Some Bible scholars believe that the Book of Jonah is a fictional tale written purely for teaching purposes by its original author. They argue that the original author never meant for the story to be taken as real history. While it may be impossible to know just based on the contents of the book itself, there is one important person who seems to have considered the events in Jonah to be historical: Jesus Christ.

Some Bible scholars believe that the Book of Jonah is a fictional tale written purely for teaching purposes by its original author. They argue that the original author never meant for the story to be taken as real history. While it may be impossible to know just based on the contents of the book itself, there is one important person who seems to have considered the events in Jonah to be historical: Jesus Christ.

Billy K. Smith and Franklin S. Page write, in Amos, Obadiah, Jonah: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture (The New American Commentary):

Finally, there is the witness of Jesus Christ, which apparently was the basis for the early church’s linking the historicity of Jonah’s experience with that of Jesus, especially his resurrection. Although it would be conceivable that Jesus might have been merely illustrating in Matt 12:40 when he associated his prophesied resurrection with Jonah’s experience in the fish, it is much more difficult to deny that Jesus was assuming the historicity of the conversion of the Ninevites when he continued in v. 41 (cf. Luke 11:32).

‘The men of Nineveh will stand up at the judgment with this generation and condemn it; for they repented at the preaching of Jonah, and now one greater than Jonah is here.’

This is confirmed in the following verse (cf. Luke 11:33) when Jesus parallels the ‘men of Nineveh’ with the ‘Queen of the South,’ whose visit to Jerusalem is recounted in 1 Kings.

‘The Queen of the South will rise at the judgment with this generation and condemn it; for she came from the ends of the earth to listen to Solomon’s wisdom, and now one greater than Solomon is here.’

Clearly Jesus did not see Jonah as a parable or an allegory. As J. W. McGarvey stated long ago, ‘It is really a question as to whether Jesus is to be received as a competent witness respecting historical and literary matters of the ages which preceded His own.’

Norman Geisler and Thomas Howe, in When Critics Ask: A Popular Handbook on Bible Difficulties, add:

[T]he most devastating argument against the denial of the historical accuracy of Jonah is found in Matthew 12:40. In this passage Jesus predicts His own burial and resurrection, and provides the doubting scribes and Pharisees the sign that they demanded. The sign is the experience of Jonah. Jesus says, ‘For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.’ If the tale of Jonah’s experience in the belly of the great fish was only fiction, then this provided no prophetic support for Jesus’ claim. The point of making reference to Jonah is that if they did not believe the story of Jonah being in the belly of the fish, then they would not believe the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus. As far as Jesus was concerned, the historical fact of His own death, burial, and resurrection was on the same historical ground as Jonah in the belly of the fish. To reject one was to cast doubt on the other (cf. John 3:12). Likewise, if they believed one, they should believe the other. . . .

Jesus went on to mention the significant historical detail. His own death, burial, and resurrection was the supreme sign that verified His claims. When Jonah preached to the unbelieving Gentiles, they repented. But, here was Jesus in the presence of His own people, the very people of God, and yet they refused to believe. Therefore, the men of Nineveh would stand up in judgment against them, ‘because they [the men of Nineveh] repented at the preaching of Jonah’ (Matt. 12:41). If the events of the Book of Jonah were merely parable or fiction, and not literal history, then the men of Nineveh did not really repent, and any judgment upon the unrepentant Pharisees would be unjust and unfair. Because of the testimony of Jesus, we can be sure that Jonah records literal history.

The NT writers quote the OT hundreds of times, yet they never once quote from the Book of Ecclesiastes. Doesn’t this indicate that the NT writers did not consider the book to be inspired by God?

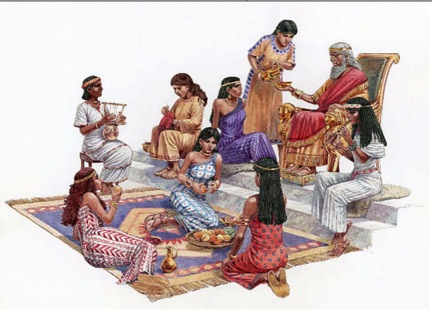

The NT writers quote the OT hundreds of times, yet they never once quote from the Book of Ecclesiastes. Doesn’t this indicate that the NT writers did not consider the book to be inspired by God? In 1 Kings 11, verse 3, we read that Solomon, the king who ruled at the pinnacle of Israelite power, had 700 wives and 300 concubines. Other great men of the Old Testament also had more than one wife. Are we to conclude that God encourages polygamy?

In 1 Kings 11, verse 3, we read that Solomon, the king who ruled at the pinnacle of Israelite power, had 700 wives and 300 concubines. Other great men of the Old Testament also had more than one wife. Are we to conclude that God encourages polygamy? According to the Bible, an angel created by God (Satan or Lucifer) was the first creature to bring evil into the universe. But the question arises how this good creature, created by a good God, living in a good universe, could choose evil. God did not cause Satan to sin, so who caused Satan to sin?

According to the Bible, an angel created by God (Satan or Lucifer) was the first creature to bring evil into the universe. But the question arises how this good creature, created by a good God, living in a good universe, could choose evil. God did not cause Satan to sin, so who caused Satan to sin?