Chapter 13 begins with an ominous declaration: Amnon loves Tamar. Amnon is David’s firstborn son and heir to David’s throne. His mother is Ahinoam. Tamar is the daughter of David and Maacah. Maacah and David also have a son named Absalom, so Absalom and Tamar are brother and sister. Tamar is Amnon’s half-sister.

Chapter 13 begins with an ominous declaration: Amnon loves Tamar. Amnon is David’s firstborn son and heir to David’s throne. His mother is Ahinoam. Tamar is the daughter of David and Maacah. Maacah and David also have a son named Absalom, so Absalom and Tamar are brother and sister. Tamar is Amnon’s half-sister.

Amnon wants to have sexual relations with Tamar, but she is still a virgin and yet to be married. In addition, the Law specifically prohibits sex/marriage between half brothers and sisters. Amnon, however, doesn’t care about the Law and wants Tamar anyway.

Jonadab, Amnon’s cousin, suggests a plan for Amnon to be alone with Tamar. He is to pretend he is sick and request that Tamar come to his house to prepare food for him. When Tamar prepares bread for him, he orders everyone else out of the house. When she is alone with Tamar in his bedroom, he asks her to have sex with him.

Tamar, as a woman who knows the Law, refuses his advances. She knows that sex between brother and sister is forbidden, and she also knows that if she loses her virginity to Amnon, she will likely never marry. Her only option is to tell Amnon that he should petition King David to allow them to marry. Amnon is not interested in marriage, so he rapes her.

Once the deed is done, he kicks her out of his house and refuses, again, to marry her. In fact, verse 15 says that he hates her after they had sex more than he loved her before they had sex. We know, for sure, that Amnon simply lusted after her. There was no love involved.

Tamar tears her ornamented robe, which marked as her one of the virgin daughters of the king. There is no hiding what was done, as Tamar publicly mourns the loss of her virginity. Her full brother Absalom finds out what happened and takes her into his home. No man will want to marry her now. Absalom hates Amnon for what he has done, but he never tells him. David also finds out what happened and he is furious, but he does nothing about it.

Dale Ralph Davis, in 2 Samuel: Out of Every Adversity (Focus on the Bible Commentaries), faults David for his inaction:

It should have led to a righteous result. His anger should have led to justice. Amnon should have been punished and Tamar exonerated. Instead Amnon is not held accountable, Tamar receives no redress, and Absalom is handed a plausible excuse for revenge. David heard. He was very angry. And he did nothing.

Two years later, Absalom hosts a party at a place called Baal Hazor centered on the shearing of his sheep. He requests that David join him for the festivities, but David declines. Since David will not come, Absalom requests that Amnon come in his place, since the firstborn could represent his father. David agrees.

In verse 28, Absalom instructs his men to kill Amnon once he’s drunk, and this is exactly what they do. After two years of plotting revenge, Absalom acts and kills his half-brother, the heir to the throne.

Absalom flees to his maternal grandfather’s home in Geshur. He stays there for three years until David finally summons him to come back to Jerusalem. When he returns to Jerusalem, David refuses to see him for 2 more years. At the prompting of his trusted general Joab, David allows Absalom to come before him and they are reconciled. It had been 5 years since the murder of Amnon.

Not content with his circumstances, and perhaps still angry at his father for not punishing Amnon himself, Absalom begins to build a political following in Israel. He acquires a chariot with horses (the transportation favored by Canaanite royalty) and an entourage of 50 soldiers that would run ahead of the chariot. These are the trappings of royalty and power which support the image he wants to convey to the people of Israel.

Robert Bergen, in 1, 2 Samuel: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture (The New American Commentary), also notes:

The biblical narratives stretching from Exodus through this point in 2 Samuel are surprisingly negative in their portrayal of horses and chariots. The texts consistently depict only enemies of the Lord and his covenant people as having them. The Egyptians (cf. Exod 14:9–15:21; Deut 11:4; Josh 24:6), northern Canaanites (Josh 11:4–9; Judg 4:15; 5:19–22), and Arameans (8:4; 10:18) all used them unsuccessfully in battle against Israel. Thus, when Absalom linked them with himself, he was joining his ambitions with symbols of hostility against the Lord and Israel, and with ultimate failure.

Absalom also intercepts numerous Israelites at the gate of Jerusalem who are seeking judicial rulings from David. He lies to them, saying that David is not fulfilling his role as judge in Israel. Absalom suggests that he is perfectly willing to serve in this capacity. He also flatters the supplicants by always agreeing that their case is just.

After 4 years of Absalom’s campaigning at the gate, he is ready to make his move. He asks David for permission to travel to Hebron to make a sacrifice to God for allowing him to come back to Jerusalem from exile. David agrees to his request. Why did Absalom really want to go to Hebron? Robert Bergen explains:

At Hebron Absalom found himself twenty miles away from his father and protected by strong walls. From this relatively safe base of operations Absalom moved quickly to usurp David’s throne. He prepared for the public phase of his plot by sending secret messengers throughout the tribes of Israel (v. 10) to make a coordinated proclamation throughout the land. Once in place, they were to await ‘the sound of trumpets’ and then announce simultaneously that ‘Absalom is king in Hebron.’ Implicit in this proclamation was a call to arms for those who supported Absalom in his efforts.

Absalom also brings along 200 men from David’s administration to Hebron, letting them think they are guests at his sacrifice. This was a brilliant move by Absalom, depriving his father of 200 of his friends and advisors during the impending crisis. They would be forced to help Absalom or be killed. While in Hebron, Absalom also sends for one of David’s top advisors, Ahithophel. Recall that Ahithophel is the grandfather of Bathsheba, the woman who David seduced. It is quite possible that Ahithophel still harbors a hatred for David for what he did to Bathsheba and Uriah.

If there was any question whether Absalom would succeed in his coup, David receives a messenger in Jerusalem who gives him the horrible news: “The hearts of the men of Israel are with Absalom.”

Since there is not enough time to comment on all the events of chapters 15-17, here is a brief synopsis. David flees Jerusalem with his family, officials, and a small army of soldiers. He leaves behind 10 concubines to tend to operation of the royal palace while he is gone. He also leaves behind spies to inform him of Absalom’s plans.

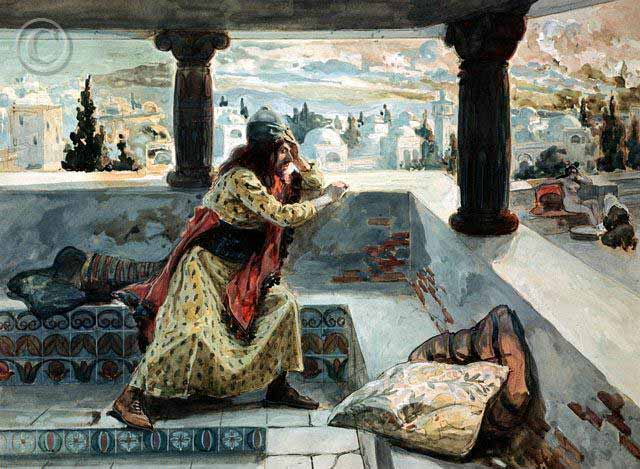

Absalom moves into David’s palace and has sexual relations with the 10 concubines on the roof of the palace to publicly declare himself as king of Israel. After consulting two advisors, Ahithophel and Hushai (a spy for David), he gathers a large military force and leads them to kill David and defeat his army, who have crossed over to the east side of the Jordan River. David’s spies warn him of Absalom’s plans.

At the beginning of chapter 18, David divides his army into 3 groups, each commanded by one of his generals. The plan is to fight Absalom in the surrounding forests, where David’s forces will have a military advantage. David wants to go to battle, but his generals convince to stay behind. Before they leave, David commands the soldiers to be gentle with Absalom if they capture him. David, evidently, wants to be reconciled with him again.

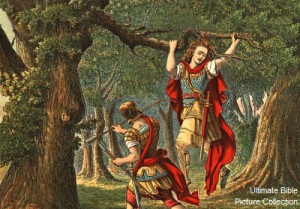

In verses 6-8, we learn that David’s army defeats Absalom’s army. Some 20,000 soldiers die. Absalom’s fate is described in verses 9-15. As he is riding his mule, he gets stuck in low-hanging tree branches and is left hanging from the tree, still alive. Some of David’s soldiers spot him and tell Joab, David’s top general.

Joab asks the soldiers why they didn’t kill Absalom and they cite David’s instructions to be gentle with him. Joab takes matters into his own hands and he kills Absalom himself by plunging three javelins into him. Thus ends the rebellion of David’s son Absalom.

What can we learn from this whole sordid affair? First, God’s prophetic words always come true. The prophet Nathan warned David that blood would not leave his house, and that a family member would sleep with his wives, thus rebelling against David. All of this came to pass with Absalom.

Second, the sins of parents are passed on to their children. Just as David illicitly slept with Bathsheba, Amnon had illicit relations with Tamar. Just as David has Uriah murdered, Absalom had Amnon murdered.

Third, note that Absalom never consulted God or his prophets. He only sought advice from men, none of whom had a word from God. This behavior mirrored that of the kings of the Canaanite nations. What a contrast with David! Robert Bergan draws out the contrast:

At every crux in his life, David sought the word of the Lord, either through an Aaronic priest (1 Sam 23:1–6; 2 Sam 5:19, 23) or a prophet (7:3–17). Absalom’s pursuit of and compliance with human counsel brought about the hasty end of his regime. David’s pursuit of and obedience to divine revelation brought him only success and dynastic blessings. By providing contrasting narrative portraits of these two Davidic kings, the author writes a prescription for the success of all future leaders in Israel: seek the word of the Lord through its authorized mediators and obey it.

Fourth, Absalom’s death carries theological significance. Bergen writes:

The words used by the soldier to report Absalom’s condition are of great theological and thematic significance: ‘Absalom was hanging [Hb., tālûy] in an oak tree.’ The word translated ‘hanging’ here is used only once in the Torah (Deut 21:23) to declare that ‘anyone who is hung [tālûy] on a tree is under God’s curse.’ Absalom had rebelled against divine law by rebelling against his father (cf. Exod 20:12; Deut 5:16; 21:18–21) and sleeping with members of David’s harem (Lev 20:11). Absalom had the massive armies of Israel fighting to protect him, and he was personally equipped with a fast means of escape not afforded other soldiers—a mule. Nevertheless, in spite of these seemingly insurmountable advantages, Absalom could not escape God’s judgment. The Lord had declared in the Torah that one who dishonored his father was cursed (Deut 27:16) and likewise that one who slept with his father’s wife was cursed (Deut 27:20)—Absalom, of course, had done both. Although no army had been able to catch Absalom and punish him, God himself had sent a curse against him that simultaneously caught and punished the rebel. The fearful judgments of the Torah had proven credible: the Lord had upheld his law.

Philosopher Ed Feser

Philosopher Ed Feser  In previous chapters, Israel has been at war with the Ammonites, but they have not yet completely defeated them. As chapter 11 begins, David sends the army to finish off the Ammonites once and for all. They have retreated to a city named Rabbah, so David’s forces are besieging Rabbah.

In previous chapters, Israel has been at war with the Ammonites, but they have not yet completely defeated them. As chapter 11 begins, David sends the army to finish off the Ammonites once and for all. They have retreated to a city named Rabbah, so David’s forces are besieging Rabbah. In 2 Samuel 7, verses 11-14, God speaks to the prophet Nathan about King David:

In 2 Samuel 7, verses 11-14, God speaks to the prophet Nathan about King David: Some time after David has placed the ark in Jerusalem, a palace has been built for him, and he has a period of rest from his enemies, he decides that he should build a temple to house the ark (God’s home on earth). David communicates his plans to Nathan, the prophet, and Nathan affirms his plans. However, that night Nathan hears from God about His plans for David, and they are not at all what Nathan expects!

Some time after David has placed the ark in Jerusalem, a palace has been built for him, and he has a period of rest from his enemies, he decides that he should build a temple to house the ark (God’s home on earth). David communicates his plans to Nathan, the prophet, and Nathan affirms his plans. However, that night Nathan hears from God about His plans for David, and they are not at all what Nathan expects! As we continue to look at computer simulations of Darwinian evolution, we come to our second major problem: even with intelligent intervention by the programmers of these simulations, they mostly fail to produce irreducibly complex systems. J. Warner Wallace resumes his analysis in

As we continue to look at computer simulations of Darwinian evolution, we come to our second major problem: even with intelligent intervention by the programmers of these simulations, they mostly fail to produce irreducibly complex systems. J. Warner Wallace resumes his analysis in