Not according to Jehovah’s Witnesses, who believe that Jesus is not God, but the archangel Michael. Norman Geisler and Ron Rhodes frame the issue well in their book When Cultists Ask: A Popular Handbook on Cultic Misinterpretations.

In John 8:58 (nasb) we read, ‘Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, before Abraham was born, I am.”’ By contrast, the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ New World Translation reads, ‘Jesus said to them: “Most truly I say to you, Before Abraham came into existence, I have been.”’ This indicates that Jesus was preexistent but not eternally preexistent (certainly not as the great I Am of the Old Testament).

Has the Watchtower Society (Jehovah’s Witnesses) correctly translated verse 58? Have Christians been misunderstanding this verse for two thousand years? Geisler and Rhodes explain:

Greek scholars agree that the Watchtower Society has no justification for translating ego eimi in John 8:58 as ‘“I have been’ (a translation that masks its connection to Exodus 3:14 where God reveals his name to be I Am). The Watchtower Society once attempted to classify the Greek word eimi as a perfect indefinite tense to justify this translation—but Greek scholars have responded by pointing out that there is no such thing as a perfect indefinite tense in the Greek.

The words ego eimi occur many times in John’s Gospel. Interestingly, the New World Translation elsewhere translates ego eimi correctly (as in John 4:26; 6:35, 48, 51; 8:12, 24, 28; 10:7, 11, 14; 11:25; 14:6; 15:1, 5; and 18:5, 6, 8). Only in John 8:58 does the mistranslation occur. The Watchtower Society is motivated to translate this verse differently in order to avoid it appearing that Jesus is the great I Am of the Old Testament. Consistency and scholarly integrity calls for John 8:58 to be translated the same way as all the other occurrences of ego eimi—that is, as ‘I am.’

Finally, as noted above, I Am is the name God revealed to Moses in Exodus 3:14–15. The name conveys the idea of eternal self-existence. Yahweh never came into being at a point in time, for he has always existed. To know Yahweh is to know the eternal one. It is therefore understandable that when Jesus made the claim to be I Am, the Jews immediately picked up stones with the intention of killing Jesus, for they recognized he was implicitly identifying himself as Yahweh.

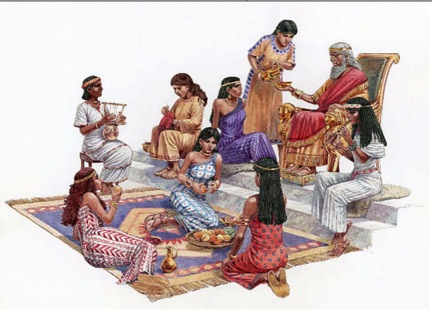

In 1 Kings 11, verse 3, we read that Solomon, the king who ruled at the pinnacle of Israelite power, had 700 wives and 300 concubines. Other great men of the Old Testament also had more than one wife. Are we to conclude that God encourages polygamy?

In 1 Kings 11, verse 3, we read that Solomon, the king who ruled at the pinnacle of Israelite power, had 700 wives and 300 concubines. Other great men of the Old Testament also had more than one wife. Are we to conclude that God encourages polygamy? Some Bible scholars believe that the Book of Jonah is a fictional tale written purely for teaching purposes by its original author. They argue that the original author never meant for the story to be taken as real history. While it may be impossible to know just based on the contents of the book itself, there is one important person who seems to have considered the events in Jonah to be historical: Jesus Christ.

Some Bible scholars believe that the Book of Jonah is a fictional tale written purely for teaching purposes by its original author. They argue that the original author never meant for the story to be taken as real history. While it may be impossible to know just based on the contents of the book itself, there is one important person who seems to have considered the events in Jonah to be historical: Jesus Christ.