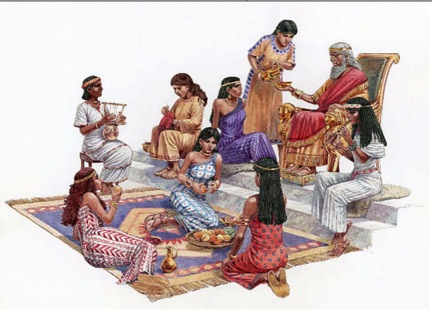

Under Solomon, Israel reached its historical pinnacle with regards to geography, peace with her neighbors, and material wealth for the king and his administration. Solomon also established a large military, trade with nearby nations, and an impressive bureaucracy to administer the kingdom of Israel.

Under Solomon, Israel reached its historical pinnacle with regards to geography, peace with her neighbors, and material wealth for the king and his administration. Solomon also established a large military, trade with nearby nations, and an impressive bureaucracy to administer the kingdom of Israel.

For many years, Solomon more or less obeyed the Torah, as his father David did. But as time passed, Solomon accumulated hundreds of wives who would become his downfall. This is where chapter 11 of 1 Kings picks up the narrative.

In verses 1-3, we learn that Solomon has married hundreds of foreign women, most of them for the purpose of making treaties with other nations. It was common practice for kings of this era to marry princesses from other nations to stabilize political relations. However, Solomon was not the king of a typical nation. Paul R. House, in 1, 2 Kings: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture (The New American Commentary), describes Solomon’s errors:

First, he has disobeyed Moses’ law for marriage, which constitutes a breach of the agreement Solomon makes with God in 1 Kgs 3:1–14; 6:11–13; and 9:1–9. Moses says in Deut 7:3–4 and Exod 34:15–16 that Israelites must not intermarry with noncovenant nations. Why? Because God says ‘they will turn your sons away from following me to serve other gods’ (Deut 7:4). Judgment will then result. Second, Solomon has broken Moses’ commands for kings (cf. Deut 17:14–20). Moses explicitly says, ‘He must not take many wives or his heart will be led astray’ (Deut 17:17).

In verses 4-8, the author of Kings reports that Moses’s dire predictions all come true with Solomon. Solomon not only tolerates his wives’ gods, he builds worship centers for them. Thus the Lord punishes Solomon in verses 9-13.

Because of Solomon’s sins against God, Solomon’s son would lose part of the kingdom. God tells Solomon,

I will most certainly tear the kingdom away from you and give it to one of your subordinates. Nevertheless, for the sake of David your father, I will not do it during your lifetime. I will tear it out of the hand of your son. Yet I will not tear the whole kingdom from him, but will give him one tribe for the sake of David my servant and for the sake of Jerusalem, which I have chosen.

Solomon’s son, Rehoboam, would rule over the tribes of Judah and Benjamin, but another king would rule over the other 10 tribes of Israel. Who would this other ruler be? The answer lies in verses 26-40.

One of Solomon’s own administrators, Jeroboam, is met on the road out of Jerusalem by the prophet Ahijah. Ahijah tells Jeroboam that God is going to make him king over the 10 tribes of Israel, excluding Judah and Benjamin. The reason he is taking this part of the kingdom away from Solomon’s son (and David’s grandson), Rehoboam, is because Solomon has worshipped other gods and has not followed the Law (or Torah) as his father David did. God promises Jeroboam that if he obeys the Torah, as David did, God will bless him with a dynasty. Solomon learns of this promise to Jeroboam and he tries to kill him, but Jeroboam escapes to Egypt until Solomon dies.

Chapter 11 ends with the death of King Solomon. He ruled 40 years and his son, Rehoboam, succeeded him. What can we learn from chapter 11 about God? Paul R. House writes,

Theologically, the passage reemphasizes God’s faithfulness. This time the author depicts the Lord as the God who keeps promises even when the person who is the object of the promise fails to be righteous. For David’s sake, and for the sake of Solomon, the Lord refuses to obliterate the nation. Despite this mercy, however, Israel must still face the consequences of idolatry. God does judge.

House also emphasizes what the chapter says about leaders who sin:

Further, the text stresses how a leader’s sin can impact others. Although it is doubtful that Solomon can be held responsible for introducing idolatry into Israel (cf. the Book of Judges), his religious open-door policy serves to legitimize the practice in a way that no commoner’s similar actions could. Just as one holy person, such as Abraham or Moses, can bless a whole people, so one significant idolater can create spiritual cancer in a people. Had Solomon continued to seek God’s favor rather than wealth and power, he could have helped Israel continue to enjoy prosperity. Instead, he illustrates the principle that sin always affects others.

A final point to be made is that God still expects obedience even in a multicultural, pluralistic society. Solomon could not use the excuse that he needed to bend the rules of the Torah to survive in the ancient near east. Likewise, we can’t expect God to bend the rules for us today when His principles become unpopular. He simply will not do that.

In the nation of Israel, since the division of the kingdom, there have been 7 kings and 4 different dynasties (successions of rulers who are of the same family). The year is 874 BC and the eighth king of Israel comes to the throne. His name is Ahab and his reign begins at about the time King Asa of Judah’s reign is ending.

In the nation of Israel, since the division of the kingdom, there have been 7 kings and 4 different dynasties (successions of rulers who are of the same family). The year is 874 BC and the eighth king of Israel comes to the throne. His name is Ahab and his reign begins at about the time King Asa of Judah’s reign is ending. Solomon has died, so now his son Rehoboam is going to take over as king of all Israel in 931 BC. Rehoboam travels to a place called Shechem to meet with the leaders of the 10 northern tribes, where he presumes that he will be coronated king (Judah and Benjamin are the other 2 tribes in the south).

Solomon has died, so now his son Rehoboam is going to take over as king of all Israel in 931 BC. Rehoboam travels to a place called Shechem to meet with the leaders of the 10 northern tribes, where he presumes that he will be coronated king (Judah and Benjamin are the other 2 tribes in the south). The books of 1 and 2 Kings were originally a single work, but were separated into two parts when they were translated into the Greek New Testament (the Septuagint). The Septuagint also combined Samuel and Kings into a four-part history of the monarchy of Israel (First, Second, Third, Fourth Book of Kingdoms).

The books of 1 and 2 Kings were originally a single work, but were separated into two parts when they were translated into the Greek New Testament (the Septuagint). The Septuagint also combined Samuel and Kings into a four-part history of the monarchy of Israel (First, Second, Third, Fourth Book of Kingdoms).