In chapter 8 of Acts, Stephen’s death sparks an intense persecution against the church in Jerusalem. Many of the believers must flee the city, but the apostles decide to stay. It seems likely that the persecution was targeted more toward the Greek-speaking Christians, as they were more closely associated with Stephen. However, the persecution may have spread to the Hebrew Christians as well. Saul tracks down Christians and has them arrested and thrown in prison. Some brave Christians give Stephen a proper burial, even though it was prohibited by Jewish law.

The attacks on the Christians in Jerusalem have an unintended consequence, however. As they flee the city and travel to other towns and villages, the believers start to spread the story of Jesus to the surrounding region, something they hadn’t done for the first several years after Pentecost.

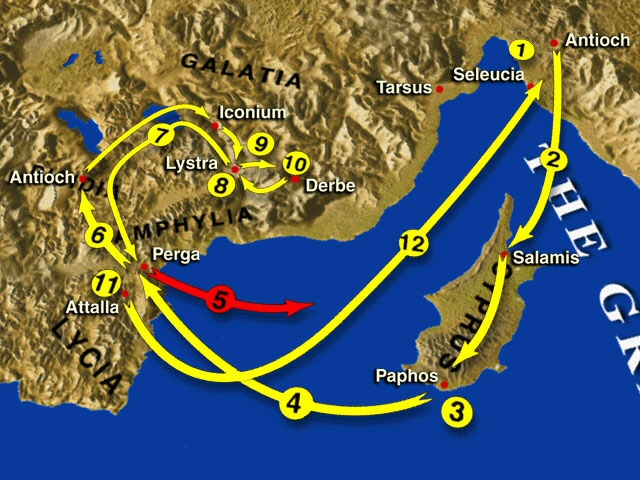

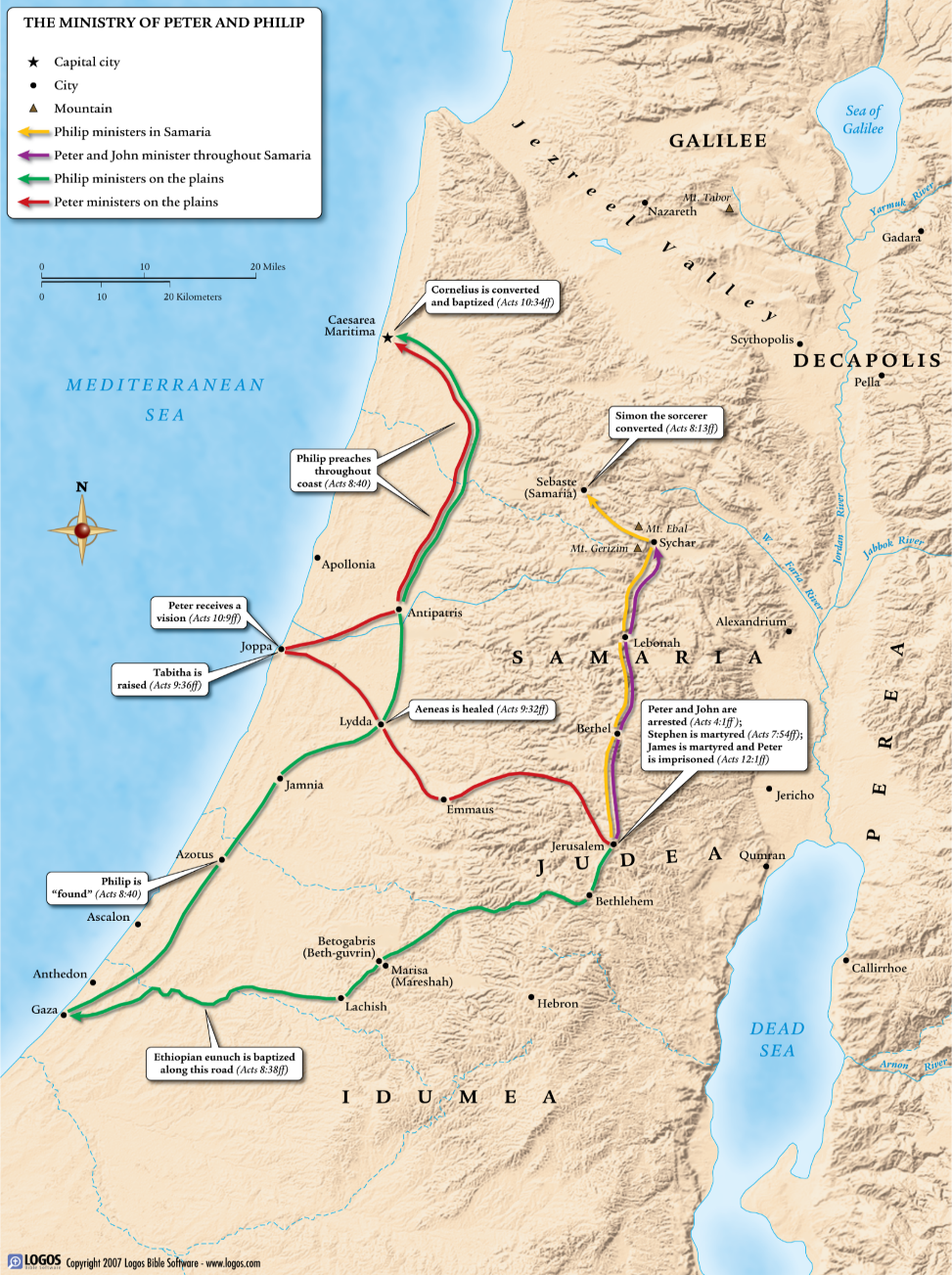

Luke focuses on Philip. Recall that he was one of the seven chosen to ensure the Hellenist widows were cared for. As a Hellenist Christian, he was probably one of the first to leave Jerusalem. He travels to a city in Samaria and preaches “the Christ.” It is unclear which city Philip visits first, although Darrell Bock suggests Sychar (see map below). Sychar is the religious center of Samaria, so it would make sense that Philip would go there first.

Philip performs miraculous exorcisms and healings, all of which cause the Samaritans to listen to what he has to say about Jesus. Luke reports that a significant number receive the message and that there is great joy in the city.

In verses 14-17, Luke reports that Peter and John travel from Jerusalem to see for themselves what is happening in Samaria. When Peter and John arrive, they pray for the Samaritan converts and lay hands on them. Immediately, the Holy Spirit manifests himself in the new believers. We are not sure what occurs, but we can speculate that they were able to speak in foreign languages just as the disciples were able to do at Pentecost. In fact, some scholars refer to this event as the Samaritan Pentecost.

A question arises, however, as to why the Samaritan believers did not immediately receive the Holy Spirit when they professed and were baptized in Jesus’ name. Only after Peter and John lay hands on them does this occur.

As mentioned in a previous lesson, there is not a set pattern in the Book of Acts for baptism and receipt of the Holy Spirit, so we must not take this particular story and try to make it normative for the church. It seems that the addition of the Samaritans to the early church required apostolic confirmation to keep the church from dividing. We need to remember that the Jews and Samaritans actively dislike each other. Clinton Arnold, in [amazon_textlink asin=’B004MPROQC’ text=’John, Acts: Volume Two (Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary)‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’8feb6d36-63e9-11e7-af42-e5c2f3ec5011′], recounts the history of the Samaritans:

The Samaritans viewed themselves as Israelites, true remnants of the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh, who maintained a monotheistic faith and upheld the Torah as holy scripture. They kept the rite of circumcision, regularly observed the Sabbath and the Jewish festivals, and honored Moses as the greatest of the prophets. The Jews, however, viewed the Samaritans as ‘half breeds’—descendants of Mesopotamian (Gentile) colonists who settled in the area and intermarried with the Jews remaining there after the Jewish exile by Assyria (2 Kings 17:24-31).

At the heart of the schism between Jews and Samaritans in the first century was the fact that Samaritans rejected the Jewish temple worship. Three centuries earlier, they had constructed their own temple on Mount Gerizim. They also rejected all of the Hebrew Bible except the first five books of Moses. The hostility intensified in the century before Christ when John Hyrcanus destroyed their temple (107 B.C.) and devastated many of their cities. Under the Syrian ruler Antiochus Epiphanes (167 B.C.), they had requested that their temple be dedicated to Zeus Hellenios, thus identifying Zeus with Yahweh.

The Jewish rabbi Ben Sira refers to the Samaritans as ‘the foolish people that live in Shechem.’ Jews regarded Samaritans on the same level as Gentiles in ritual and purity matters. Not only did Jews prohibit intermarriage with Samaritans, but they did not even allow a Samaritan to convert to Judaism. The apostle John summarizes the situation well when he says, ‘Jews do not associate with Samaritans’ (John 4:9).

If the apostles did not personally visit the new Samaritan converts and confirm that they were truly added to the church by the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, there would likely have been a schism. The bad blood between the Samaritans and Jews would have caused considerable damage to the movement. But with the Holy Spirit coming to the Samaritans, all doubts are erased, and church unity is preserved.

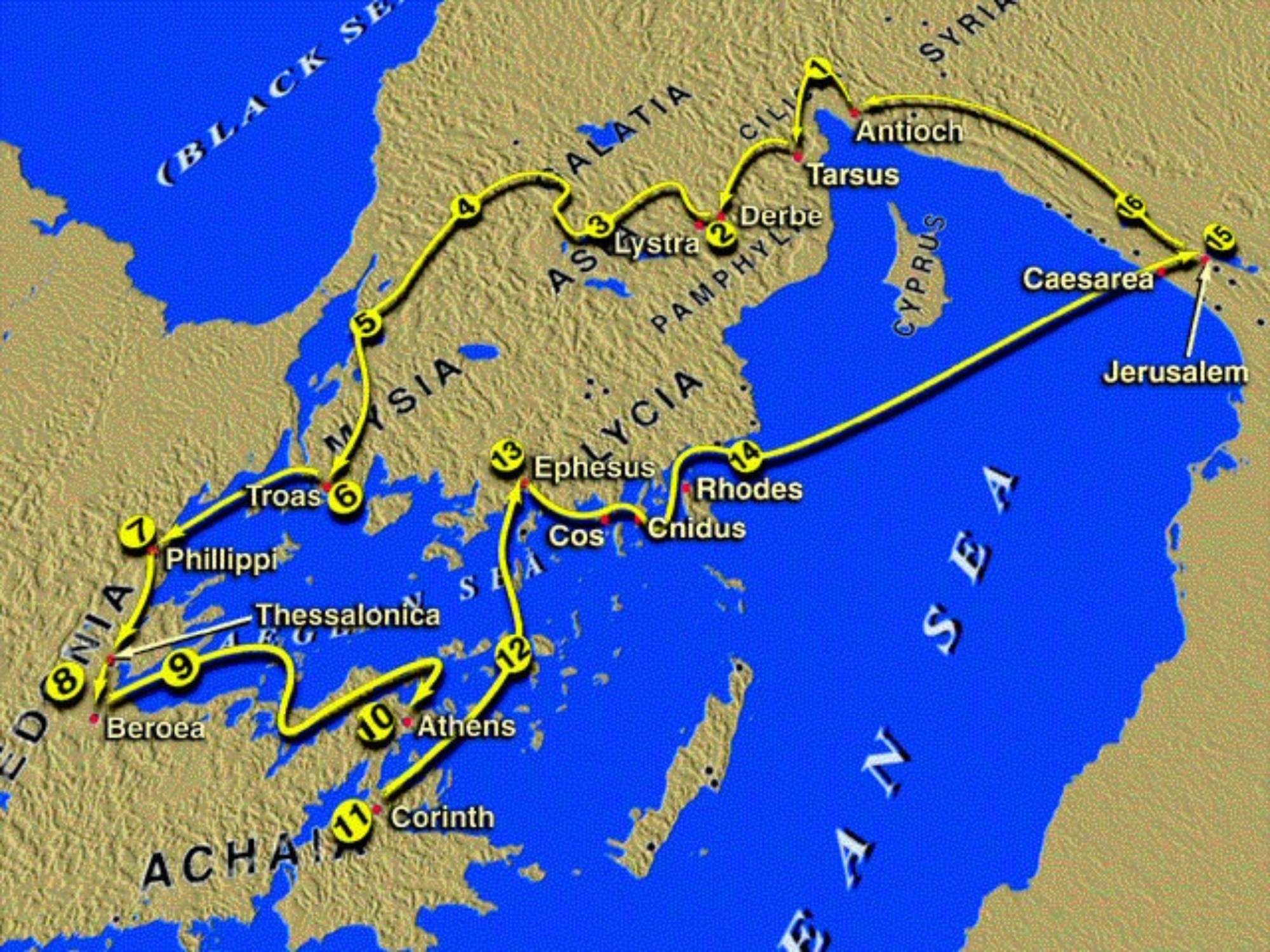

In verse 26, an angel instructs Philip to leave Samaria and go down south of Jerusalem onto the road that leads past Gaza (see map above). As Philip is walking on the road, an Ethiopian official is riding in a chariot and reading aloud from an Isaiah scroll. Clinton Arnold explains that in the

Greco-Roman period, ‘Ethiopia’ referred to the land south of Egypt—what is today the Sudan and modern Ethiopia. In Old Testament times, this was the land of Cush (see Est. 1:1; 8:9; Isa. 11:11). The term ‘Ethiopia’ has come to mean the land of the ‘Burnt-Faced People,’ indicating their black skin. The man whom Philip encounters is most likely from the kingdom of Nubia located on the Nile River between Aswan and the Fourth Cataract (a waterfall-like area of rapids). The capital of this region is Meroe.

Since the Ethiopian had come to Jerusalem to worship, he would have been called a God-fearer. God-fearers are people who worship the God of Israel, but who are not official converts to Judaism (proselytes). In this case, because the Ethiopian is a eunuch, Jewish law forbids him from becoming a proselyte. Arnold surmises, “As a Gentile God-fearer, he could not have taken part in the temple services in Jerusalem. At the most, he could be admitted into the Court of the Gentiles. Perhaps the Ethiopian came for one or more of the three great pilgrim festivals (Passover, Pentecost, or Tabernacles).”

The Holy Spirit directs Philip to engage with the eunuch, so Philip asks him if he understands what he is reading. The eunuch tells him no and invites Philip into his chariot to explain the words (Isaiah 53:7-8) to him. Philip explains that the sheep led to slaughter is none other than the Messiah, Jesus of Nazareth. From there, Philip expands upon how the Scriptures all point toward Jesus as the promised Messiah.

As the chariot passes by water, the eunuch asks Philip to baptize him because the eunuch has understood and believed what Philip has said about Jesus. Philip baptizes the eunuch and then disappears, taken by the Holy Spirit to a city just north called Azotus. Philip continues his missionary work up the coast of Judea and Samaria until he reaches Caesarea, where he resides for at least 20 years (see Acts 21).

Why would Luke spend so much time on the conversion of a single man? First, the Greco-Roman world regarded Ethiopia, which was south of Egypt, as the “end of the earth.” Luke wanted to show that the command to take the gospel to the ends of the earth in Acts 1:8 is being accomplished. Second, Luke is recording the first conversion of a black man, a man who belongs to a non-Semitic ethnic group. All ethnic groups are to be included in the kingdom of God. Third, the eunuch is the first example of a God-fearer coming to believe in Jesus. God-fearers were excluded from becoming full Jews, but in Jesus’ church, they were not excluded. They are full members, along with all other converts.