Post Author: Bill Pratt

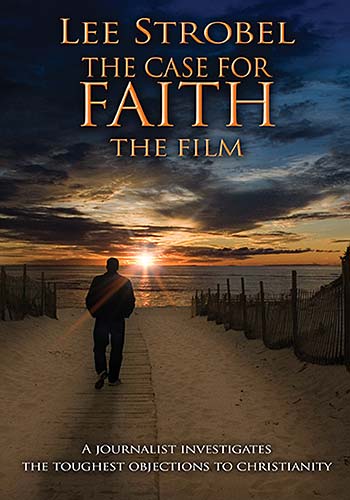

Last night I watched the DVD, The Case for Faith, featuring Lee Strobel.  The video deals with two issues from the book that bears the same name: 1) How can Jesus be the only way? and 2) How can God exist and there be so much evil, pain, and suffering?

The video deals with two issues from the book that bears the same name: 1) How can Jesus be the only way? and 2) How can God exist and there be so much evil, pain, and suffering?

In the DVD, Strobel features the words of Charles Templeton prominently and lets his challenges to the Christian faith drive the discussion. Templeton, if you recall, was a co-evangelist with Billy Graham back in the 1940’s. Templeton suffered a crisis of faith and eventually turned his back on Christianity. Strobel interviewed Templeton for his book, The Case for Faith, which quickly became a Christian apologetics classic.

The DVD answers these tough questions by interviewing some of Christianity’s greatest living apologists and scholars. Some of those who participated were Craig Hazen, Greg Koukl, J. P. Moreland, N. T. Wright, Ben Witherington, and Peter Kreeft. I may be leaving some out, but those are the ones that come to mind.

Along with these scholars, the film also features the stories of two people who suffered greatly, and how their suffering affected their relationship with God. These stories are truly powerful and balance the documentary between intellectual arguments and heart-felt experience.

All in all, I highly commend this DVD to all Christians who have ever thought about these two key issues and to skeptics who are open to hearing for themselves from some of Christianity’s best and brightest. This DVD was truly fantastic. I regret waiting so long to see it.