Post Author: Bill Pratt

This seems to be a common misconception, one that I have seen many times on the blog. Recently, one of the most helpful commenters on the TQA blog, Walt Tucker, wrote a detailed response to this claim as a comment on another post. He has given me permission to share his commentary in this blog post. Every word below is Walt’s unless I indicate otherwise, and I thank him for giving me permission to use his excellent response.

A friend of mine was using his apologetics know-how with an atheist and using principles that are self-evident in nature, such as the law of non-contradiction, to argue for the existence of God. The atheist claimed that quantum superposition violates the law of non-contradiction and thus my friend’s whole argument was null and void. Knowing that I have knowledge in quantum theory and apologetics, my friend asked whether quantum superposition does violate the law of non-contradiction.

Since this comes up so often with skeptics and atheists who try to use arguments from quantum mechanics against the classical apologetic argument for the existence, or at least the certainty of the existence, of God, I thought I would post my reply to my friend here for all of my Christian friends to use who might come across a person who tries to use the ill-fated quantum approach against God. (Of course God created the quantum world, so it isn’t so likely that such arguments can be used against His existence. Such attempts show either a misunderstanding of the nature of God, or a misunderstanding of nature itself.)

Before I present the reply, I need to give some background on how the argument the atheist is using arises in quantum mechanics. There is a classic experiment used to demonstrate the non-intuitive nature of the quantum world. It is called the two-slit experiment. Light is made up of discrete packets of energy called “quanta.” You can never have a half, or any fraction of, a quanta. In one sense, it is like having a gum ball from a gum ball machine. You get a whole gum ball. You can smash it, chew it, or whatever, but you still have the same about of gum and it only comes in whole gum balls.

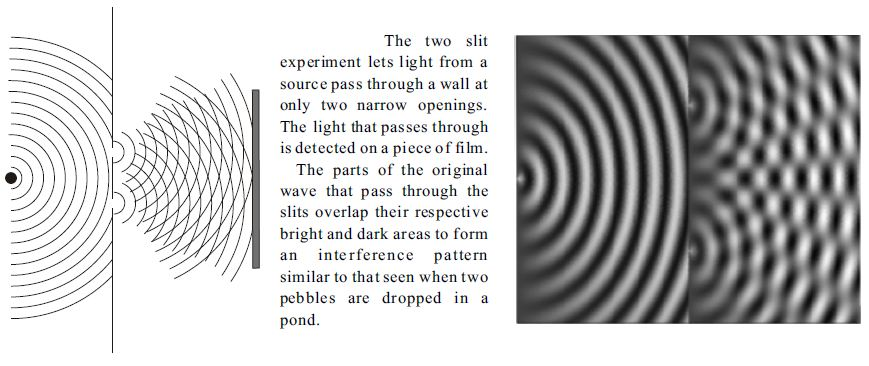

So, light is generated from atoms and absorbed by other atoms as quanta packets of energy (called a photon). The light we see in a room with a typical incandescent light bulb is many millions of quanta, so one quanta of photon energy is very, very small. In the experiment, a single quanta of light is shot towards the double slit (see figure below).

There is a piece of film on the other side. When both slits are open, the light appears to go through one of the two slits and be absorbed by the film at one point at a random position. But when this is done over millions of shots, the image on the film is an interference pattern as if the photons went through both slits at the same time (the image on the film is the classical wave interference pattern of light). An interference pattern is the crossing pattern you see when you drop two pebbles in a pond as the same time and the waves interfere – high crests and low crests – with light it is bright and dark areas.

But since only one photon is shot at a time, it is odd that the film shows an interference pattern when intuition would say a particle of light, the photon, would only go through one slit or the other, but couldn’t go through both. To test that, one can put a detector at the slits to try and see if the photon goes through one slit or the other, or both. When that is done, the photons are detected at only one slit or the other, randomly, and the interference pattern on the film disappears (it is what you would expect if the photons did go through only one slit or the other).

So, knowing which slit the photon goes through destroys the interference that appears on the film that would appear when you don’t know which slit the photon goes through. Quantum mechanics is a mathematical formulation of this behavior for predicting the outcome of experiments called observations. Each detection on the film would be an observation. As such, what is called an observation does not require a human observer, but does require some sort of detector, whether it be a film, a photo-detector, or anything that could absorb the photon. Now knowing the weird behavior of the quantum world, I give the reply to the question.

[Bill Pratt] In part 2 of this series, Walt completes his explanation as to why quantum mechanics does not violate the law of non-contradiction.