The events of chapter three are hard to date, but it seems that they take place within a few years of Daniel’s interpretation of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream. Inspired by the statue in the dream, the king builds a statue which is 90 feet high, ten feet wide, and overlaid with gold. This is the height of a nine story building. The statue is built on an elevated plain outside of the ancient city of Babylon. Construction on the plain would make the statue easy to see from a long distance. J. Dwight Pentecost, in The Bible Knowledge Commentary, writes,

The events of chapter three are hard to date, but it seems that they take place within a few years of Daniel’s interpretation of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream. Inspired by the statue in the dream, the king builds a statue which is 90 feet high, ten feet wide, and overlaid with gold. This is the height of a nine story building. The statue is built on an elevated plain outside of the ancient city of Babylon. Construction on the plain would make the statue easy to see from a long distance. J. Dwight Pentecost, in The Bible Knowledge Commentary, writes,

Archeologists have uncovered a large square made of brick some six miles southeast of Babylon, which may have been the base for this image. Since this base is in the center of a wide plain, the image’s height would have been impressive. Also its proximity to Babylon would have served as a suitable rallying point for the king’s officials.

It is unclear whether the statue is made to look like Nebuchadnezzar or one of the gods of the Babylonians. It may have even been a mixture of the two. In any case, the image carved into the statue was meant to be worshiped.

When the statue is finished, Nebuchadnezzar assembles Babylonian government officials from all over the empire. There are likely hundreds of these officials brought to dedicate the image. Pentecost explains who is in attendance.

The satraps were chief representatives of the king, the prefects were military commanders, and the governors were civil administrators. The advisers were counselors to those in governmental authority. The treasurers administered the funds of the kingdom, the judges were administrators of the law, and the magistrates passed judgment in keeping with the law. The other provincial officials were probably subordinates of the satraps. This list of officers probably included all who served in any official capacity under Nebuchadnezzar.

As they are standing in front of the statue, a herald announces that when the orchestra begins to play, everyone is to bow down and worship the image Nebuchadnezzar has built. Refusal to bow down to the statue will result in execution by furnace. The furnace that had likely been used to build the statue was now acting as a death chamber.

Why would Nebuchadnezzar build this giant gold statue and then command his government officials to bow down and worship the statue? His reasoning is likely that it would unite his new empire and consolidate his authority. Iain M. Duguid, in Daniel, Reformed Expository Commentary, notes that

this act of worship was designed to reverse the consequences of the original Tower of Babel by unifying the whole world in an act of submission to this statue. When the music of a cacophony of different instruments sounded, everyone was to bow down to the statue. Sure enough, when the music rang out, ‘all the peoples, nations and men of every language fell down and worshiped the image of gold that King Nebuchadnezzar had set up’ (3:7). For a moment, the whole world was united in bowing to Nebuchadnezzar’s statue. The curse of Babel had, it seemed, successfully been reversed.

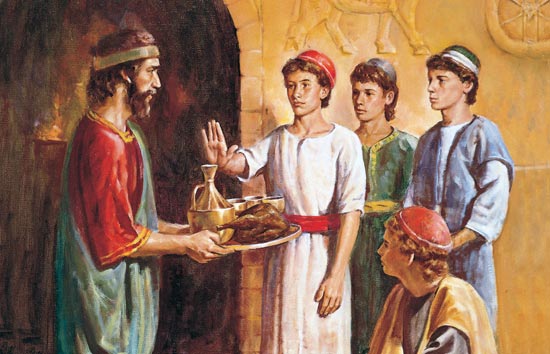

When the orchestra begins, everyone bows down except for three men – Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. Unnamed officials, who are undoubtedly jealous of the powers given to the three Jewish men, inform Nebuchadnezzar that Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego did not bow down as commanded. No mention is made of Daniel, so it seems that he was not required to attend the ceremony. He was perhaps left in the city of Babylon to administer while the rest of the government attended the dedication of the gold statue.

Nebuchadnezzar brings the three Jews before him and gives them one more chance to bow down to the statue. The three Jewish men refuse and express confidence that God will save them from the furnace, but even if He does not, they will still not worship the gods of Babylon. Duguid explains,

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego did not presume to predict what the outcome would be in their case. If God were our servant, or our accomplice, he would be predictable: he would always do our bidding. Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego understood that since God is sovereign, however, it was his choice whether he opted to be glorified in their deaths or through their dramatic deliverance. Either way, it didn’t make a difference to their decision. Whether they were miraculously delivered or left to burn in the fire, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego would not compromise their commitment to the Lord. Live or die, they would be faithful to their God.

Nebuchadnezzar orders the furnace to be heated to maximum intensity. Soldiers tie up the Jews and carry them to the opening in the top of the furnace and drop them in. The fire is so intense that the soldiers carrying the Jews are killed by the flames shooting out the top.

As Nebuchadnezzar watches at a safe distance, he is shocked at what he sees. The furnace would have an opening on the side of it where fuel could be added and ashes could be removed. As the king peers into this opening, he sees four people walking around, apparently unharmed. The fourth person appears to be some sort of divine being. The identity of this divine being could be an angel or the pre-incarnate Jesus Christ Himself. It’s impossible to know from the text.

The king approaches the furnace and orders the three Jews to come out of the opening on the side. When they step out of the furnace, they are untouched by the fire. In fact, their clothes do not even smell from the fire of the furnace.

The king, who has clearly seen a miracle, praises the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego for saving their lives. He then decrees that anyone who speaks against the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego will be executed and have their property destroyed.

Although Nebuchadnezzar has just seen a miracle, he still does not pledge his personal allegiance to Yahweh. He merely expresses respect for the God of the Jews. Why is this? Duguid offers the following analysis:

Yet even great miracles don’t have the power in themselves to change people’s hearts. People will always find a way to explain them away. So too Nebuchadnezzar’s heart was not changed at a deep level by this experience. The God of whom he spoke was still ‘the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego,’ or ‘their God,’ not his own. He still would not fall down in the face of this revelation of the Lord’s power and confess, ‘My Lord and my God.’

Sadly, there are many who respond in exactly the same way to the message of the cross and resurrection of Christ, and other demonstrations of God’s mighty power. When you tell them what the Lord has done, they say, ‘I’m glad you’ve found something that works for you. I’m happy for you. But don’t ask me to submit to your God.’ Sooner or later, though, they will be forced to bow their knee before the Lord and confess his power and his glory. Such a confession on that day will save no one: it will be a bare recognition of the nature of reality. The confession that saves is the one that bows joyfully now before the Lord and confesses him, ‘My Lord and my God, my only hope in life and death.’

Three years after Daniel is brought to Babylon (602 BC), King Nebuchadnezzar has a recurring dream. He knows the dream is significant, so he asks the wise men who serve him to interpret the dream for him. There is a catch, though. He will not tell them what he dreamed; they have to figure that out for themselves, and then interpret its meaning. The wise men complain that only the gods could possibly know his dream and that what he asks is impossible.

Three years after Daniel is brought to Babylon (602 BC), King Nebuchadnezzar has a recurring dream. He knows the dream is significant, so he asks the wise men who serve him to interpret the dream for him. There is a catch, though. He will not tell them what he dreamed; they have to figure that out for themselves, and then interpret its meaning. The wise men complain that only the gods could possibly know his dream and that what he asks is impossible. The traditional view of the book of Daniel is that it was written by Daniel or an associate of Daniel and completed around 530 BC. Some biblical scholars are skeptical that Daniel wrote the book and they attribute it to a second century BC Jew writing during the Maccabean revolt. More will be said about this in a subsequent blog post.

The traditional view of the book of Daniel is that it was written by Daniel or an associate of Daniel and completed around 530 BC. Some biblical scholars are skeptical that Daniel wrote the book and they attribute it to a second century BC Jew writing during the Maccabean revolt. More will be said about this in a subsequent blog post.