From the birth of Jesus to the beginning of Matthew 3, we skip about thirty years. John the Baptist’s ministry started between the years AD 26 and 28, so we would expect the events recorded in chapter three of Matthew to take place after John’s ministry had been established for a year or two.

From the birth of Jesus to the beginning of Matthew 3, we skip about thirty years. John the Baptist’s ministry started between the years AD 26 and 28, so we would expect the events recorded in chapter three of Matthew to take place after John’s ministry had been established for a year or two.

John’s message is simple: turn away from your sins (repent) so that you are prepared for the inauguration of God’s kingdom on earth. Matthew quotes Isaiah 40:3 to show that John is the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy. John is the voice crying out in the wilderness.

Verse 4 connects John to the ministry of Elijah, for John dresses as Elijah did. They are both wilderness prophets who are poor and humble. Michael Wilkins, in Matthew, Mark, Luke: Volume One of Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary, writes:

Locusts and wild honey were not an unusual diet for people living in the desert. The locust is the migratory phase of the grasshopper and was allowable food for the people of Israel to eat, as opposed to other kinds of crawling and flying insects (Lev. 11:20–23). They are an important food source in many areas of the world, especially as a source of protein, because even in the most desolate areas they are abundant. They are often collected, dried, and ground into flour. Protein and fat were derived from locusts, while sugar came from the honey of wild bees.

Verses 5-6 indicate that John is attracting large crowds to the Jordan River where he is preaching. The crowds would come to confess their sins and be baptized by John. Craig Blomberg, in vol. 22, Matthew, The New American Commentary, explains about baptism that

Jews seem regularly to have practiced water baptism by immersion for adult proselytes from pagan backgrounds as an initiation into Judaism. Qumran commanded ritual bathing daily to symbolize repeated cleansing from sin. But John’s call for a one-time-only baptism for those who had been born as Jews was unprecedented. John thus insisted that one’s ancestry was not adequate to ensure one’s relationship with God. As has often been put somewhat colloquially, ‘God has no grandchildren.’ Our parents’ religious affiliations afford no substitute for our own personal commitment (cf. v. 9).

The crowds coming to see John included members of two religio-political organizations, the Sadducees and Pharisees. Together, these two groups composed most of the membership of the Jewish Supreme Court, known as the Sanhedrin. Michael Wilkins provides some historical background on the identities of these two groups.

The name Pharisee is probably derived from the Hebrew/Aramaic perušim, the separated ones, alluding to both their origin and their characteristic practices. They tended to be politically conservative and religiously liberal and held the minority membership on the Sanhedrin.

They held to the supreme place of Torah, with a rigorous scribal interpretation of it. Their most pronounced characteristic was their adherence to the oral tradition, which they obeyed rigorously as an attempt to make the written law relevant to daily life. They had a well-developed belief in angelic beings. They had concrete messianic hopes, as they looked for the coming Davidic messianic kingdom. The Messiah would overthrow the Gentiles and restore the fortunes of Israel with Jerusalem as capital. They believed in the resurrection of the righteous when the messianic kingdom arrived, with the accompanying punishment of the wicked. They viewed Rome as an illegitimate force that was preventing Israel from experiencing its divinely ordained role in the outworking of the covenants. They held strongly to divine providence, yet viewed humans as having freedom of choice, which ensures their responsibility. As a lay fellowship or brotherhood connected with local synagogues, the Pharisees were popular with the common people.

The Sadducees were a small group with aristocratic and priestly influence, who derived their authority from the activities of the temple. They tended to be politically liberal and religiously conservative and held the majority membership on the Sanhedrin.

They held a conservative attitude toward the Scriptures, accepting nothing as authoritative except the written word, literally interpreted. They accepted only Torah (the five books of Moses) as authoritative, rejecting any beliefs not found there. For that reason they denied the resurrection from the dead, the reality of angels, and spirit life. They produced no literature of which we are aware. They had no expressed messianic expectation, which tended to make them satisfied with their wealth and political power. They were open to aspects of Hellenism and often collaborated with the Romans. They tended to be removed from the common people by economic and political status.

When John sees the Pharisees and Sadducees, he accuses them of being the offspring (brood) of poisonous snakes. They are shrewd and dangerous. Why does John accuse them of this? He perceives that they are only pretending to be interested in John’s message. In reality, they do not think they need to repent of anything.

In their way of thinking, they are descendants of Abraham, and therefore God automatically accepts them as His own. John corrects their faulty theology and forcefully asserts that God can make even stones His children if He so desires. The true children of God will repent of their sins and then lead lives of good works and righteousness. The people of Israel (the root of the trees), and especially the Jewish leadership, will be judged by God based on this criteria, not whether they are physical descendants of Abraham.

Starting in verse 11, John then speaks of the One who would do the judging. The One who is coming, the Messiah, is so mighty that John doesn’t even qualify to be His slave (slaves would carry the sandals of their masters). The Messiah, unlike John, will baptize with the Holy Spirit and with fire. Louis A. Barbieri, in The Bible Knowledge Commentary, writes:

Those hearing John’s words would have been reminded of two Old Testament prophecies: Joel 2:28–29 and Malachi 3:2–5. Joel had given the promise of the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on Israel. An actual outpouring of the Spirit did occur in Acts 2 on the day of Pentecost, but experientially Israel did not enter into the benefits of that event. She will yet experience the benefits of this accomplished work when she turns in repentance at the Lord’s Second Advent. The baptism ‘with fire’ referred to the judging and cleansing of those who would enter the kingdom, as prophesied in Malachi 3.

In verse 12, Blomberg explains, “John uses the image of a farmer separating valuable wheat from worthless chaff by throwing the grain into the air and allowing the two constituent elements to separate in the wind. The wheat, like believers, is preserved and safeguarded; the chaff, like unbelievers, is destroyed.”

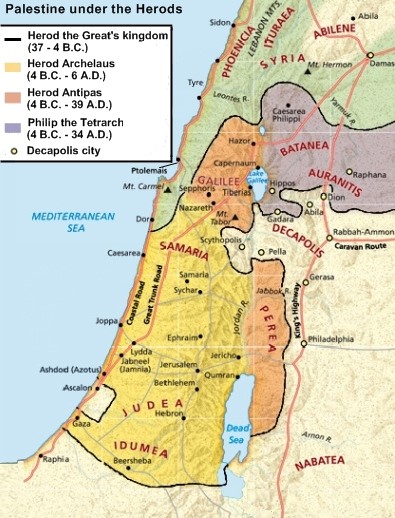

In verses 13-17, Matthew records the official inauguration of the Kingdom of God on earth, the baptism of Jesus. Jesus travels south from Galilee to Judea to be baptized by John. John is confused by Jesus’s request because Jesus (the promised Messiah) should have no need of repentance and confession of sins, of which John’s baptism is symbolic.

Jesus insists that He be baptized by John because His baptism, firstly, authenticates John’s ministry as Jesus’s forerunner, and, secondly, officially marks the beginning of Jesus’s public ministry. After Jesus is baptized, the Holy Spirit descends on Jesus (John uses the metaphor of a dove) and God the Father speaks the following words: “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased.” Blomberg adds:

The heavenly voice cites excerpts of Ps 2:7 and Isa 42:1. Both texts were taken as messianic by important segments of pre-Christian Judaism (see 4QFlor 10–14 and Tg. Isa 42:1, respectively). Together they point out Jesus’ role as both divine Son and Suffering Servant, a crucial combination for interpreting Jesus’ self-understanding and mission.