Post Author: Bill Pratt

In part 1 of this series, Walt Tucker gave an explanation of the two slit experiment and its relation to quantum mechanics. In part 2, Walt explains why this experiment does not violate the law of non-contradiction. Below are Walt’s words.

The quick answer is: if a particle could actually be observed as A and not A at the same time, that would violate the law of non-contradiction. Since that cannot be done, even in the quantum world, there is no violation!

Quantum superposition is the mathematical addition of probability densities of all of the possible states of a quantum system. The result of the superposition of the densities is used to calculate the probability of observing the system in one of the states. In a binary probability space there is a chance that a quantum event can be observed as A or as not A.

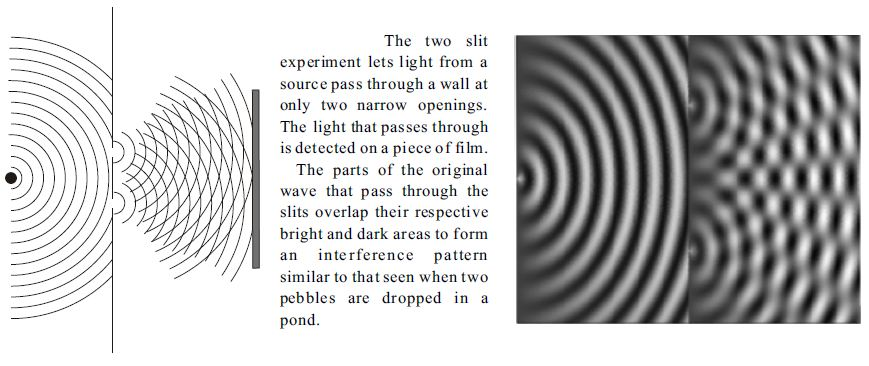

In the two slit experiment, it is the probability of a photon going through slit A or slit B. Slit B would be not A. When you don’t observe the slits to know which slit the particle went through, you find that it goes through both. So, this guy is saying that both A and not A exist simultaneously and the law of non-contradiction is violated. But that is not exactly the case!

When the quantum system is observed, it is observed in the context of a particle with specific location and it can only be A or not A, it can’t be both. But when the system is not being observed, it is not in the form of a point like particle, it is in a wave form where the quanta of energy is spread across the possible states as a wave. It is in the wave form until it is observed. The observation collapses the wave to a point like particle where the law of non-contradiction is also observed (like popping a whole balloon by a pin at only one point on the surface of the balloon).

One could say the law of non-contradiction is only valid in the world of observables (the world in which we interact). But it can also be said that since the energy is in a wave form when it is not being observed, that it is not true that it is A and not A at the same time, but that it is something else, a wave, that only has the potential to be either A or not A once it is observed. In other words, it is a whole other form that makes no sense in terms of A and non-A.

It is like saying a potato is mashed potatoes, French fries, and a baked potato all at the same time, when it is not any of them when it is a potato in the garden. The potato has the potential to be any of those forms of potato, but isn’t any of them until one takes the potato and does something with it. The same thing applies in the quantum world. A wave has the potential to be observed at slit A or slit B (since a quanta of energy must be observed at one point), but while it is still a wave, it cannot be observed at both slits at the same time because an observation would cause it to no longer be a wave, but a particle.

Bottom line is that having the potential to be one thing or another does not violate the law of non-contradiction. If the particle could actually be observed as A and not A at the same time, then there would be a violation of the law of non-contradiction!

[Bill Pratt] Thanks for the explanation, Walt. Great stuff.

I’ve been reading physicist Edgar Andrews’ book

I’ve been reading physicist Edgar Andrews’ book  Some skeptics of Christianity are known to argue that the great success of science revealing the physical mechanisms of the universe should lead us to conclude that the God hypothesis is totally unnecessary. Science will ultimately reveal the laws of nature, and once we know these laws, the need for God has vanished. Does that follow?

Some skeptics of Christianity are known to argue that the great success of science revealing the physical mechanisms of the universe should lead us to conclude that the God hypothesis is totally unnecessary. Science will ultimately reveal the laws of nature, and once we know these laws, the need for God has vanished. Does that follow? The Galileo affair has often been put to work to demonstrate that religion has always been at war with science. But what really happened to Galileo? Does what happened to him prove that religion – Christianity in particular – has always been in conflict with science?

The Galileo affair has often been put to work to demonstrate that religion has always been at war with science. But what really happened to Galileo? Does what happened to him prove that religion – Christianity in particular – has always been in conflict with science?