As chapter 32 begins, Moses has been up on Mount Sinai for weeks (40 days) receiving instructions from God. This is the longest period of time, so far, that Moses has been away from the camp of Israel at the base of Mount Sinai. The outcome of Moses’ communion with God will be the two tablets of the Testimony, which are engraved by God himself.

As chapter 32 begins, Moses has been up on Mount Sinai for weeks (40 days) receiving instructions from God. This is the longest period of time, so far, that Moses has been away from the camp of Israel at the base of Mount Sinai. The outcome of Moses’ communion with God will be the two tablets of the Testimony, which are engraved by God himself.

The people of Israel, however, are anxious because Moses has been absent so long. In verse 1 of Exodus 32, some of the Israelites go to Aaron (who has been left in charge while Moses is gone) and ask him to make an idol that will represent Yahweh, the God who brought them out of Egypt.

There is some confusion here because of translation of a Hebrew word for “god(s).” The NIV translates verse 1 to say “Come, make us gods who will go before us,” while other translations render the Hebrew word in the singular: “Come, make us a god who will go before us.” It seems that the better translation is the singular, which means that the sin of the Israelites is not polytheism (worshipping more than one god), but idolatry (worshiping an image of God).

So, the Israelites are not looking to replace Yahweh with other gods, they are wanting to worship images of him. Remember that they had already agreed to the Ten Commandments, which includes the command to not commit idolatry, back in chapter 24. At that time, before Moses went back up the mountain to receive further instructions from God, the people had made a covenant with God, based on the Ten Commandments. Here we are just a month or so later, and they have already broken one of the most important commandments!

Aaron, instead of refusing the request of the people, makes an idol, in the shape of a calf, out of the gold earrings that they had received from the Egyptians. In addition, Aaron builds an altar in front of the golden calf and then announces a festival will be held to make offerings to the calf.

Why make an idol in the form of a calf? In both Egypt and Canaan, there were many gods that were worshiped in the form of a bull. According to The Chronological Study Bible: New King James Version,

Cattle were common images for deities in the ancient Near East. In Egypt, Hathor , a very popular goddess, was represented as a cow, as a woman with cow horns or ears or both, and as a human with a cow’s head. The usual manner of depicting a male deity in Syria-Palestine was to represent him either as a bull or with some features of a bull usually horns. In Babylon the bull images of Hadad lined the main processional street.

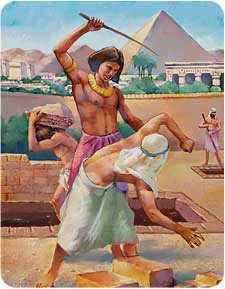

The Israelites were reverting back to the pagan religious practices they learned from the Egyptians and surrounding nations.

In verses 7-8, God tells Moses to go back down the mountain because God sees the grave sins of the people. In verses 9-10, God threatens to destroy Israel since they have already broken his covenant, offering to start over with Moses as the father of a new covenant people.

Over the next four verses, Moses intercedes for the Israelites and begs God to relent. He reminds God about the promises God made to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Israel), that he would make their descendants “as numerous as the stars in the sky and . . . give [their] descendants all this land [he] promised them, and it will be their inheritance forever.” God does indeed relent and does not destroy the people of Israel.

Verses 15-18 describe Moses’ journey back down to the base of the mountain with the two stone tablets of the Testimony. At some point along the way, he meets up with Joshua, who was probably waiting half way down the mountain for Moses. They hear the shouting of the Israelites at the bottom of the mountain. Joshua thinks they are at war, but Moses knows better.

Moses throws the tablets to the ground, breaking them. This symbolizes that the covenant is broken, the covenant that the people made With God just weeks before. Douglas Stuart, in Exodus: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture (The New American Commentary), explains that the

tablets were not divided among the commandments, but each tablet contained all ten, so that one tablet represented the suzerain’s copy and one the vassal’s, in accordance with standard ancient Near Eastern document preservation practices. These two tablets were the most valuable material thing on earth at that time, as the reader is now informed clearly, so that later when Moses breaks them, the reader can appreciate the severity of the sin that would have caused him to do something so destructive to something so precious.

Moses then destroys the calf and confronts Aaron, asking “What did these people do to you, that you led them into such great sin?” Aaron’s response, in verses 22-24, is to blame the Israelites and not take responsibility for his part in the golden calf episode.

At this point, seeing the chaos of pagan worship running rampant among the Israelites, Moses asks all those who are for the Lord to come to him. Evidently, the tribe that rallied to Moses was made up primarily of Levites (which is the tribe of Moses and Aaron). Moses, in order to stamp out the idolatry, and in order to execute divine judgment on the nation of Israel, instructs the Levites to kill those Israelites committed to idol worship, men who are their brothers, friends, and neighbors.

In verse 30, Moses reminds the people of their great sin and he offers to go to the Lord and make atonement. When Moses speaks to God, he offers to have his name removed from the book (Book of Life) God has written, along with the rest of the Israelites, even though Moses did not sin.

Instead, God refuses to remove Moses from the Book of Life, but promises to remove those names of the people who did sin against God. God also promises to strike Israel with a plague as punishment for their sin, and so he does.

What more can be said about the Book of Life? Douglas Stuart provides a helpful overview:

First, the Book of Life is a record of those going on to eternal life as opposed to those who by their own decisions have rejected God and his salvation (cf. John 3:19–20). To have one’s name in the Book of Life is to have persevered in faith and obedience to God until the final judgment of the earth. To have one’s name blotted out is to have offended God by lack of faith and, accordingly, by disobedience so that one cannot continue to live, that is, have eternal life.

Moreover, important for understanding God’s purposes in judgment is to appreciate that everyone starts out in the Book of Life. It is a book of the living, and all who are born originally appear in it. God does not arbitrarily put some names in it and not others. All who come into the world have the potential for eternal life, according to God’s will (1 Tim 2:3–4; 2 Pet 3:9) but most ignore, reject, disdain, put off, or otherwise forfeit that potential—and so their names are eventually blotted out of the Book of Life. When they appear at the judgment and the books are opened (Dan 7:10; Rev 20:12), their names will not appear in the Lamb’s Book of Life because they chose a different direction during their lives on earth from the direction God prescribed. Their rejection of him eventually earns them rejection from being listed among the living. Their fate is then destruction, the second death (Rev 2:11; 20:6, 14; 21:18).

In chapters 7-12, the power of God would be demonstrated to Pharaoh and all the people of Egypt. Recall that Pharaoh told Moses and Aaron that he did not know their God, and God promised that he soon would. Ten plagues would be visited upon the Egyptians, with each successive plague bringing yet more devastation on top of the previous.

In chapters 7-12, the power of God would be demonstrated to Pharaoh and all the people of Egypt. Recall that Pharaoh told Moses and Aaron that he did not know their God, and God promised that he soon would. Ten plagues would be visited upon the Egyptians, with each successive plague bringing yet more devastation on top of the previous.

At the beginning of chapter 19, the Israelites have finally reached the base of Mount Sinai, on the third day of the third month after the Exodus from Egypt (48 days). The people of Israel would reside at Mount Sinai for a full year – the rest of the Book of Exodus, all of the Book of Leviticus, and the first ten chapters of the Book of Numbers all take place here.

At the beginning of chapter 19, the Israelites have finally reached the base of Mount Sinai, on the third day of the third month after the Exodus from Egypt (48 days). The people of Israel would reside at Mount Sinai for a full year – the rest of the Book of Exodus, all of the Book of Leviticus, and the first ten chapters of the Book of Numbers all take place here. Following the crossing of the Red Sea, the Israelites continued to travel south in the desert of the Arabian peninsula. As they moved further away from Egypt, they simultaneously moved further away from civilization. They became more and more hungry because there were few plants and animals for them to eat. This is the situation when Exodus 16 picks up.

Following the crossing of the Red Sea, the Israelites continued to travel south in the desert of the Arabian peninsula. As they moved further away from Egypt, they simultaneously moved further away from civilization. They became more and more hungry because there were few plants and animals for them to eat. This is the situation when Exodus 16 picks up. In chapters 12 and 13, the Israelites escaped from Egypt due to the mighty hand of God, and have traveled some distance to the southeast, but not out of Egyptian territory. Chapter 14 begins the account of one of the most famous miracles performed by God for the Israelites, the parting of the Red (or Reed) Sea.

In chapters 12 and 13, the Israelites escaped from Egypt due to the mighty hand of God, and have traveled some distance to the southeast, but not out of Egyptian territory. Chapter 14 begins the account of one of the most famous miracles performed by God for the Israelites, the parting of the Red (or Reed) Sea. In chapter 12 of the Book of Exodus, we come to the final plague that God will visit upon Egypt. Unlike the other plagues, this one requires preparation by the Israelites, and that preparation will be memorialized by the Israelites forever. Chapter 12 combines the instructions to the Israelites on how to memorialize the events surrounding their salvation from the final plague and God’s rescuing them from Egypt, along with the narrative explaining what actually occurred.

In chapter 12 of the Book of Exodus, we come to the final plague that God will visit upon Egypt. Unlike the other plagues, this one requires preparation by the Israelites, and that preparation will be memorialized by the Israelites forever. Chapter 12 combines the instructions to the Israelites on how to memorialize the events surrounding their salvation from the final plague and God’s rescuing them from Egypt, along with the narrative explaining what actually occurred. After successfully convincing their fellow Israelites that the God of their ancestors had sent them, Moses and Aaron boldly approach Pharaoh and request that he let them go to the desert to worship. Pharaoh’s response frames the events that will take place in chapters 7 through 12 of Exodus.

After successfully convincing their fellow Israelites that the God of their ancestors had sent them, Moses and Aaron boldly approach Pharaoh and request that he let them go to the desert to worship. Pharaoh’s response frames the events that will take place in chapters 7 through 12 of Exodus. Chapter 4 of Exodus can be split into 3 sections: Miraculous Signs for Moses, Moses’ Return to Egypt, and the Reunion of Moses and Aaron.

Chapter 4 of Exodus can be split into 3 sections: Miraculous Signs for Moses, Moses’ Return to Egypt, and the Reunion of Moses and Aaron. Chapter 3 of Exodus recounts one of the most famous passages in all of Scripture, the story of Moses and the Burning Bush. Moses is tending his father-in-law’s flocks near a mountain called Horeb. Some scholars believe that this mountain is identical with Mount Sinai, where Moses would later receive the Ten Commandments.

Chapter 3 of Exodus recounts one of the most famous passages in all of Scripture, the story of Moses and the Burning Bush. Moses is tending his father-in-law’s flocks near a mountain called Horeb. Some scholars believe that this mountain is identical with Mount Sinai, where Moses would later receive the Ten Commandments.