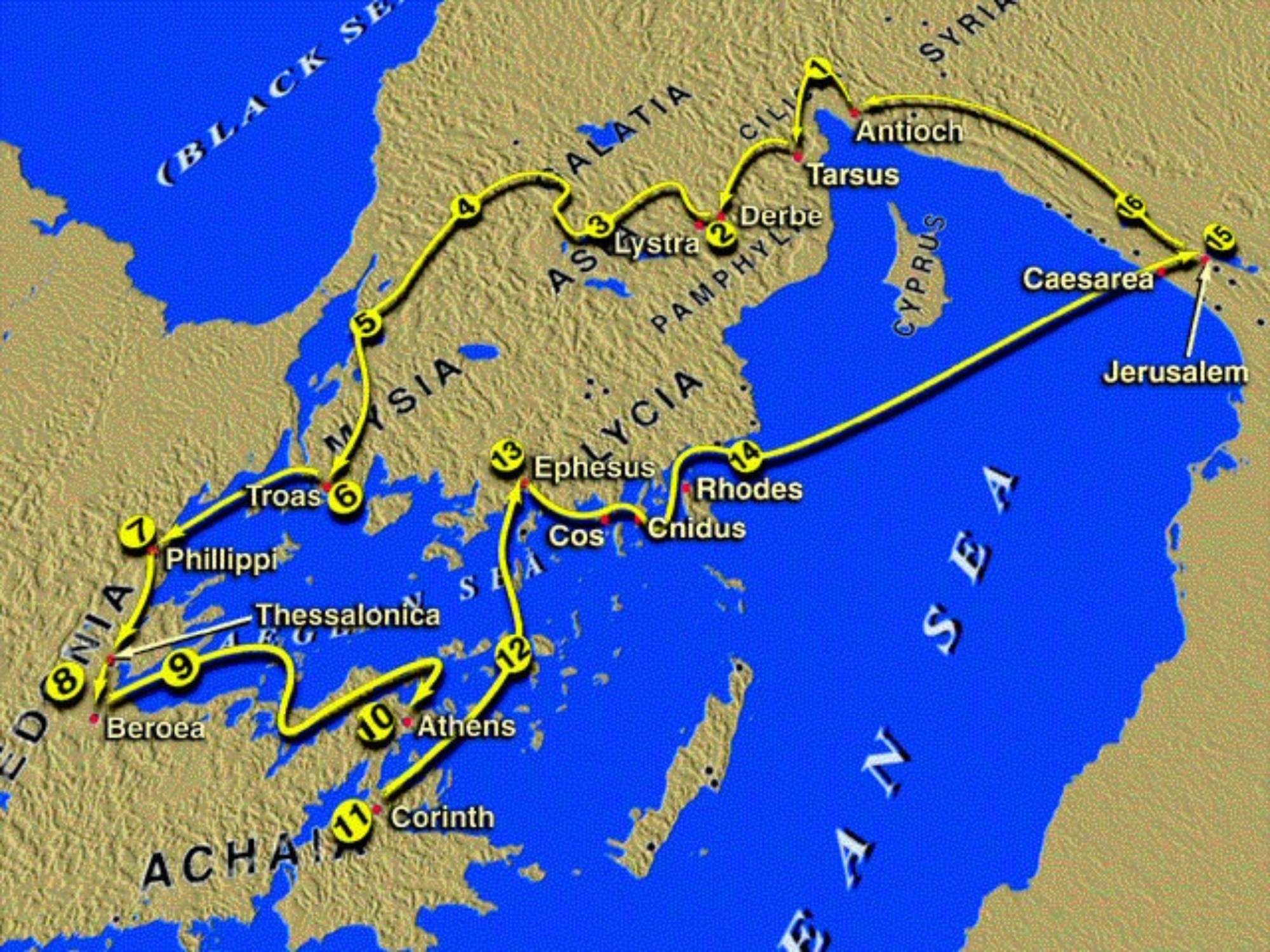

After the Jerusalem Council in AD 49 (Acts 15), Paul sets off on his second major missionary journey. The map below plots his course. In this lesson, we are picking up the story at location 10 on the map. Location 10 is the famous city of Athens, and Paul’s time there is described in Acts 17:16-34.

Craig Keener, in [amazon_textlink asin=’0830824782′ text=’The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’4f3eec98-86ac-11e7-ae8a-8b1da8f764fd’], writes,

Athens’ fame rested mainly on the glories of its past; even as a philosophical center, its primacy was challenged by other centers in the East like Alexandria and Tarsus. But Athens remained the symbol of the great philosophers in popular opinion, so much so that later rabbis liked to tell stories of earlier rabbis besting Athenian philosophers in debate.

When Paul arrives in Athens, he becomes greatly distressed at the incredible number of statues, idols, and altars dedicated to Greek gods. Clinton Arnold, in [amazon_textlink asin=’B004MPROQC’ text=’John, Acts: Volume Two (Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary)‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’75244f08-86ac-11e7-8f49-b549873f333f’] describes a subset of the gods worshiped in Athens:

Athena, the patron goddess of Athens, was probably the most popular with temples and edifices dedicated to her. Certainly every deity of the Greek pantheon was worshiped here. These included Zeus, Hera, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Aphrodite, Asclepius, Athena Nike, Athena Polias, Castor and Pollux, Demeter, Dionysus, the Erinyes, Eros, Ge, the Graces, Hades (Pluto), Hephaestus (Vulcan), Hekate, Heracles, Hermes, Hestia, Pan, Persephone, and Poseidon. A vast number of images of Hermes could be found all over the city and particularly in the agora. Numerous images of lesser deities and heroes are also found throughout the city.

Paul responds to the rampant idolatry by preaching the gospel first in the local Jewish synagogue. There, Paul encounters both religious Jews and devout Gentile God-fearers. Both groups would be biblically literate. Paul also preaches in the busy Athens marketplace (called the agora) to the biblically illiterate Gentiles of Athens.

While Paul is speaking in the agora, Epicurean and Stoic philosophers overhear and engage him in conversation. Evidently, they do not understand much of what Paul is saying because they insult him by calling him a “babbler.” They seem to think that he is talking about two new foreign gods: Jesus and Resurrection. The Greek word for resurrection is anastasis, and they misunderstood Paul to be talking about a goddess named Anastasis.

Epicureanism and Stoicism are two of the more popular philosophical schools of the first-century Roman world. The Stoics were more popular with the common people. John Polhill, in [amazon_textlink asin=’0805401261′ text=’vol. 26, Acts, The New American Commentary‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’9a4661e1-86ac-11e7-8e11-e13cbf06a3af’], describes the beliefs of these two schools:

Epicureans were thoroughgoing materialists, believing that everything came from atoms or particles of matter. There was no life beyond this; all that was human returned to matter at death. Though the Epicureans did not deny the existence of gods, they saw them as totally indifferent to humanity. They did not believe in providence of any sort; and if one truly learned from the gods, that person would try to live the same sort of detached and tranquil life as they, as free from pain and passion and superstitious fears as they.

The Stoics had a more lively view of the gods than the Epicureans, believing very much in the divine providence. They were pantheists, believing that the ultimate divine principle was to be found in all of nature, including human beings. This spark of divinity, which they referred to as the logos, was the cohesive rational principle that bound the entire cosmic order together. Humans thus realized their fullest potential when they lived by reason. By reason, i.e., the divine principle within them which linked them with the gods and nature, they could discover ultimate truth for themselves. The Stoics generally had a rather high ethic and put great stock on self-sufficiency. Since they viewed all humans as bound together by common possession of the divine logos, they also had a strong sense of universal brotherhood.

Largely confused by what Paul is saying, the philosophers invite Paul to explain his beliefs to a council of wealthy, educated Athenians, known as the Areopagus. It is important to mention that there is also a hill in Athens named the Areopagus, but the council of that name did not always meet there. Paul may meet with them in a place called the Stoa Basilicos in the agora. The function of the council in the mid-first-century is unknown. Were they acting like a speech and debate club who were always curious to hear the latest news, or were they serving in some official capacity for the city? We don’t know.

In verses 22-31, Paul delivers a lengthy address to the assembled intellectuals of the Areopagus. These Greek philosophers are biblically illiterate, so Paul cannot possibly quote from the Hebrew Scriptures to make his case. He must use a different approach.

What Paul decides to do is find common ground with the Stoics and Epicureans, and build his case from that common ground. Paul first compliments the religiosity of the people of Athens by noting the numerous objects of worship scattered throughout the city. One altar stood out for Paul. The altar read, “To the unknown god.”

Why would the Athenians build an altar to an unknown god? Craig Keener reports, “During a plague long before Paul’s time, no altars had successfully propitiated the gods; Athens had finally offered sacrifices to an unknown god, immediately staying the plague. These altars were still standing, and Paul uses them as the basis for his speech.”

Assuming that the Athenians would want to know the identity of this unknown god which stayed the plague all those years ago, Paul introduces the Judeo-Christian God. This God is the creator of the world and everything in it. He is not confined to temples made by humans, meaning He transcends the physical world. Human beings cannot give this God anything, for He is completely self-sufficient and self-existent. This Creator-God gives to people their very lives. These concepts are at least somewhat familiar to the Greek intellectuals of the Areopagus. Thus, Paul has started on a common foundation that he can now build upon.

Paul next explains that all of mankind is descended from one man whom God created. He is, of course, talking about Adam, but he doesn’t mention his name here. From this one man, God determined the nations’ time periods and geographical boundaries. In other words, God has been completely sovereign over human history. What was God’s purpose in directing the timing and boundaries of the nations? To enable humanity to seek Him and find Him.

Theologian William Lane Craig believes that Acts 17:26-27 provides evidence for the idea that God has planned all human history to maximize the number of people that would come to know Him. On the Reasonable Faith website, in the article “Where was God?”, Craig writes:

I think that as Christians we want to say that God is providentially directing a world of free creatures in such a way as to maximize the number of persons to come to know him freely and to bring them into his Kingdom. And from the very creation of man, God was known by man at first. Adam and Eve and their children knew God. The Scripture says that God’s existence and nature is evident in the creation around us and that his moral law is written on our hearts. So from time immemorial people have known of the existence of God and of his moral demands on us. . . .

According to Paul [in Acts 17], the whole development of the human race is under the providence of God with a goal toward achieving the maximal knowledge of God. I think we see the marvelous plan of God unfolded in human history.

Paul then argues that God is not far from any person, and he quotes Greek poets (Epimenides and Aratus), with which the Areopagus would be familiar, to bolster his contention. The poet Aratus wrote that “we are all truly [Zeus’] offspring,” but Paul co-opts this quote to teach a lesson about the Judeo-Christian God. If we are the offspring of the Creator God, then we ought not to think that our Creator could be in the form of an idol made of gold, silver, or stone. Whoever created us must be greater than us, not lesser. The cause must be greater than the effect.

In verse 30-31, Paul reaches the climax of his speech. Up until now, God has overlooked the ignorance of mankind, the failure of men and women to find Him. This would hit the Athenians between the eyes because they considered themselves to be highly educated and knowledgeable, yet here was Paul telling them that they were ignorant of the true God.

God is now commanding everyone to repent of their ignorance. Why? Because God has appointed a day of judgment in the future for all humankind. God has appointed a man to do the judging on that day, and God confirmed this appointment by raising this man from the dead.

At this point in his speech, Paul seems to be interrupted by the reaction of the Areopagus. The mention of a bodily resurrection splits the crowd three ways. The first group mocks him. The second group asks to hear more from Paul. The third group eventually becomes believers, and two of these believers are named: Dionysius the Areopagite and a woman named Damaris. Damaris would likely not have been part of the Areopagus, but she must have overheard Paul or she must have been associated with someone on the Areopagus.

Notice that Paul sticks to the fundamentals when he evangelizes the Athenian audience. Darrell Bock, in [amazon_textlink asin=’0801026687′ text=’Acts, Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’183b416a-86ad-11e7-9851-81f93c8cd066′], summarizes Paul’s presentation about God:

He is creator, sustainer of life, and thus sovereign over the nations and the Father of us all. For all the disputation over creation and how it took place, the most fundamental truth is that God is the creator of life and we are God’s creatures, responsible to him. This means that God is, and has the right to be, our judge, something our world seeks to avoid acknowledging.