We know that evil cannot exist without good. We know that evil is not the opposite of good, like yin and yang. But what exactly is evil?

We know that evil cannot exist without good. We know that evil is not the opposite of good, like yin and yang. But what exactly is evil?

Philosopher David Oderberg answers this question in an article entitled “The Metaphysics of Privation.” Oderberg first explains that evil is the absence of good.

But what is good? Oderberg writes that good is “a kind of fulfillment, the completion of some tendency of a thing.” If good is the fulfillment of a thing, then evil is the lack, or privation, of that fulfillment. Oderberg expands on the meaning of privation:

It is the absence of something on which some aspect of the world has what we might call a prior claim or title but where the claim or title need not be construed evaluatively. So, for example, if you have cooked me dinner, and I ask for a third helping of ice cream but you cannot give me any because you’ve run out, then in the technical sense of privation used here, my inability to have more ice cream is a privation, not a mere absence, because I had a prior desire for it.

The privation becomes an evaluative matter when we ask, say, whether I really need a third helping; since I don’t, I haven’t been deprived of it, in the evaluative sense, though I am still subject technically to a privation as opposed to a mere absence. The latter would be the case if you served me cheese for dessert and, without even a thought on either of our parts about ice cream, in fact I did not eat ice cream but cheese.

So your inability to have more ice cream when you want more ice cream is a privation, but it is not necessarily evil. What makes a privation evil?

[W]ithin privations there are those that are essentially evaluative and those that are not. Deafness and disease are privations we correctly regard as bad or evil. The essentially evaluative privations are, precisely, the evils. What they have in common is that they are all privations of good. Since – I am assuming – good is a kind of fulfillment evil is the privation of a kind of fulfillment. The relevant kind of fulfillment belongs to the nature of a thing – how it is supposed to function given the kind of thing it is.

Given that evil is privation of the good, Oderberg, after further analysis, concludes with three propositions about evil (actually there are five, but space does not permit me to deal with the last two).

1. Evil is real. By real, Oderberg is denying that evil is illusory or unreal, a position pantheists take.

2. Evil is a privation. As we discussed above, evil is a lack of good.

3. Privations are not real. What Oderberg means by this proposition is that evil is not a real thing like the computer I am typing on is a real thing, or the cup of tea I am sipping is a real thing. But privations are real in the sense that they have cognitive being. They really exist in the minds of intellectual beings. Privations are beings of reason.

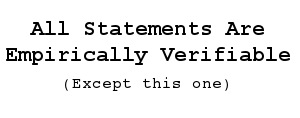

It’s been a while since we’ve beat up scientism on the blog, so I figured we were due again. It’s an “ism” that just keeps rearing its head over and over and thus needs to be slapped around over and over. Philosopher Edward Feser, in

It’s been a while since we’ve beat up scientism on the blog, so I figured we were due again. It’s an “ism” that just keeps rearing its head over and over and thus needs to be slapped around over and over. Philosopher Edward Feser, in