Post Author: Bill Pratt

This post is a continuation from Part 1 where we introduced the recent NOAA report on global warming. The purpose of our analysis is to try and find out what the data is actually saying by stripping out some of the non-scientific rhetoric present in the report synopsis.

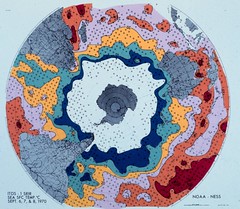

After presenting the ten indicators of global warming, the report discusses where the warming has been going. According to the NOAA, “More than 90 percent of the warming that’s happened on earth during the past 50 years has gone into the oceans.” Why is this important? First, it explains why sea levels are rising. Second, the oceans will hold the heat longer, extending the warming trend. The warming oceans set up the next section of the synopsis.

The next section begins to draw out implications of global warming, and here is where the science moves quickly into fear-mongering. Consider this passage:

At first glance, the amount of increase each decade – about a fifth of a degree Fahrenheit – may seem small. But the temperature increase of about 1 degree Fahrenheit experienced during the past 50 years has already altered the planet. Glaciers and sea ice are melting, heavy rainfall is intensifying and heat waves are becoming more common and more intense. Continued temperature increases will threaten many aspects of our society, including coastal cities and infrastructure, water supply and agriculture. People have spent thousands of years building society for one climate and now a new one is being created – one that’s warmer and more extreme.

No mention is made of the potential positive impact of a warming planet on agriculture, water supply, etc. The report just assumes that the climate from 1850 to 1960 is ideal for human civilization without justifying that highly dubious assumption. Maybe warming will actually be a net positive for human civilization, but nowhere does the report even raise this as a possibility (see this recent essay on how cities will adapt to climate changes). In addition, notice the use of these inflammatory words: “intensifying,” “intense,” “threaten,” “extreme.” Why use these words in a dispassionate scientific report unless you are driving an agenda? Just report the data, please.

The synopsis then anticipates those who will say that short-term temperatures may not be warmer in their location (for example, our local area was much colder than normal last winter). The report reminds readers that these local fluctuations are to be expected, but the overall trend is toward a warmer planet. Fair enough.

The most questionable section of the synopsis now takes the stage. The authors present six extreme weather events from 2009, chronicling deaths and property damage from floods, heat waves, cyclones, and record winds. Then, without comparing these 2009 weather events to weather events of previous years, the synopsis goes on to say, “Extreme weather events are unavoidable. But a warmer climate means that many of these events will be more frequent and more severe.” (emphasis added).

The message is clear: if we don’t stop global warming, our way of life is threatened and more of us will die. Really? Is there no chance that warming temperatures may produce any good consequences? Are all the consequences bad? Surely not, but we don’t hear about any of those possibilities in this report. It’s doom and gloom. Why? Because you can’t get taxpayer money without a crisis.

After analyzing the actual data in the report, there is a compelling case for global warming since 1960. The data does seem to point in that direction. The data also seems to indicate that the oceans are retaining the heat.

Beyond that, there is an attempt to scare people. We are given weather anecdotes from 2009 and told that “more bad stuff like this is going to happen.” That’s not good science and it is this kind of overblown rhetoric that makes people skeptical of global warming in the first place. If the authors have real data showing that extreme weather events have trended up over the last 50 years, they should have presented it.

One thing the synopsis made no attempt to do was connect global warming with human causation. The synopsis completely excludes the cause of the warming, choosing not to speculate (not sure if this is found in the detailed report).

Those are my thoughts. What do you think about this synopsis? What conclusions did you draw?