Jesus is teaching and, within the crowd, an expert in the Old Testament stands up to challenge him. He asks Jesus a common question among Jews of the day: What do I do to guarantee I will be accepted into the kingdom of God when the end of the age arrives?

Jesus is teaching and, within the crowd, an expert in the Old Testament stands up to challenge him. He asks Jesus a common question among Jews of the day: What do I do to guarantee I will be accepted into the kingdom of God when the end of the age arrives?

This question most likely references the description of the end times in Daniel 12:2. Daniel wrote, “Multitudes who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake: some to everlasting life, others to shame and everlasting contempt.” The lawyer wants to see how Jesus will answer this question, probably hoping to catch Jesus in an error.

Jesus turns the question back on the lawyer and asks the lawyer what his reading of the Law is on this important subject. The lawyer quotes Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18, which effectively command a person to love God and love his neighbor. Jesus commends the lawyer for his answer. Robert H. Stein, in vol. 24, Luke, The New American Commentary, provides some interesting background:

The expert’s answer consisted of two OT passages. The first (Deut 6:5) was called the Shema because it begins ‘Hear, O Israel.’ A devout Jew would repeat it twice each day (Ber. 1:1–4). In the Shema three prepositional phrases describe the total response of love toward God. These involve the heart (emotions), the soul (consciousness), and strength (motivation). The Synoptic Gospels all have ‘heart’ and ‘soul,’ Matthew omits strength, and all add ‘mind’ (intelligence). The second OT passage in the lawyer’s answer is Lev 19:18. It is found also in Rom 13:9; Gal 5:14; and Jas 2:8. In Luke the two OT passages are combined into a single command, whereas in Mark 12:31; Matt 22:39 they are left separate. Whether these two OT passages were linked before Jesus’ time is uncertain. They appear together in the early Christian literature. That this twofold summary was basic to Jesus’ teaching is evident by its appearance in his parables (Luke 15:18, 21; 18:2; cf. also 11:42, where ‘justice’ equals ‘love your neighbor’).

Some Christians mistakenly believe that Jesus is advocating a salvation by works in this passage, but the commands to love God and love your neighbor are completely compatible and consistent with salvation by grace through faith in Jesus Christ. Stein expands on this topic:

To love God means to accept what God in his grace has done and to trust in him. Faith involves more than mental assent to theological doctrines. Similarly, love is not just an emotion. Both entail an obedient trust in the God of grace and mercy. The response of love to God and of faith in God are very much the same. This intimate association between love and faith is seen most clearly in Luke 7:47, 50. For Luke, as for Paul, salvation was by grace (Acts 13:38–39) through faith (Luke 7:50; 8:48; 17:19; 18:42), but this faith works through love (see Gal 5:6). At times the aspect of faith may need to be emphasized and at other times love.

Theologian Norman Geisler reminds us, in Systematic Theology, Volume Three: Sin, Salvation, that

True faith involves love, which is the greatest commandment: ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind’ (Matt. 22:37). Unbelievers ‘perish because they refused to love the truth and so be saved’ (2 Thess. 2:10). Paul speaks of ‘faith working through love’ (Gal. 5:6).

The lawyer, however, demands clarification from Jesus on who exactly counts as a neighbor. Instead of giving the lawyer a direct answer, Jesus delivers a parable. In brief, a Jew traveling alone from Jerusalem to Jericho is accosted by robbers and left for dead. An Aaronic priest and a Levite both pass him by without helping, but a Samaritan stops to help him. The Samaritan also transports him to an inn and pays for him to stay several weeks until he heals.

The road from Jerusalem to Jericho was remote and dangerous. It was a 3,000 feet descent along a 17- mile road. There were plenty of places for robbers to hide.

Once the man is beaten, robbed, and left for dead, a temple priest (a descendant of Aaron) happens by. Why did the priest fail to help the man? Leon Morris, in vol. 3, Luke: An Introduction and Commentary, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries, speculates:

Since the man was ‘half dead’ the priest would probably not have been able to be certain whether he was dead or not without touching him. But if he touched him and the man was in fact dead, then he would have incurred the ceremonial defilement that the Law forbade (Lev. 21:1ff.). He could be sure of retaining his ceremonial purity only by leaving the man alone. He could be sure he was not omitting to help a man in need only by going to him. In this conflict it was ceremonial purity that won the day. Not only did he not help, he went to the other side of the road. He deliberately avoided any possibility of contact.

A man from the tribe of Levi then comes upon the man, but he also continues without helping him. Robert Stein explains:

The Levite was a descendant of Levi who assisted the priests in various sacrificial duties and policing the temple but could not perform the sacrificial acts. Luke was not suggesting that since the Levite’s duties were inferior to those of a priest he might have been more open to help because the problem of becoming defiled was less acute. Rather he was emphasizing that neither the wise and understanding (10:21) nor the proud and ruling (1:51–52) practice being loving neighbors.

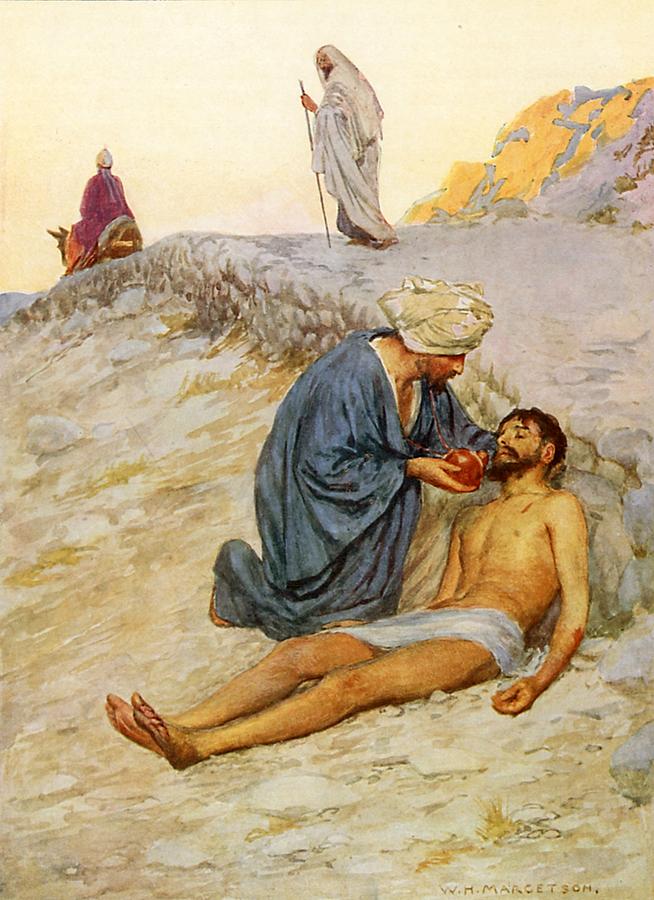

Finally, a Samaritan man arrives and has compassion on the injured Jew. He binds his wounds and treats them with wine and oil. Wine was used for cleaning wounds, due to the alcohol in it, and the oil was used to provide pain relief.

The Samaritan goes even further, though. He places the man on his donkey and carries him to an inn where he can rest and heal. He offers enough money to the innkeeper for the man to be able to stay for several weeks.

The fact that Jesus uses a Samaritan as the hero in the parable is shocking to his audience. It is worthwhile to remind the reader of the history between the Jews and Samaritans. Stein writes:

The united kingdom was divided after Solomon’s death due to the foolishness of his son, Rehoboam (1 Kgs 12). The ten northern tribes formed a nation known variously as Israel, Ephraim, or (after the capital city built by Omri) Samaria. In 722 b.c. Samaria fell to the Assyrians, and the leading citizens were exiled and dispersed throughout the Assyrian Empire. Non-Jewish peoples were then brought into Samaria. Intermarriage resulted, and the ‘rebels’ became ‘half-breeds’ in the eyes of the Southern Kingdom of Judea. (Jews comes from the term Judea.) After the Jews returned from exile in Babylon, the Samaritans sought at first to participate in the rebuilding of the temple. When their offer of assistance was rejected, they sought to impede its building (Ezra 4–6; Neh 2–4). The Samaritans later built their own temple on Mount Gerizim, but led by John Hyrcanus the Jews destroyed it in 128 b.c. (cf. John 4:20–21). So great was Jewish and Samaritan hostility that Jesus’ opponents could think of nothing worse to say of him than, ‘Aren’t we right in saying that you are a Samaritan and demon-possessed?’ (John 8:48; cf. also 4:9).

When Jesus finishes the parable, he asks the lawyer who was the true neighbor to the Jew who had been robbed. The lawyer, without being able to say the word “Samaritan,” nevertheless identifies the Samaritan as the true neighbor.

The message is clear. The command to love our neighbor crosses ethnic, religious, and national boundaries. Stein comments:

For most Jews a neighbor was another Jew, not a Samaritan or a Gentile. The Pharisees (John 7:49) and the Essenes did not even include all Jews (1QS 1:9–10). The teaching of the latter stands in sharp contrast with that of Jesus.

Jesus commands us to love everyone as we love ourselves, including those whom we consider our enemies.