Post Author: Bill Pratt

Contemporary Jesus mythicists like Richard Carrier, Robert Price, and Earl Doherty have argued that Jesus, as a historical figure, never really existed. They, however, are hardly the first to make this claim.

Contemporary Jesus mythicists like Richard Carrier, Robert Price, and Earl Doherty have argued that Jesus, as a historical figure, never really existed. They, however, are hardly the first to make this claim.

Biblical scholar Robert Van Voorst, in his book Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence, traces the historical development of Jesus mythicism from the 1700’s in Europe. It is fascinating to see how this movement began. According to Van Voorst,

At the end of the eighteenth century, some disciples of the radical English Deist Lord Bolingbroke began to spread the idea that Jesus had never existed. Voltaire, no friend of traditional Christianity, sharply rejected such conclusions, commenting that those who deny the existence of Jesus show themselves “more ingenious than learned.”

Nevertheless, in the 1790s a few of the more radical French Enlightenment thinkers wrote that Christianity and its Christ were myths. Constantin-François Volney and Charles François Dupuis published books promoting these arguments, saying that Christianity was an updated amalgamation of ancient Persian and Babylonian mythology, with Jesus a completely mythological figure.

These ideas, however, did not seem to gain much traction until another gentleman, Bruno Bauer, came on the scene in the mid-1800’s to further the arguments.

Bauer was the most incisive writer in the nineteenth century against the historicity of Jesus. In a series of books from 1840 to 1855, Bauer attacked the historical value of the Gospel of John and the Synoptics, arguing that they were purely inventions of their early second-century authors. As such, they give a good view of the life of the early church, but nothing about Jesus.

Bauer’s early writings tried to show that historical criticism could recover the main truth of the Bible from the mass of its historical difficulties: that human self-consciousness is divine, and the Absolute Spirit can become one with the human spirit. Bauer was the first systematically to argue that Jesus did not exist. Not only do the Gospels have no historical value, but all the letters written under the name of Paul, which could provide evidence for Jesus’existence, were much later fictions. Roman and Jewish witnesses to Jesus were late, secondary, or forged.

With these witnesses removed, the evidence for Jesus evaporated, and Jesus with it. He became the product, not the producer, of Christianity. Christianity and its Christ, Bauer argued, were born in Rome and Alexandria when adherents of Roman Stoicism, Greek Neo-Platonism and Judaism combined to form a new religion that needed a founder.

How can Bauer’s arguments be summarized? Van Voorst explains that

Bauer laid down the typical threefold argument that almost all subsequent deniers of the existence of Jesus were to follow (although not in direct dependence upon him). First, he denied the value of the New Testament, especially the Gospels and Paul’s letters, in establishing the existence of Jesus. Second, he argued that the lack of mention of Jesus in non-Christian writings of the first century shows that Jesus did not exist. Neither do the few mentions of Jesus by Roman writers in the early second century establish his existence. Third, he promoted the view that Christianity was syncretistic and mythical at its beginnings.

Obviously Bauer’s arguments were highly controversial. How did academia and church authorities respond to him?

Bauer’s views of Christian origins, including his arguments for the nonexistence of Jesus, were stoutly attacked by both academics and church authorities, and effectively refuted in the minds of most. They gained no lasting following or influence on subsequent scholarship, especially in the mainstream.

Perhaps Bauer’s most important legacy is indirectly related to his biblical scholarship. When the Prussian government removed him from his Berlin University post in 1839 for his views, this further radicalized one of his students, Karl Marx. Marx would incorporate Bauer’s ideas of the mythical origins of Jesus into his ideology, and official Soviet literature and other Communist propaganda later spread this claim.

The ideas of Bauer, however, have obviously not died. In the next post, we’ll look at the most prolific contemporary proponent of Jesus mythicism, a man named George A. Wells.

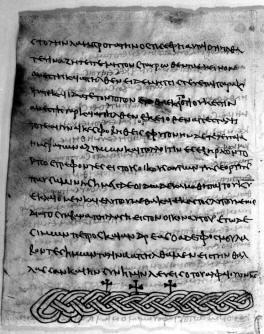

During the second through ninth centuries, a large body of Christian literature was produced that claimed (falsely) to be produced by apostles of Jesus or those close to the apostles. These works, rejected by the Church as authentic, came to be known as the New Testament Apocrypha.

During the second through ninth centuries, a large body of Christian literature was produced that claimed (falsely) to be produced by apostles of Jesus or those close to the apostles. These works, rejected by the Church as authentic, came to be known as the New Testament Apocrypha. During the second through ninth centuries, a large body of Christian literature was produced that claimed (falsely) to be produced by apostles of Jesus or those close to the apostles. These works, rejected by the Church as authentic, came to be known as the New Testament Apocrypha.

During the second through ninth centuries, a large body of Christian literature was produced that claimed (falsely) to be produced by apostles of Jesus or those close to the apostles. These works, rejected by the Church as authentic, came to be known as the New Testament Apocrypha.