Post Author: Bill Pratt

Biblical scholar Douglas Stuart, in his Exodus: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture (New American Commentary), identifies 8 possible ways to translate the word ‘eleph from Hebrew to English. Each of these translations could be used in Exodus 12:37, with context being the determinant. The 8 possible translations are: 1) cattle, 2) clans, 3) divisions, 4) families, 5) oxen, 6) tribes, 7) military platoon or squad, and 8) thousand.

As you can see, this word ‘eleph has a tremendous semantic range. The NIV translators have decided to translate the word as “thousand” but Stuart believes this is a mistake. Since the word ‘eleph is being used in the context of counting foot soldiers, then Stuart argues that option 7 is the most appropriate translation. Given this translation of platoon or squad, what number of soldiers would that indicate?

Mendenhall suggests that it was the number of men of fighting age (above age twenty; cf. Num 1:3) that a single tribal subset (extended family) or village or district of a larger town could produce. What we do not know is the actual numbers of these extended families or village districts. In the case of a larger family or district, the number might be as many as twenty. A small village or district might produce just a handful. For general purposes of calculation, it may be assumed that most ʾelephs were not larger than fifteen and perhaps averaged a dozen. . . .

Accordingly, six hundred ʾelephs, the number mentioned in Exod 12:37, probably would contain not more than 7,200 fighting men, at an average of a dozen fighting men per ʾeleph. If one assumes that many of these were single, but that most may have been married, that most who were married had children, and that there were many men who could not fight because they were either too old or too young or infirm, the total number of Israelites who left Egypt might in fact have been around 28,800–36,000 (assuming three or four nonfighters for every fighter). This is a large and formidable number but by no means the two million or so that a misleading calculation based on taking ʾeleph unjustifiably as “thousand” would yield.

Stuart concludes with the following:

Twenty or thirty thousand people is a number that easily can fit into many modern sorts of venues, from small sports stadiums to beaches to public gatherings and rallies, a fact that may help modern readers of the book visualize the entire Israelite contingent, who were often in one place at one time. It is a number that fits the facts of the book of Exodus well. Such a number of Israelites is large enough to require the miraculous provisions of food and water that the book describes; it is small enough for the whole nation to gather encamped around the tabernacle at the various places listed on the Israelite wilderness itinerary. For most occasions of listening to speeches, the men only would have gathered, several thousand or so in number, not too many to hear a speech shouted at them, especially if its words were relayed. Yet several thousand troops were formidable as a fighting force when directed at one place at a time.

We may never know the exact number of Israelites who traveled from Egypt, but Stuart’s analysis seems plausible to me. Because the word ‘eleph can be translated in so many different ways, we can’t be sure that it should be translated as “thousand” in Exodus 12:37.

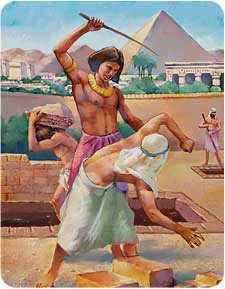

After successfully convincing their fellow Israelites that the God of their ancestors had sent them, Moses and Aaron boldly approach Pharaoh and request that he let them go to the desert to worship. Pharaoh’s response frames the events that will take place in chapters 7 through 12 of Exodus.

After successfully convincing their fellow Israelites that the God of their ancestors had sent them, Moses and Aaron boldly approach Pharaoh and request that he let them go to the desert to worship. Pharaoh’s response frames the events that will take place in chapters 7 through 12 of Exodus. Chapter 3 of Exodus recounts one of the most famous passages in all of Scripture, the story of Moses and the Burning Bush. Moses is tending his father-in-law’s flocks near a mountain called Horeb. Some scholars believe that this mountain is identical with Mount Sinai, where Moses would later receive the Ten Commandments.

Chapter 3 of Exodus recounts one of the most famous passages in all of Scripture, the story of Moses and the Burning Bush. Moses is tending his father-in-law’s flocks near a mountain called Horeb. Some scholars believe that this mountain is identical with Mount Sinai, where Moses would later receive the Ten Commandments. The astute Bible reader will notice that Moses is the fourth important character in the Pentateuch to find his wife through an incident at a well. The other three are Isaac, Jacob, and Judah. Does this repetition indicate that these stories are being fabricated? Is it possible that wells were involved in all of these marriages?

The astute Bible reader will notice that Moses is the fourth important character in the Pentateuch to find his wife through an incident at a well. The other three are Isaac, Jacob, and Judah. Does this repetition indicate that these stories are being fabricated? Is it possible that wells were involved in all of these marriages? After Pharaoh’s previous failures, he tries yet another approach to break the will of the Hebrews. In verse 22 of chapter 1, he decrees that every male child of the Hebrews must be thrown into the Nile River.

After Pharaoh’s previous failures, he tries yet another approach to break the will of the Hebrews. In verse 22 of chapter 1, he decrees that every male child of the Hebrews must be thrown into the Nile River. Shiphrah and Puah did indeed lie to Pharaoh about the Hebrew women giving birth quicker than the Egyptian women. Doesn’t the Bible expressly condemn lying? Yes, it does in several places. So what are we to make of these verses in Exodus 1? How is it that God rewarded the midwives for lying to Pharaoh?

Shiphrah and Puah did indeed lie to Pharaoh about the Hebrew women giving birth quicker than the Egyptian women. Doesn’t the Bible expressly condemn lying? Yes, it does in several places. So what are we to make of these verses in Exodus 1? How is it that God rewarded the midwives for lying to Pharaoh?