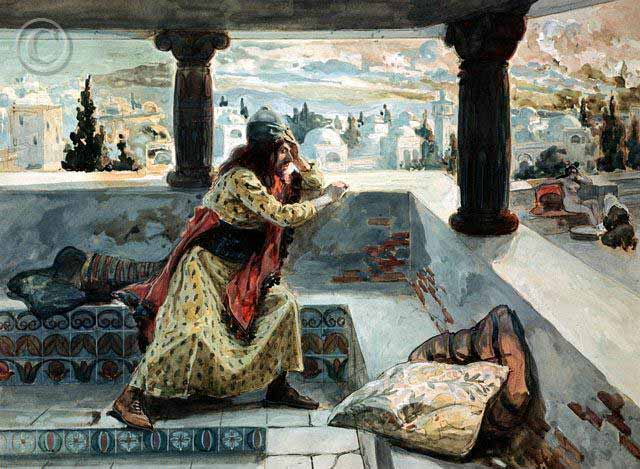

Psalm 51 is traditionally thought to be David’s lamentations for his sins against Bathsheba and Uriah. As the psalm begins, David asks for God’s forgiveness. Why God? Because even though David sinned against Bathsheba, Uriah, and others, it is God whom he has grieved the most. When we sin, we sin first and foremost against God.

Psalm 51 is traditionally thought to be David’s lamentations for his sins against Bathsheba and Uriah. As the psalm begins, David asks for God’s forgiveness. Why God? Because even though David sinned against Bathsheba, Uriah, and others, it is God whom he has grieved the most. When we sin, we sin first and foremost against God.

David acknowledges that God is a righteous judge and he also affirms that he has inherited a sinful nature. From his very conception he was sinful, thus affirming the doctrine of original sin, where the sinful nature of Adam and Eve has been passed down to all of their descendants.

David continues, in the psalm, to plead for God to purify him. This purification is not trivial, as Donald Williams and Lloyd Ogilvie, in Psalms 1–72, The Preacher’s Commentary Series explain.

The verb for ‘purge’ is intensive here, meaning ‘un-sin’ me, purify me from uncleanness. The word is commonly used in describing the cleansing of a leper’s house. Hyssop is also used to sprinkle blood in the rite of purification (Lev. 14:52). Similarly, hyssop was the agent used in spreading the blood of the Passover lamb on the lintels and doorposts of the Hebrew households in Egypt before the plague of death (Ex. 12:22). Underlying the purging of verse 7, then, is the concept of sacrificial blood. As we pray for purification, the leprosy of sin is removed.

David begs God to take away his guilt and to turn His face from David’s sins. David is concerned that God will take away His Spirit from David, just as He did with Saul. If only God will renew David in His eyes, David promises to evangelize and teach non-believers the ways of God.

David knows that his crimes merit the death penalty, according to the Law. If God will show him mercy, David will sing of His righteousness and publicly praise Him. David also knows that God wants a truly repentant and broken heart from David. David’s sacrifices mean nothing to God otherwise. Once David is restored, he asks that the nation of Israel also be restored so that she can once again give God the sacrifices He deserves. Allen Ross, in The Bible Knowledge Commentary (Old Testament:), summarizes Psalm 51:

The message of this psalm is that the vilest offender among God’s people can appeal to God for forgiveness, for moral restoration, and for the resumption of a joyful life of fellowship and service, if he comes with a broken spirit and bases his appeal on God’s compassion and grace.

Psalm 139 is a psalm of personal thanksgiving by David. In particular, David meditates on God’s omniscience and omnipresence. These two divine attributes lead David to understand God’s intimacy with His creation.

In verses 1-6, David affirms that God knows his every thought and his every action. In fact, God knows what David will say even before he says it. There is nothing about David that God does not know.

Is there anywhere David can go to avoid the all-seeing gaze of God? Is there any place he can travel to avoid intimacy with God? The answer given in verses 7-12 is “no.” Whether David is in heaven (the world above the surface of the earth) or hell (the world below the surface of the earth), God is there. Even if David flees to ends of the earth, God is there. Whether David is in darkness or light, God is with him. There is literally no place David can be where God is not holding David in His hand.

How does God know so much about David? Not only is He omniscient, but He created David in the womb. The embryonic David, in his mother’s womb, was skillfully woven together by God’s hand. He was involved with every detail of David’s growth in his mother’s womb. Going beyond the womb, every one of David’s days on earth were written ahead of time by God. There is nothing in David’s life that catches God by surprise.

In verses 17-18, David expresses wonder at God’s thoughts, and then abruptly, in verses 19-22, spells out his hatred for those opposing God. All those who speak against God, who take His name in vain, David hates with a “perfect hatred.” Donald Williams and Lloyd Ogilvie describe David’s hatred:

David’s strong reaction is not against ‘sinners.’ He is not a self-righteous judge who will not stain himself with this world. His reaction is against those who revile God’s name, who are His enemies (v. 20). It is those who hate God and rise up against Him that incur his wrath. And why is this so? Because the God who is so exquisitely described in verses 1–18 deserves our praise and worship. To withhold this is to deserve both human and divine wrath.

Finally, David invites God to test his own heart and mind to see if David is wicked in any way. He is willing to submit himself to God’s scrutiny. Williams and Ogilvie beautifully summarize the intimacy with each of us that God desires:

He formed us in the womb. He knows our frame. He sees our embryo. He fashions our days. He knows our thoughts. He hears our words. He knows when we sit down and when we stand up. He protects us. His hand is upon us. He who inhabits all things is near to us. We cannot escape His presence. In the light He sees us. In the dark He sees us. We are the continual object of His thoughts. He searches us. He changes us. Here is true intimacy, and if we can allow God to become intimate with us, we can establish a growing intimacy with each other. Secure in His presence and His love, we can risk opening up. We can even risk rejection, because we are held in His hand (v. 10).

The Book of Psalms is a collection of five sets of books that were combined into a single biblical book. The psalms are primarily praises and prayers for temple worship or personal devotion.

The Book of Psalms is a collection of five sets of books that were combined into a single biblical book. The psalms are primarily praises and prayers for temple worship or personal devotion. 1 and 2 Chronicles were originally a single work that was separated into two books when it was translated into the Greek Septuagint. The Chronicles was written to the Jewish people after they returned from Babylonian exile in the 6th century BC. Jewish tradition holds that Ezra was the author of Chronicles, but scholars are divided on the issue.

1 and 2 Chronicles were originally a single work that was separated into two books when it was translated into the Greek Septuagint. The Chronicles was written to the Jewish people after they returned from Babylonian exile in the 6th century BC. Jewish tradition holds that Ezra was the author of Chronicles, but scholars are divided on the issue. Skeptical scholars have long argued that David’s existence is doubtful because there was no archaeological evidence of his rule or his alleged dynasty. From roughly 850 BC onward, there have been many discoveries confirming the kings of Israel and Judah listed in the Bible, but pre-850 BC evidence has been almost nonexistent.

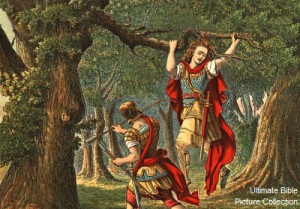

Skeptical scholars have long argued that David’s existence is doubtful because there was no archaeological evidence of his rule or his alleged dynasty. From roughly 850 BC onward, there have been many discoveries confirming the kings of Israel and Judah listed in the Bible, but pre-850 BC evidence has been almost nonexistent. Chapter 13 begins with an ominous declaration: Amnon loves Tamar. Amnon is David’s firstborn son and heir to David’s throne. His mother is Ahinoam. Tamar is the daughter of David and Maacah. Maacah and David also have a son named Absalom, so Absalom and Tamar are brother and sister. Tamar is Amnon’s half-sister.

Chapter 13 begins with an ominous declaration: Amnon loves Tamar. Amnon is David’s firstborn son and heir to David’s throne. His mother is Ahinoam. Tamar is the daughter of David and Maacah. Maacah and David also have a son named Absalom, so Absalom and Tamar are brother and sister. Tamar is Amnon’s half-sister. In previous chapters, Israel has been at war with the Ammonites, but they have not yet completely defeated them. As chapter 11 begins, David sends the army to finish off the Ammonites once and for all. They have retreated to a city named Rabbah, so David’s forces are besieging Rabbah.

In previous chapters, Israel has been at war with the Ammonites, but they have not yet completely defeated them. As chapter 11 begins, David sends the army to finish off the Ammonites once and for all. They have retreated to a city named Rabbah, so David’s forces are besieging Rabbah. Some time after David has placed the ark in Jerusalem, a palace has been built for him, and he has a period of rest from his enemies, he decides that he should build a temple to house the ark (God’s home on earth). David communicates his plans to Nathan, the prophet, and Nathan affirms his plans. However, that night Nathan hears from God about His plans for David, and they are not at all what Nathan expects!

Some time after David has placed the ark in Jerusalem, a palace has been built for him, and he has a period of rest from his enemies, he decides that he should build a temple to house the ark (God’s home on earth). David communicates his plans to Nathan, the prophet, and Nathan affirms his plans. However, that night Nathan hears from God about His plans for David, and they are not at all what Nathan expects! Following the death of Saul in 1 Sam 31 (around 1010 BC), David is anointed king over the tribe of Judah. The other tribes, however, give their fealty to Saul’s remaining son, Ish-Bosheth. This is the situation for 7 years, until Ish-Bosheth is killed by two assassins. It is important to note that David has nothing to do with the assassination and he, in fact, has the assassins executed for their deed.

Following the death of Saul in 1 Sam 31 (around 1010 BC), David is anointed king over the tribe of Judah. The other tribes, however, give their fealty to Saul’s remaining son, Ish-Bosheth. This is the situation for 7 years, until Ish-Bosheth is killed by two assassins. It is important to note that David has nothing to do with the assassination and he, in fact, has the assassins executed for their deed. During the time covered in 1 Samuel 18-29, David built up a small army of 600 men from the outcasts of Israel, while Saul continued to hunt David down in order to kill him. When we finally get to chapters 30-31, David and Saul are both facing armed conflicts, but with separate enemies. The narrator places these conflicts one after another to contrast how different Saul and David, with respect to their relationships with God, truly are.

During the time covered in 1 Samuel 18-29, David built up a small army of 600 men from the outcasts of Israel, while Saul continued to hunt David down in order to kill him. When we finally get to chapters 30-31, David and Saul are both facing armed conflicts, but with separate enemies. The narrator places these conflicts one after another to contrast how different Saul and David, with respect to their relationships with God, truly are. Between chapters 8 and 15 in 1 Samuel, Israel has received the king she requested in the person of Saul. From the beginning, we know that Saul was not a man “after God’s heart” and although Saul has some military successes against Israel’s enemies, especially the Philistines, his disobedience of God’s commands would eventually cause him to lose his kingship.

Between chapters 8 and 15 in 1 Samuel, Israel has received the king she requested in the person of Saul. From the beginning, we know that Saul was not a man “after God’s heart” and although Saul has some military successes against Israel’s enemies, especially the Philistines, his disobedience of God’s commands would eventually cause him to lose his kingship.