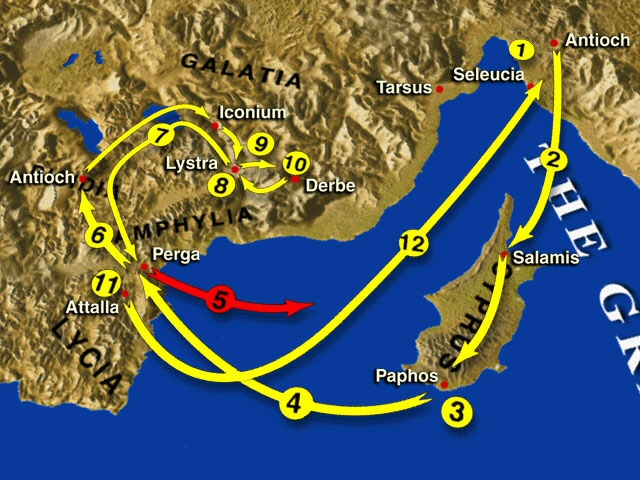

In about AD 45, Paul and Barnabas set out from Syrian Antioch to evangelize Gentiles in Asia Minor. Chapter 14 starts with their entrance into the city of Iconium (see map below). Iconium is a major Roman city inhabited mostly by Gentiles with a small number of Jews. Clinton Arnold, in [amazon_textlink asin=’B004MPROQC’ text=’John, Acts: Volume Two (Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary)‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’6508ca2a-7d06-11e7-b98a-130760e7f1f7′], writes that there “is evidence that the population worshiped the Asia Minor mother goddess Cybele, Herakles (Hercules), Zeus Megistos (Jupiter Optimus Maximus), as well as Apollo.”

Paul and Barnabas convince a number of Jews and Gentiles to believe in the gospel message, but the city is divided. Even though God grants Paul and Barnabas the power to perform miracles, animosity toward them grows among the unbelieving Jews of the city. Eventually, they persuade some of the Gentiles to join them in stoning the missionaries to death. Paul and Barnabas, however, discover the plot and leave the city for Lystra and Derbe (see map below).

When the missionaries arrive at Lystra, a man crippled from birth listens intently to Paul. Paul sees his faith and commands him to stand up. The man is miraculously healed and the people of Lystra, seeing this miracle, decide that Paul and Barnabas are the gods Hermes and Zeus in human form. Why would the Lystrans react this way?

Clinton Arnold offers the following plausible explanation:

The famous first-century Roman poet Ovid tells a story about Zeus and Hermes taking mortal form and visiting an elderly couple in their humble Phrygian countryside home [the area in which Lystra is located]. Leading up to this, Zeus and Hermes visited a thousand homes seeking shelter and rest but were repeatedly spurned, their true identities being concealed. It was not until they came to the home of Philemon and Baucis that they found hospitality. The old couple welcomed the two visitors, fed them well, and prepared for them a place to rest. Not knowing that they were entertaining gods ‘in the guise of human beings,’ the old couple finally learned the identity of their heavenly visitors. The gods then led Philemon and Baucis to the top of a hill and mercifully spared them from a devastating flood sent in judgment on the inhospitable inhabitants of the region. Their humble home was miraculously transformed into a marble temple. If this local legend was known to the inhabitants of Lystra, it may help to explain their identification of the missionaries as Zeus and Hermes and their eagerness to honor them.

In Lystra, the priest of Zeus prepares oxen for a sacrifice to the two gods in their midst. Up to this point, Paul and Barnabas do not understand what is going on because the people of Lystra are speaking in the local Lycaonian language. Finally, someone translates, in Greek presumably, what is happening. Paul and Barnabas tear their clothes to communicate, in traditional Jewish fashion, their extreme distress at the Lystrans’ attempt to worship them and sacrifice to them.

Paul and Barnabas cry out to the crowd that they are mortal humans, not gods. Paul then launches into his first recorded sermon to Gentiles. Since the crowd consists of Gentiles, Paul does not cite biblical passages to build his case for Jesus. Instead, he appeals to what theologians call general revelation. General revelation is the evidence God provides of His existence in the natural world. General revelation is what we humans can observe without any supernatural aid.

Note what Paul says in verses 15-17:

You should turn from these vain things to a living God, who made the heaven and the earth and the sea and all that is in them. In past generations he allowed all the nations to walk in their own ways. Yet he did not leave himself without witness, for he did good by giving you rains from heaven and fruitful seasons, satisfying your hearts with food and gladness.

Paul appeals to the existence of the heavens (everything that could be seen in the sky), the earth (observable land), and the sea (all of the observable bodies of water). In addition, Paul appeals to the fact that a living God must be sustaining the world because He continually provides rain and plentiful food which bring human gladness.

John Polhill, in [amazon_textlink asin=’B003TO6F76′ text=’vol. 26, Acts, The New American Commentary‘ template=’ProductLink’ store=’toughquest_plugin-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’ddb4aa76-7d06-11e7-b9ee-213517548f74′], writes that God

“had revealed himself in his works of natural providence. This was Paul’s final point (v. 17). God had been sending rain from heaven and causing the crops to flourish. Fruitful harvests had brought plenty of food to nourish the body and cheer the soul. Such ideas of divine providence would not have been strange to the ears of the Lystrans. They were often expressed by pagan writers in speaking of the benevolence of the gods. What was new to them was Paul’s message of the one God—that all the benevolence of nature came from the one and only God who was himself the source of all creation.”

Paul specifically says in verse 16 that God did not supernaturally communicate with the non-Jewish nations in the past. Clinton Arnold explains:

Throughout the history of Israel, God directly and repeatedly intervened by revealing himself to them, making them his own people, redeeming them from slavery, guiding and leading them, bestowing on them his law, speaking to them through the prophets, and giving them promises of a bright future. God did not respond to the Gentile nations in the same way, but he did not leave them without a witness. Paul’s comments here echo what he says elsewhere to the Greeks on the Areopagus (17:30) and to the Romans in his letter (Rom. 1:28).

After they present the gospel message and avert the crisis, some weeks or months go by. Luke records that antagonistic Jews from Iconium and Antioch make their way to Lystra and turn the people against Paul and Barnabas. They stone Paul and drag him outside of the city, leaving him for dead. God, however, miraculously intervenes and saves Paul’s life. His Lystran disciples find him alive. He and Barnabas leave Lystra the next day and proceed to Derbe (see map above).

The missionaries convert many people in Derbe with the gospel message, and then decide to revisit the Christian communities they established in Lystra, Iconium, and Pisidian Antioch. Risking their lives by returning to these places, they encourage and strengthen the faith of the believers. They also appoint elders in each community to lead the church after Paul and Barnabas leave. John Polhill comments that

Derbe was the easternmost church established on the mission of Paul and Barnabas. Had the two chosen to do so, they could have continued southeast from Derbe on through the Cilician gates the 150 miles or so to Paul’s hometown of Tarsus and from there back to Syrian Antioch. It would have been the easiest route home by far. They chose, however, to retrace their footsteps and revisit all the congregations that had been established in the course of the mission. In so doing they gave an important lesson on the necessity of follow-up and nurture for any evangelistic effort. Paul would again visit these same congregations on his next mission (16:1–6).