The Book of Ezekiel was written by the prophet of that name who was born around the year 623 BC and lived until at least 571 BC. The date of his death is uncertain.

Ezekiel was born into a priestly family and lived in Jerusalem until the year 597 BC. This was the year that King Nebuchadnezzar attacked Judah a second time and carried much of the nobility, including Ezekiel, to Babylon.

Peter C. Craigie, in Ezekiel, The Daily Study Bible Series, writes that

Ezekiel belonged to a community established at a place called Tel Abib, by the ‘River’ Chebar, which was actually an irrigation canal, drawing waters from the River Euphrates near the city of Babylon itself. The exiles built for themselves houses with mud bricks and settled there in a strange environment, not too far from the extraordinary capital city of the Emperor Nebuchadnezzar. It was in his fifth year as an exile in Tel Abib that Ezekiel had a profound religious experience. He was thirty years old at the time; if he had still been living in Jerusalem, it was the age at which he would have assumed the full responsibilities of priesthood. But instead he was called to the task of a prophet, of being a spokesman for God. For more than twenty years, he served as a prophet among the exiles. The last of his prophecies that can be dated with any certainty was given in 571 B.C., when he was in late middle-age.

Ezekiel received the first of a series of 14 visions in 593 BC, seven years before Jerusalem would be completely destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar. His ministry was aimed at the Jewish exile community both before and after the fall of Jerusalem. All forty-eight chapters of his book are arranged chronologically and his visions are dated.

Craigie summarizes the overall message of the Book of Ezekiel:

The Jews of his time were faced with an enormous question; to put it in modern words, had their religion come to an end? Phrased so bluntly, it may sound foolish, especially with our knowledge of later history. Yet it was a real and awesome question at the time. The religion of the Hebrews had been linked intimately, before Ezekiel’s time, to the existence of the state of Israel and the possession of the promised land. And yet those two foundations upon which the faith had been established were crumbling before their very eyes. Had their failure, and that of their ancestors, been so terrible that God had finally given up on his people? In such an age, and to such questions, the message of Ezekiel was particularly powerful. He spoke of doom and judgment, but ultimately his faith and message outstripped the reality of contemporary experience. Ultimately, there was hope. Even the disasters of those decades somehow had a purpose in God’s plan. The events would somehow conspire to declare to the people that God was indeed the Lord. And so the final impression that is left after reading this extraordinary book is one of hope. It is not an unqualified and naive hope, but it is real nevertheless.

Chapters 8-11 contain the second of Ezekiel’s visions while he is living in exile in Babylon. The date is September 17, 592 BC. Recall that 592 BC is after the second deportation of Jerusalem, but before the final deportation and destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BC. The exile community is still hoping that God will save Judah and Jerusalem from Babylon, and they are seeking Ezekiel’s word on the matter.

Ezekiel is transported, in a vision, to the temple in Jerusalem by God Himself. God intends to show Ezekiel, and thus the leaders in the exile community, why He will not save Jerusalem. God will show Ezekiel four examples of the idolatrous worship taking place on the grounds of the temple itself.

As seen in the figure above, there were two courts of the temple, the inner and outer. What cannot be seen is that there are gates leading from the outer court to the inner court on the north (top), south (bottom), and east (right) sides of the complex. There was no gate on the west (left) side.

Ezekiel is first transported to the north gate and he sees what is called the “image of jealousy.” It is clear this is an idol of some kind, and many scholars believe it is an Asherah pole. Asherah is the Canaanite goddess of love and was considered to the mistress or consort of El, the highest god in the Canaanite pantheon. This idol is set up right near the northern gate in the temple complex, side by side with the glory of God (the temple symbolizes God’s earthly dwelling).

In verses 7-13, God leads Ezekiel to a secret room that was built on the temple grounds where seventy elders of Israel are worshiping Egyptian gods that are painted on the wall. These are supposed to be the leaders of Israel and they are hiding away in a room to conduct their own form of blasphemous idol worship. They believe that God has forsaken the land and thus cannot see them.

Peter C. Craigie aptly writes:

The elders suffered from the delusion of secrecy. They thought they could act without being seen, and though primarily their secrecy was directed towards their people, at a deeper level it was an attempt to remain secret from God. Yet Ezekiel is standing there, and God is with him, observing the action.

There are no secrets from God. To act as if there were is the height of folly. For human life is conducted on a stage like the interrogation room of a modern police department; the insiders cannot see out, but the observers can see and hear all that goes on inside the room. All speech and behavior should be conducted with an awareness that ultimately there are no secrets from God.

God then moves Ezekiel back to the north gate and there Ezekiel witnesses a group of women worshiping the god Tammuz. Charles H. Dyer explains in The Bible Knowledge Commentary that

‘Tammuz’ is the Hebrew form of the name of the Sumerian god Dumuzi, the deity of spring vegetation. The apparent death of all vegetation in the Middle East during the hot, dry summer months was explained in mythology as caused by Tammuz’s death and descent into the underworld. During that time his followers would weep, mourning his death. In the spring Tammuz would emerge victoriously from the underworld and bring with him the life-giving rains. The worship of Tammuz also involved fertility rites.

The fourth and final example given to Ezekiel involves twenty-five Levitical priests in the inner courtyard facing toward the east and worshiping the sun. Note that facing toward the east means that their backs were toward the temple. They had figuratively and literally turned their backs on God.

Craigie explains the totality of the idol worship witnessed by Ezekiel.

The four scenes with which this great vision begins, taken together, form a comprehensive condemnation of Israel’s worship. All were involved, with no exceptions. The idol of Asherah at the north gate indicated the popular worship of the people. The secret room of sacrilegious murals demonstrated the distinctive failure of the nation’s leaders, the elders. The weeping women illustrated the loss of faith in the Living God. And, in the midst of it all, even the priests were turning backwards in their misdirected attempts at worship. And not only were all the people engaged in this folly; they were without discrimination in their choice of idols. The idol of Asherah represented the religion of Canaan; the secret murals were drawn from the religion of Egypt. The weeping women turned to a god of Babylon, while the priests worshipped the sun, whose cult was practised in almost every nation of the ancient Near East.

After showing Ezekiel the abominations in the temple complex, God says,

Have you seen this, O son of man? Is it too light a thing for the house of Judah to commit the abominations that they commit here, that they should fill the land with violence and provoke me still further to anger? Behold, they put the branch to their nose. Therefore I will act in wrath. My eye will not spare, nor will I have pity. And though they cry in my ears with a loud voice, I will not hear them.

In chapter nine, Ezekiel witnesses the destruction of the people of Jerusalem by God. All who have turned against Him are executed. This vision is a foreshadowing of the Babylonian attack in 586 BC.

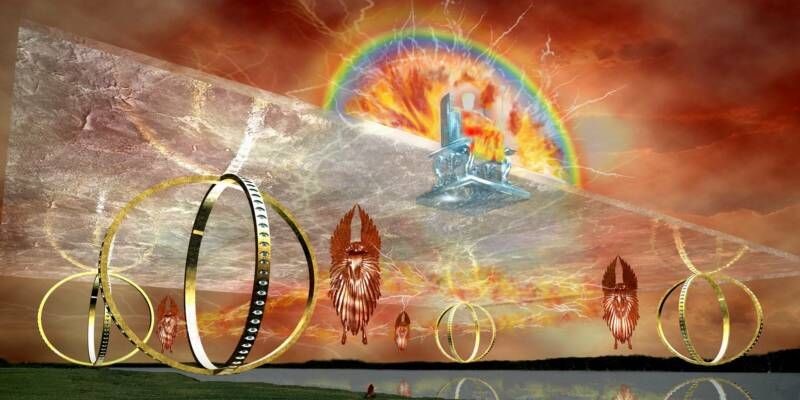

Chapters ten and eleven report the most devastating consequence of Judah’s betrayal: God’s glory leaves the temple of Jerusalem. Ezekiel sees God mount what looks like a chariot. The chariot is composed of a throne sitting on a large platform. Underneath the platform are four cherubim and four double-wheels. The cherubim and the wheels move the chariot wherever God wills. See the figure below.

God summons a man dressed in white linen to come to the cherubim under the chariot and receive burning coals from them. The burning coals are to be scattered around the city of Jerusalem. Lamar Eugene Cooper, in vol. 17, Ezekiel, The New American Commentary, writes,

Some see this as a rite of purification; others see it as an act of judgment. Both ideas are appropriate. Judgment from God is redemptive in its purpose, not purely punitive. His ultimate goal was the restoration of the nation through a purified remnant.

God moves, on the chariot, from the interior of the temple to the eastern gate of the inner courtyard. The eastern gate faces out over the Valley of Kidron. On the other side of the valley is the Mount of Olives. God lingers at the eastern gate, as if He is giving Jerusalem one last chance to repent.

Finally, in chapter 11, verses 22-25, God rises up from the eastern gate and exits the city. His chariot transports Him to the Mount of Olives, where He makes his final departure from the temple and Jerusalem. Cooper writes:

The departure of the glory of God from the Mount of Olives was the final step in the judgment process. The removal of his blessing signaled the end of his longsuffering with a disobedient and rebellious people. God had exhausted every means of soliciting repentance from the people. Therefore he removed the glory that was the sign of his presence so that judgment might run its full course. The absence of the glory signaled the last stage in the process of reprobation of the self-willed people of the nation.

Ezekiel reported everything he saw to the elders in exile. What were they to do with this information? What hope was left? Craigie explains that hope now rested with the exile community. The residents of Jerusalem had been completely rejected by God.

And so it was upon the exiles that the future now depended. Thinking themselves to be useless, they had looked to others in far off Jerusalem to provide a source of hope. But the tables were being turned. If there was hope to be found, it lay within them, not in the empty hands of others far away. The citizens of Jerusalem had already written off the exiles as irrelevant to the future of their city. Indeed, the exiles themselves thought that there was nothing they could do. But now they were learning that the weak of this world were the ones through whom God would work. And such new hope was not without its attendant anxiety, for it involved awesome responsibility.

Yet the message of the prophet to his fellow exiles carried with it a potent promise, to be developed still further later in his ministry. The future now lay with those in exile, yet it was plain for all to see that they did not have in themselves the strength to undertake the task. The enabling power would be provided by God in the gift of a new spirit and a new heart (see further 36:26). The doomed citizens of the city had built by themselves, and their buildings would soon come toppling down. The exiles, in their mission, would have to learn to build in a new way, employing the strength coming from their new and God-given heart and spirit.