. (Ezek 1:7; Dan 10:6)

- His voice of roaring waters signifies power and strength. (Ezek 1:24)

- The seven stars in his right hand indicate his complete control over the seven angels of the seven churches. (Ps 110:1; Matt 26:64)

- The sword coming out of his mouth symbolizes his words and then acts of judgment. (Is 11:4; Luke 2:35)

- His radiant face sums up the other images and reminds us of Jesus’ divine glory. (Matt 17:2; Ps 84:11; Is 60:19)

John’s reaction to seeing the glorified Jesus is natural: He falls at “his feet as though dead.” In verses 17-18, Jesus lays his hand on John and tells him not to fear. Jesus is the “first and the last,” just as the Father is the “Alpha and Omega.” Jesus reminds John that he died, but was resurrected, and will continue living forever. Jesus now holds the keys to the land of the dead. He can open the gate and allow the dead to return to life, and this is exactly what he will one day do.

Jesus then instructs John to write down everything he has seen and will see in the visions he is receiving. Everything must be recorded. Finally, in verse 20 Jesus explains that the seven lampstands are the seven churches and the seven stars are the seven angels of the seven churches.

There is much disagreement over what the seven angels represent. George Ladd weighs the different views:

The expression, the angels of the seven churches, represented by the seven stars in the hand of Christ, is difficult, especially since each of the seven letters was addressed to the angel of each respective church. This fact has led many commentators to conclude that the angel stood for the bishop of the church. This would be a good solution for the problem except for the fact that it violates the New Testament usage. Aggelos was not used of Christian leaders, and in the seven letters, neither angels nor bishops were rebuked. Another meaning of aggelos is ‘messenger,’ and the ‘angels’ are taken to be the seven messengers who carried the letters to the seven churches of Asia. If this is so, it is difficult to see why the letters were addressed to the messengers rather than to the churches themselves. The proper meaning of the word is angel, and the natural idea is that churches on earth have angels in heaven who represent them. However, the feature of angels symbolizing or representing men is lacking in all apocalyptic literature. Some have felt that the angels are guardian angels of the churches. It is best to understand this as a rather unusual symbol to represent the heavenly or supernatural character of the church.